Chilean politics are marked by several long-running and highly divisive controversies, many deriving from the most consistently neoliberal economic policies and property arrangements in the world. One of these is the management and control of water resources. Water is unevenly distributed throughout the national territory – scarce in the north of the country and abundant in the south – a problem accentuated by privatisation, drought and climate change.

‘We have a huge water crisis that the government is refusing to address. The crisis is mainly because more than 80 per cent of water is in private hands and is used for industrial production, mining, agriculture and livestock, creating a shortage of drinking water for Chileans as well as contaminating it with industrial waste. Our current constitution determines that water rights belong to the owner, leaving the population as a whole, not to mention the environment, unprotected’. Alexis, political activist from Talca in the Central Valley of Chile.

When water became a commodity, not a right

The Chilean Water Model represents the world’s leading example of the free-market approach to water law and resources management. It treats water not only as private properly, but also as a fully tradeable commodity. If someone owns the water providing irrigation to a farm or farms, the farms have little if any ability to ensure their continued access or to protect themselves against price hikes. The water provider is a monopoly – they cannot go and get the water fron another river.

Water privatisation began in 1981 under General Pinochet’s military dictatorship, a regime characterised by its pursuit of neoliberal economic policies with a determination unknown in any other country. Until then, it was the government’s responsibility to protect and oversee optimal allocation of water resources.

The new Water Model enabled private investors and companies to buy ‘stocks’ in water. Water rights became legally separate from ownership of the land through which the water flowed, and could be freely bought, sold, mortgaged, inherited, and transferred like any other commodity. The return to democracy in 1990 then cleared the way for international firms to buy up the nation’s water utilities and placed farmers and consumers in an even weaker position.

In 1992 the recently elected democratic government attempted to modify the Code in a way that discouraged short term speculative trading of water rights, amongst other improvements, but there was fierce resistance, and the bill was only approved in 2005 after a 13 year delay.

The philosophy behind the 1981 Water Code was to establish permanent and tradable water use rights so as to reach an efficient allocation of the resource. What it did not predict was that the reforms would fundamentally change the way water is valued and managed globally. As Daniel Gallagher described in the Guardian in 2016 – ‘no longer a mere necessity for human survival, water [became] an object of international financial speculation’.

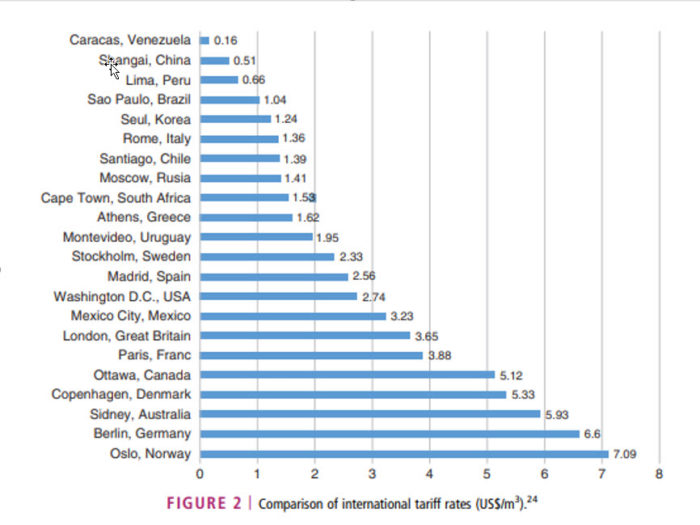

In opposition to this stands the concept recognized in almost every other country that access to water is a basic human right. The high and unregulated tariffs that private water companies can charge are a permanent source of discontent amongst Chileans. For example, Aguas Andinas monopolises Santiago’s water supply and charges one of Latin America’s highest tariffs. The 2005 reforms led to some rights being taken away from companies that were not themselves using the water as an input in production, but rather as a tradeable investment or for bottling. However, the Model contains many other glaring flaws which remain untouched.

The impacts of a neo-liberal model

Privatised water means that once water rights are given to an individual or a company, the State no longer intervenes, and the reallocation of water happens through the water market, where private owners of water rights can rent, buy, or sell them, like any other asset. This has successfully encouraged private investment in the country (particularly the mining industry); in certain cases it has encouraged owners of water rights to improve their efficiency; and allowed the development of hydroelectric power.

Sebastian, an enologist from the Maule region, believes that water should not be a completely public service. Water needs to have some sort of value because if there is no monetary incentive to look after this resource, it gets wasted. Imagine that someone wants to grow alfalfa in the desert region in the north. Alfalfa needs a huge amount of irrigation compared to other crops and therefore such a plan is inefficient. Water that could be used better elsewhere will be wasted. In this sense, the system encourages more efficiency; water goes to people who will use it better.

‘I don’t think [the Chilean water model] is a bad system,’ he says. ‘It needs improvements, but I don’t think water should be a completely public good. I like the way that water is divided into ‘stocks’ because it equally divides the river’s water capacity. One ‘stock’ provides more water when there is more water in the river, and less when the river is drier. As an agriculturalist, this guarantees that I can grow something.’

Unfortunately, none of these advantages is without problems. Mining is controversial for its pollution and because it takes place in areas of high indigenous population in the north, often desecrating lands held sacred by them. In northern and central Chile, there have been confrontations between indigenous communities and mining companies. Smaller businesses and farms producing high-value fruit and vegetables require a lot of water but they lose access (and sometimes their crop) when faced with competition from mining corporations with vastly greater resources.

Furthermore, irrigation efficiency remains low; and the definition of water rights remains vague, incomplete and confusing, meaning that resolving water disputes is very complicated and expensive.

Reform is thwarted

In interviews with the newspaper El Mercurio in January 2020, Fernando Santibañez, professor of agroclimatology at the University of Chile, said that new legislation was needed to enable the state to intervene so as to ensure that human use of water takes priority over the other uses, to remove rights when their owners do not use them for productive purposes over a long period and also to deal with the ‘speculative accumulation of water rights’.

Camila Boettiger, a specialist in regulatory law, said that the current arrangements do not deal adequately with environmental issues, inequalities of access, and difficulties in the management of river basins.

In January 2020 a very longstanding initiative to reform the Constitution so that it would recognize water as a resource ‘the use and control of which belongs to the citizenry as a whole’ was passed by 24 votes to 12 in the Senate, but failed to get the required two thirds majority. Thus a project to reform the Water Code which had been debated on and off in the Congress since 2010 was once again put on hold because it was seen as a threat to private property. The reform is now on ice for at least a year.

Meanwhile the sacrosanct property entitlement makes it difficult for the state to intervene to protect small farmers and consumers because all the water rights in the country are in private hands.

The worry over the environment, particularly, demands attention. However, because environmental issues were not a public or political concern in the 1970s and 80s, the Water Code includes no provision on the subject. With reports that Central Chile – where the majority of the population is concentrated – has received 30% less rainfall than normal over the past decade (in a situation scientists are referring to as a megadrought), there are indications that time is running out.

What is being done to address this?

Because of the supermajorities required for changes to basic legislation like that governing water, designed to armourplate market relations and prevent the state from intervening to regulate them, neither the Chilean Constitution nor the economic model for water can be amended today without the full agreement of the conservative political forces that first implemented them. Furthermore, the political balance has shifted further to the right in recent years and the national economy has weakened since the 1990s, presenting further obstacles There may be a new Constitution in the coming years but it will take several years to write, to negotiate and to be approved.

Residents of Talca and Maule – one of the drought-affected regions in the Central Valley – are sceptical about the chances of obtaining change.

Maria Jose said ‘change is doubtful because [addressing the water crisis] wasn’t a part of the government’s agenda. Political changes that have already been achieved were a product of social uprising. What’s more, the government’s priorities have kept changing during this presidential term.’

Alexis comments: ‘the government is not willing to address the great water crisis that we have today in Chile. The government, through the Minister of Agriculture, defends the rights that companies and private individuals have over water. In fact, Minister Walker himself owns an enormous quantity of water rights. It makes no sense to address an issue which, upon its resolution, would hurt personal business interests.’ Recalling the predominant demand for water from farming, industrial mining, and businesses, he says: ‘Also, campaigns for the rational use and conservation of water are aimed at the civilian population, which uses only 7 per cent of the water, therefore, these campaigns are not effective because they do not have a real impact on water conservation.’

‘I only hope,’ he continues, ‘that, with the plebiscite for the new constitution, the water crisis will be discussed.’

Sebastian, despite his defence of water privatisation, emphasises that because of the environmental impacts ‘it is really quite urgent that the government addresses the model. We need better regulation, especially amongst big companies.’

‘If I could make improvements to the system, I would ensure that there was enough water set aside for public consumption; that there was enough for the maintenance of local wildlife; and that small rural populations received a fair share. Water speculation should also be illegal. I don’t agree with water being a 100 per cent private good, after all, both we and the environment need it to survive, not just to generate profit.’

The next steps?

Many critics say that the current model needs a far stronger challenge than anything yet seen. Until now, Chile has found itself in a stalemate with its water crisis because the Chilean Water Code reflects the constitution under which it was adopted: without priorities to protect the environment and defended by right-wing politics.

However, the plebiscite for a new constitution, now postponed till 25 October, offers new hope. The megadrought has truly highlighted how the system fails the poorest and the environment throughout many regions in Chile. It is an issue that, amongst many others, that the Chilean government cannot ignore.

Jessica Rothwell studied Spanish and Russian at the University of Bath. She has been working as an English language assistant at the University of Talca, Chile.