- In her second article on Ecuadorean environmental defenders, Linda Etchart highlights the voices of Indigenous activists who are campaigning for the removal of large-scale gold mining operations from a tributary of the Amazon in Ecuador and the battle with mining company TerraEarth.

- The first article of the series dealt with resistance to the expansion of Petroecuador’s oil fields in Dureno, half an hour to the east of Lago Agrio, in Sucumbíos, Ecuador, and events leading up to the assassination of Indigenous environment defender Eduardo Mendua.

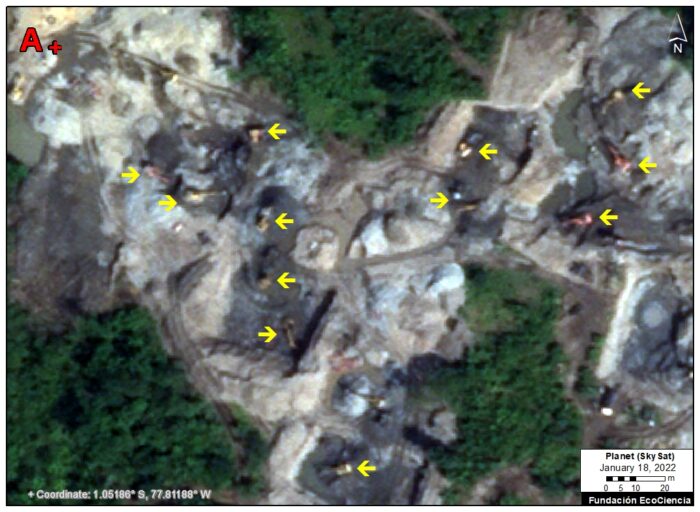

On 26 March 2023, environmental defenders on the Jatunyaku river, a tributary of the Amazon in Ecuador, in Yutzupino, called for help to protect the river from illegal gold mining. The Frente Nacional Anti-minero (National Anti-Mining Front) posted film footage on Facebook showing excavators operating on the banks of the river in defiance of a local court ruling – issued just two days earlier – which upheld a protection order based on the Rights of Nature.

Victory in the provincial court in Tena

The provincial court of Napo in Tena had ruled on 24 March in favour of a coalition of environmental groups, comprised of the federation of Indigenous organisations of Napo, decentralized autonomous parish governments (GADS), and social organizations.

In a communiqué on 26 March, one of the coalition’s Indigenous-led environmental groups, Napo Resiste, declared its support for the constitutional judge who determined that a protection order for the river issued by the government had not been honoured. The court ruled that the mining companies and the government had not carried out the restoration of the land that had been damaged by mining, as they were required to do by law. Napo Resiste blamed this failure on the Ministry of the Environment, the Ministry of Energy and Mines, and the Mining Regulation and Control Agency.

The following day, Napo Resiste posted on Instagram a film clip showing that ‘on 25 March, gold mining excavators were operating in Yaku Ñampi, only one day after the judge issued a protection order for failure to comply with the law.’

‘El pueblo se defiende. El Napo no se vende’

Napo Resiste has repeatedly denounced the contamination of the river by mercury and cynanide, and the destruction of flora and fauna caused by gold mining. They have demanded action from central government to include restoration of areas damaged by eight companies awarded concessions in the area, including by Chinese-financed company, TerraEarth, SA.

The film footage from 26 March showed gold miners ignoring signs indicating that the area was closed to mining. Two excavators, apparently belonging to TerraEarth, continued to operate while 100 protestors joined representatives of Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadoran Amazon (CONFENIAE), the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE), and the Federation of Indigenous Organizations of Napo (FOIN), in asking the miners to withdraw. The miners themselves merely laughed at the protestors in the absence of law enforcement.

This latest protest against gold mining in the Amazon is one of many popular mobilizations in mining areas in different parts of the country and all over the continent, where Indigenous and non-Indigenous environment defenders continue to contest their governments’ concessions to foreign mining companies, and to protest the failure of the authorities, including law enforcement, to prevent illegal activities that damage communities and the environment.

In the gold mining town of Zaruma, in El Oro province, illegal mining has created huge sink holes that have swallowed up entire buildings.

From the 1980s, there was an expansion of small-scale gold mining in Ecuador, which evolved into a goldrush in the early years of the twenty-first century, in the provinces of Sucumbíos, Orellana, and Napo, in the eastern Amazon region, and in the southern zone in the provinces of El Oro, Morona Santiago, and Zamora Chinchipe. In the gold mining town of Zaruma, in El Oro province, illegal mining has created huge sink holes that have swallowed up entire buildings.

Why the goldrush now?

During the global financial crisis of 2008, the price of gold rose and fell; in subsequent years, the price gradually climbed to reach over US$2,000 per ounce in 2023. Soaring demand has led to the proliferation of gold mines throughout Latin America, and the world over, to the benefit of goldmining companies, governments, as well as criminal cartels and networks. Equally it has had a devastating impact on the environment and on local and Indigenous communities who rely on the rivers for their survival.

In Ecuador, the twenty-first century fiebre de oro (gold fever) moved the extractive frontier eastwards into the Amazon basin under the administrations of Rafael Correa, Lenin Moreno, and Guillermo Lasso, despite the introduction of the Rights of Nature into the Constitution in 2008, the passing of mining laws in 2009 and 2013, and the Lasso government’s supposed commitment to halt gold mining on Indigenous land. This commitment was one element of a ten-point agreement with Indigenous groups in 2022. The 2009 mining act prohibits the use of mercury in gold processing: there is little evidence of this law being observed.

In the province of Napo, the Chinese company TerraEarth was granted gold mining concessions in 2010 covering 7,125 hectares. The company had a licence to prospect and mine gold in Vista Anzu and Regina in the Canton of Carlos Julio Arosemena Tola.

Different sources give conflicting evidence, but according to a 2018 government report, TerraEarth’s concessions relating to Confluencia, Talag, El Icho, and Anzu Norte, did not have environmental clearance, which meant that after 2017 the company was not able to operate the mines in Yutzupino, El Ceibo, Naranjalito, and Pioculin. In 2018, however, it was reported that 164 new mining concessions had been granted in the province.

Once in operation, the mines caused contamination of water sources and changes to water courses such as the Tuyano river, as well as deforestation and soil erosion. There was little evidence of the Ministry of the Environment putting in place measures of control, prevention, mitigation, or restoration, according to Fiodor Nicolay Mena Quintana, Presidente del Colegio de Ingenieros en Gestión Ambiental del Ecuador (CIGAE). In effect, local people and their environment had been abandoned by the government.

TerraEarth’s operations caused severe damage to the community of Nueva Esperanza and in El Progreso de Chumiyacu in 2019, it was reported. Trees were uprooted and destroyed, as well as crops of plantain and papaya. Yellow excavators were used to remove rocks and vegetation to a depth of 20 metres along the riverbanks. Pools 25 square metres or more in area were dug to separate sand from the gravel that contained the gold, with the industrial sluices (gravimetric concentrators known as zetas) consuming 800 gallons of water per minute. In the process of separating gold from the ore, aluminium, iron, magnesium, cadmium, chrome and nickel were released with the waste water, poisoning the land and the river.

Once the minerals had been extracted, TerraEarth was required by contract and law to restore the damaged areas so that they were no longer a risk to the environment or to human health, but in this case, this was not achieved, according to the Ecuadorian Ministry of the Environment. The earth was subsequently flattened out, but remains stony and contaminated, unusable for crops or livestock.

In December 2019, a group of Ecuadorian and Brazilian biologists published a study under the auspices of Ikiam University and the Universidad Católica de San Francisco, which showed that levels of cadmium, aluminium, iron, copper, zinc, nickel, and lead in the tributaries of the Napo River were 500 times higher than those permitted in Ecuador and north America, with levels around mines and landfills being 100 times those of other areas.

A subsequent study by Francisco Mestanza Ramón and colleagues conducted in 2021 found levels of mercury and cyanide 200-700 per cent above permitted levels in the tributaries of the Napo and other rivers where small-scale mining was taking place, with associated high incidence of cancer, indicating damage both to people and the environment.

Local communities mobilize

When in January 2020 TerraEarth announced that they were about to start prospecting and extraction in the parishes of Tena, Puerto Napo, Tálag, Pano, and in the canton of Carlos Julio Arosemena Tola, the Federation of Indigenous Organizations of Napo announced a meeting for 3 February to reject the project.

In October of the same year, TerraEarth once more ceased operations in Napo after 17 government inspections discovered contamination of the River Chumiyacu, as a result of the company’s diversion of river flow and failure to treat waste water. TerraEarth had failed to complete the required paperwork. On 26 October The Ministry of the Environment, Water and Ecological Transition (MAATE) issued a press release announcing the halting of TerraEarth’s operations in the area for failure to comply with environmental requirements by dumping toxic chemicals directly into the river.

Then in November of the same year, the community of El Progreso de Chumbiyacu, having previously agreed to loan out their property for mining, approached the Ombudsman, requesting an investigation into the company, and into the contractor, José Espinoza, in a bid to compel the company to restore the land. By this time, the communities of Nueva Esperanza and El Progreso de Chumbiyacu were drinking polluted river water, as they had no access to piped water.

A further scientific study published in February 2021 in the journal Water identified levels of pollution above the safety limit in water and sediment samples. The results showed unacceptable risks to the health of children and of adults from drinking the water or even from contact with the skin.

A litany of government failures

In a 400-page report on the case, the Ombudsman of Ecuador required demands for remediation and restoration be complied with, but the relevant government official reported that the Agency for Regulation and Control of Non-renewable Natural Resources had only one technician to cover the three provinces of Napo, Pichincha and Orellana; the Environment Ministry claimed to have only one technician to cover the two provinces of Napo and Orellana.

A group of local Indigenous Kichwa and non-Indigenous organisations — the Napo Defenders of the People, the Napo Indigenous People’s Federation, and the Napo branch of the Ecuadorian Peasants’ Defence Council Federation — took the case (for failure to restore the land) to the Provincial Court of Justice in Tena. Individual cases calling for remedial work were attached as an annex to the demand to the Court for protection of the Rights of Nature from gold mining.

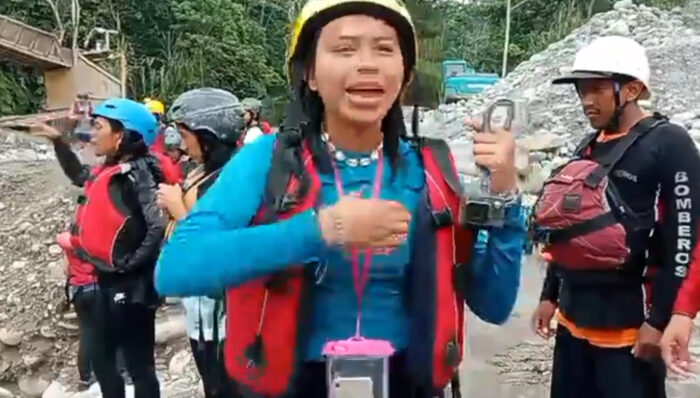

In spite of threats and intimidation by gold-mining interests, inaction — or complicity against them — on the part of local government, and a shortage of funds, environment defenders such as Majo Andrade Cerda persist in their campaigns to save their communities and the river, in taking cases to the local courts, in organising weekly demonstrations, in participating in global environmental governance at international environmental symposia around the world, and representing their nations at the UN headquarters in New York. In a few cases, Indigenous environment defenders have succeeded in their campaigns to protect their homelands from extractive interests, driving away companies who fear adverse publicity.

Indigenous environmental activists have been able to gain the attention of social media, of local and global press and television stations, and of those who hold political power, whom they have attempted to hold to account. In this task, (I)NGOs and non-Indigenous activist supporters have been essential allies in denouncing locations of illegal mining and the predations of private companies.

Yet Ecuadorian environmental activism is being conducted in an era when, as Majo Andrade Cerda points out, the Ecuadorian state is not functioning: ‘El estado es inoperante.’ While Indigenous voices have become louder, gaining prominence on the international stage, for the authorities, protecting the environment in Ecuador has taken a back seat in view of the country’s political and economic crisis.

Small country governments can only do so much, however. The global demand for commodities, legal and illegal, containerised transoceanic transport, and the absence of surveillance of huge container ports in Europe have made it almost impossible to prevent trafficking of illegal goods in recent years. These elements, combined with the ease with which cash is transferred in and out of large Western-owned banks and other shadow institutions with little oversight, mean that small countries with limited resources are now at the mercy of mafia bosses who are mostly beyond the reach of state judiciaries.

The next article in this series will chart what happens when large mining companies such as TerraEarth withdraw. Whether or not with their complicity, smaller, so-called ‘artisanal’ mining operations move into the space, spurring a mass influx – a goldrush – of opportunist individuals and groups. Small- and medium-scale miners are often financed by the cartels who provide mining equipment in the form of a loan: the gold production is in turn bought by illegally-operating middlemen linked to the cartels, creating a cycle of dependence.

It is the individuals at the very bottom of the chain, local people with few sources of income other than mining, who find themselves excluded, extorted or exploited by the gold mafias. Moreover, the local white-water kayaking business on the Jatunyacu river has been decimated: the goldmining has driven away many of the Ecuadorian and foreign kayakers, who provided welcome eco-tourism income. (Kayakers joining protests can be seen in the Instagram posts of Napo Resiste.).

The series will conclude by examining the ways in which Northern and Southern governments, banks, auditors and regulatory agencies, have until now failed to fulfil their promises to comply with laws and regulations, and to uphold and implement international standards, treaties and conventions in terms of business practices and the environment, creating the conditions in which criminality is enabled rather than controlled. It will also assess recent progress in the arrest, extradition and prosecution of key members of global criminal cartels that may be the first step in holding to account perpetrators of environmental crimes.

Linda Etchart is a lecturer in Human Geography at Kingston University. She is regular contributor to Latin America Bureau, and author of Global Governance of the Environment, the Rights of Nature and Indigenous Peoples: Extractive Industries in the Ecuadorian Amazon. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Main Image: Gold excavators on the Jatanyacu River, 11 February 2022. Mongabay. Image Iván Castaneira.

Sources and further reading:

Etchart, Linda (2022.1) “Financing for Development: Extra-Official Payments as Incentives for Development Projects.” Chapter 11, in Etchart, L. (2022) Global Governance of the Environment, Indigenous Peoples and the Rights of Nature: Extractive Industries in the Ecuadorian Amazon. London: Palgrave

Etchart, Linda (2022.2) “Indigenous Peoples and International Law in the Ecuadorian Amazon.” Laws 11, No. 4: 55.

Gabay, Aimée (2022) “Gold rush in Ecuador’s Amazon region threatens 1,500 communities.” Mongabay, 11 March 2022.

Gatehouse, Tom (2023) The Heart of Our Earth: Community resistance to mining in Latin America. Practical Action/Latin America Bureau.

Klein, David (2022) “Interpol: Illegal gold mining is devastating Latin America.” OCCRP. 6 May.

Mestanza Ramón, Carlos, Jefferson Cuenca-Cumbicus, Giovanni D’Orio, Jeniffer Flores-Toala, Susana Segovia-Cáceres, Amanda Bonilla-Bonilla, and Salvatore Straface (2022). “Gold Mining in the Amazon Region of Ecuador: History and a Review of Its Socio-Environmental Impacts.” Land 11: 221.

Organization of American States (OAS) (2021) Secretariat for Multidimensional Security. Department against Transnational Organized Crime. On the Trail of Illicit Gold Proceeds: Strengthening the Fight Against Illegal Mining Finance, Ecuador’s Case.

Organization of American States (OAS). Secretariat for Multidimensional Security. Department against Transnational Organized Crime. On the trail of illicit gold proceeds: strengthening the fight against illegal mining finances : Peru’s case.

Pelcastre, Julieta (2023) “OAS: Illegal Gold Trade from Ecuador to China on the Rise.”

Periodismo de Investigación (pi) (2022) “Minería ilegal en Napo: Se llevaron el oro mientras sembraban un cementerio: El río Yutzupino murió por causa de la minería ilegal y la tapiñada minería legal.” February 26.

Pieth, Mark (2023) “Delving into the shady world of gold laundering.” Corruptionwatch.