‘This coup is a coup against the Indian, it is a coup against our process of change organised by the North American empire, not just by the Bolivian right (…) Argentina has lithium reserves, Chile as well; how nice would it be for the three South American countries to industrialise our lithium, as a people and as a state. From here we can decide the price of lithium for everyone.’ So said Evo Morales at a rally in Buenos Aires in January this year.

Morales was in exile in Argentina, having been removed from power on 10 November 2019 in what he claims was a US-backed military coup. He had been accused of rigging the 2019 elections, with the results being called into question in an audit by the Organisation of American States (OAS). But numerous studies, including by the Center for Economic and Policy Research, rejected the OAS findings and were backed up by a letter signed by 116 economists from around the world demanding that OAS withdraw unfounded accusations which were contributing to political unrest and human rights violations.

However, Morales was forced to flee, first seeking refuge in Mexico and then Argentina, where he resided for almost a year. He returned to Bolivia in November.

Geopolitics of energy transition

While much discussion at the time was devoted to the legitimacy of the elections and the legality of Morales’ removal, last year’s coup in Bolivia was about much more than this, feeding into a larger geopolitical dispute over access to natural resources.

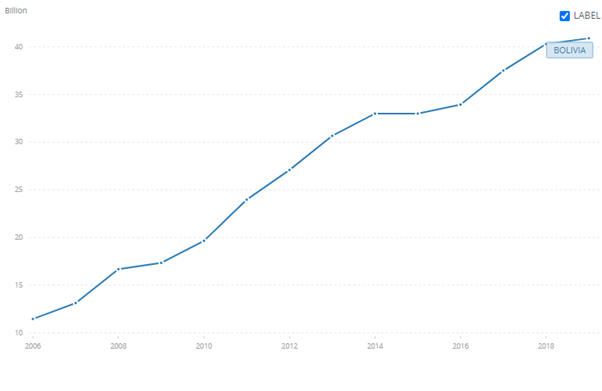

One of the principal objectives of Morales’s government was restoration of Bolivian sovereignty over natural resources. During his 14 years in power he brought a whole range of enterprises under state control, including not only extractive industries such as the natural gas sector and mining, but also utilities and strategic industries like water, electricity, aerospace and others. Coinciding with a period of boom for many of Bolivia’s main exports, not only did national GDP increase, but much revenue was invested in social policies that targeted the poor. During Morales’ time in power, poverty decreased from 60.6 per cent to 34.6 per cent and extreme poverty from 38.2 per cent to 15.2 per cent.

One of the foundations for his plan for further economic growth was development of a ‘100 per cent national’ lithium industry. Lithium is an ultra-light metal which allows storage of a large amount of energy in a very small space. It is contained in the batteries of smartphones, laptops and electric vehicles, and is an essential component of clean energy storage technologies. As the world strives towards a more sustainable future, the World Bank estimates that demand for key metals is expected to grow about 450 per cent by 2050, with lithium central to the move away from fossil fuels to renewable sources of energy.

Morales considers lithium a strategic resource with the potential to break Bolivia’s dependency on the northern hemisphere. In his vision, Bolivia could become one of the main players in the emerging clean energy market – ‘the Saudi Arabia of lithium’ – with a lithium industry under national control lifting the country out of poverty and strengthening its position in the global political order. Luis Arce, Morales’ former finance minister, now president of Bolivia following a landslide victory in fresh elections in October, affirmed that the lithium industry could generate $4.5 billion annually[TG1] , as well as 41 new industries and 1,300 new jobs. This includes development of the entire supply chain and the export of lithium not merely as a raw material, but as a processed commodity.

But this nationalistic approach to resources governance has made Morales a target for those excluded from the business. For Morales, ‘The problem began when the United States was left out.’ ‘When we say that natural resources belong to the people – this is where military bases come, this is where military interventions come, even the coup.’ he said in an interview with TeleSur.

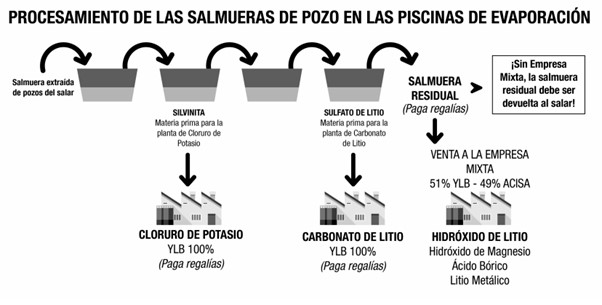

However, Bolivia lacks the experience, funds and expertise to go it alone. It had to seek a foreign partnership, with the auction won by ACI Systems Alemania (ACISA), a German company operating in the fields of energy, mobility, raw materials and production; among its main customers are companies like Tesla, BMW and IBM. In December 2018, Morales issued a decree (3738) authorizing a joint venture between the state-owned Yacimientos de Litio Bolivianos (YLB) and ACISA. The company promised to invest $1.3 billion for a 49 per cent stake, with the rest belonging to the Bolivian state. The contract, which was to last for 70 years, permitted production of lithium hydroxide and cathode materials (hydrated cobalt, nickel and manganese sulphates and iron phosphate of very high purity), then the cells and ultimately lithium ion batteries themselves.

The agreement caused a series of protests in the department of Potosí, with the Potosí Civic Committee (COMCIPO) organising a hunger strike to demand an increase in mining royalties for local communities from the exploitation of the Salar de Uyuni salt flats, from 3 to 11 per cent. COMCIPIO called for dissolution of the decree, arguing that Morales was surrendering Bolivia’s natural resources to transnationals. The Ministry of Energy responded to all the accusations in an official letter, emphasising that ACISA did not have any control over Bolivian natural resources. Lithium as a raw material was to be extracted solely by the state company YLB, before being sold to the mixed company YLB-ACI and then processed and exported.

But eventually Morales bowed to pressure and terminated the partnership with ACISA on 3 November last year. However, this did little to satisfy the protesters, who joined the opposition in demanding Morales’ resignation. A week later, he was overthrown in a military coup.

‘We will coup whoever we want’

The OAS audit clearly indicates the involvement of United States in the coup. Although the organization was created to facilitate Interamerican diplomacy and promote peace, democracy and economic cooperation, it has been often used as a tool of destabilization in the region (for example, in the 2009 coup in Honduras and the 2011 elections in Haiti). The headquarters of the OAS are located in Washington and about 60 per cent of its funding comes from the American government. The Trump administration was a major cheerleader of the coup in Bolivia: ‘The resignation yesterday of Bolivian President Evo Morales is a significant moment for democracy in the Western Hemisphere (…) The United States applauds the Bolivian people for demanding freedom and the Bolivian military for abiding by its oath to protect not just a single person, but Bolivia’s constitution.’

Then on 24 July, Elon Musk, the CEO of American electric car producer Tesla, publicly admitted in a now-deleted tweet that the lithium had been the reason. ‘We will coup whoever we want! Deal with it.’ Musk wrote.

Musk’s tweet did not go unnoticed by Morales. ‘The owner of Tesla claims to have financed the coup, entirely because of lithium. In the United States there is great concern about lithium, and this coup is for lithium. They do not want us to give the added value to lithium as a state, they always want our natural resources to be in the hands of transnationals,’ he said.

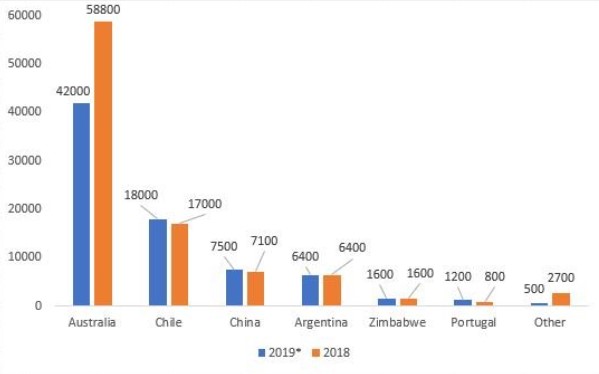

Aside from being a global electric vehicle producer, Tesla is also concerned with energy generation and storage technologies and lithium is an essential component of both. While Musk’s subsequent claim that Tesla’s lithium comes from Australia may well be true, Bolivian lithium reserves surpass Australia’s more than threefold and Tesla will surely be looking to diversity its supply chain as the global energy transition progresses. After the coup, Tesla stocks increased astronomically.

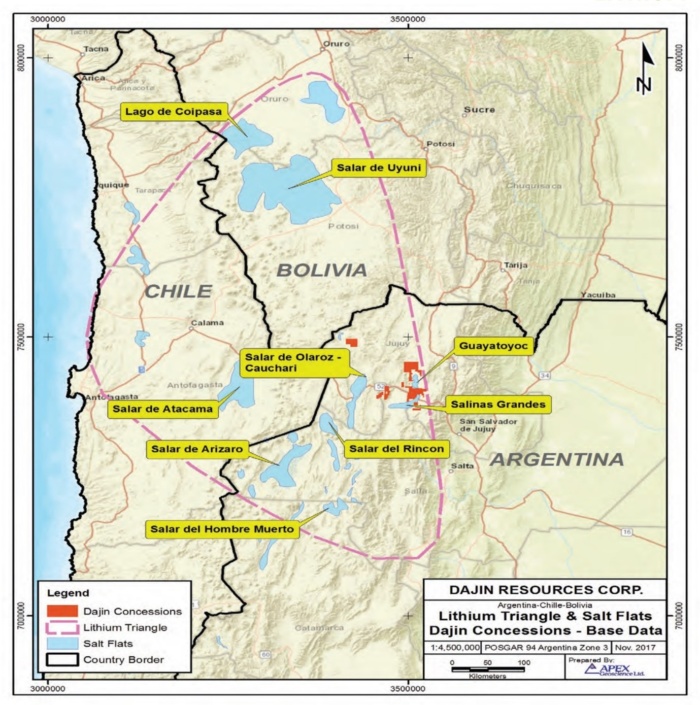

Almost 85 per cent of the world’s lithium reserves are concentrated in a region known as the Lithium Triangle – along the borderlands of Bolivia, Argentina and Chile. Chile and Argentina are both amongst the world’s largest producers: in 2019 Chile produced 18,000 tonnes of the mineral and Argentina 6,400. But with 21 million metric tons of the mineral – about 30 per cent of world’s total resources – Bolivia’s deposits are even greater.

However, Bolivia’s resources remain largely unexploited because the process of extraction is more complicated than in its neighbouring countries. The Salar de Uyuni is located 3,650 meters above sea level, meaning that the climate is cooler and precipitation levels much higher. This hampers evaporation systems, which depend on a large amount of sun. Bolivian deposits also contain a much higher concentration of magnesium, which is expensive and time consuming to separate. Furthermore, Bolivia’s more nationalistic approach to resource governance has slowed down extraction, compared to Chile and Argentina where the approach has been more liberal and extraction is conducted by transnational companies.

The Future of Bolivian Lithium?

Upon his return to Bolivia in November 2020, Morales gave a press conference in the majestic Palacio de Sal in Uyuni, where he again touched on the lithium issue:

‘The plan that we had we are going to resume now with the President Lucho [Luis Arce] (…) By 2030 we plan to install 41 [lithium] plants, the majority in the department of Potosí and some in the department of Oruro.’

He also mentioned that a few weeks earlier he had had a virtual meeting with the former leaders of Yacimientos de Litio Bolivianos and representatives of the Argentine Ministry of Science and Technology to discuss binational lithium industrialisation. Trans-border resource governance may trigger inter-state rivalry and conflict, but it may also create opportunities for cooperation. A regional approach to lithium would enhance the ability to resist interventions by empires seeking to gain control over resource rich states to obtain an uninterrupted supply of strategic resources.

President Arce also stated his intention to push ahead with the plan for lithium extraction laid out by Morales before his removal:

‘Bolivia has already progressed, today we have potassium chloride and lithium carbonate already in production. Bolivia already produces lithium, what we want is to advance in the production of lithium batteries and for this we are going to enter into partnerships with large companies that guarantee international markets but where most of the business will of course belong to the Bolivian state.’

Considering that very few states have the necessary expertise and technology for battery production – and that Bolivia insists on retaining a majority of any profit – it will not be an easy task. That said, ACISA has expressed its willingness to renew the agreement with Bolivia and President Arce has said the partnership will go ahead provided the company meets certain conditions.

If Bolivia succeeds with resource governance on its own terms, it will be little short of revolutionary. It will irreversibly transform the global geopolitical landscape and power relations which for so long have been shaped by the geographical distribution of fossil fuels and the global energy trade. Evo Morales is sure of his victory; following Donald Trump’s recent defeat in the American presidential elections, Morales claimed that ‘this time the Indian has overthrown the gringo’ – but is this really the end of the battle?

Main image: the Salar Uyuni, Bolivia, site of one of the largest lithium deposits in the world.