My presentation

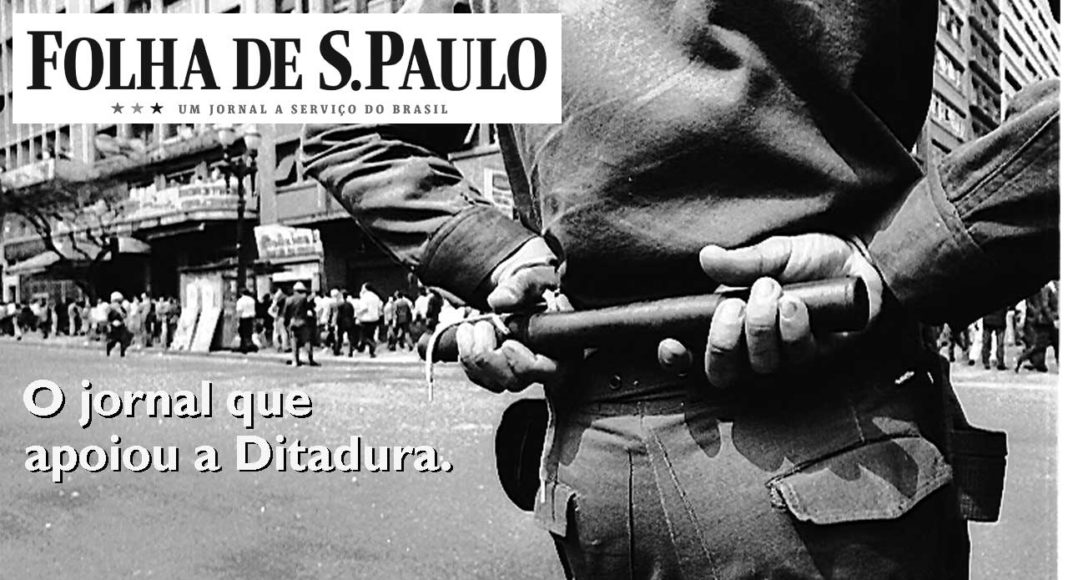

The title of this session is Media, Perception and the Consolidation of Brazilian Democracy. And it seems to me that some structural weaknesses in the Brazilian media are making it difficult to consolidate democracy. I’m not talking about individual journalists – some great professionals. What I’m talking about is the media industry itself. So I’m going to talk about the role the Brazilian press has played in current crisis. If I have time, I’ll also talk briefly about the role of the foreign press in the crisis, which I think has been unusual and interesting It is perhaps a bit of a truism to say that in Brazil the ‘grande imprensa’ – the mainstream press — is dominated by a few families, all of them of them highly conservative. Mino Carta, one of Brazil’s leading left-wing journalists and currently editor of Carta Capital, has described the Brazilian press as “reactionary and conservative”, and “attached by its umbilical cord to power and those holding power”.

- On the day before the impeachment was voted on, Globonews was reporting on the statements made for or against impeachment by deputies in the Chamber of Deputies. Globonews chose to leave the live transmission and to get a comment from one of its journalists or another commentator exactly when a pro-government (ie pro-Dilma) deputy was speaking. So it gave the impression – without actually saying it – that almost all the Chamber supported impeachment.

- Soon after Michel Temer came to office on 18 April, it was revealed that the main ministers in his new government were being investigated as part of the LavaJato (Car Wash) probe or were being cited in testimonies. This was clearly an important development – and widely reported by the foreign press. But it took the Folha de S. Paulo a fortnight to tell its readers about this development. And, according to Calle2, this only happened after it, Calle2, had contacted the Folha ombudsman. And even then, says Calle2, it wasn’t dealt with in a satisfactory way.

- When the Brazilian jurist Janaina Paschoal took part in a debate in the Senate on 28 April, she admitted that she had received 45,000 reais from the PSDB to draw up her parecer, her legal argument, which is the basis on which the demand for Dilma’s impeachment is being made. This is obviously an important piece of information because it suggests that the parecer may not be an impartial, legal document but something commissioned by the PSDB, which is the party which is pressing most strongly for the impeachment. But on the following day neither the Folha nor the Estadão newspapers had a report on this.