- In this article, the first of a series, Linda Etchart explains the complex background to the violent assassination in Ecuador of Indigenous environment defender Eduardo Mendua on 26 February 2023.

- Subsequent articles will ‘follow the money’, tracing how commodity profits move through international banking systems and global criminal networks, for which Ecuador has become an axis point.

- The series will show how the unrelenting demand for oil, gold, narcotics, timber and wild animals, has contributed to the elimination of the tropical forests of the Amazon and threatens the survival of the indigenous forest peoples.

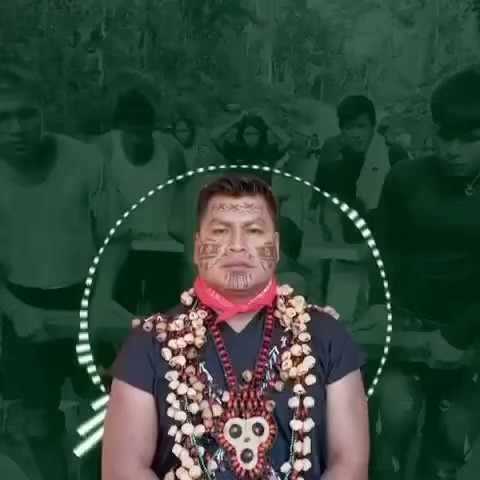

Indigenous environment defender Eduardo Mendua was assassinated at point blank range by two masked sicarios (gunmen) outside his home in Dureno on 26 February 2023, two days after he attended a meeting of CONAIE at which he publicly attributed to the government and Petroecuador responsibility for recent violence in the community of Dureno. He went on to appeal to the international community for support to defend Indigenous lands against further oil drilling, calling for the involvement of human rights organisations as witnesses.

Mendua’s murder demonstrates the tensions simmering beneath the surface among and between different sectors of the population in Ecuador, where inequalities have created competition for scarce resources, resulting in outbreaks of violence in both rural and urban areas. Levels of violence in the country have increased exponentially in the last 10 years, traceable to the pressures from outside forces and Ecuador´s strategic position in terms of the global demand for precious commodities.

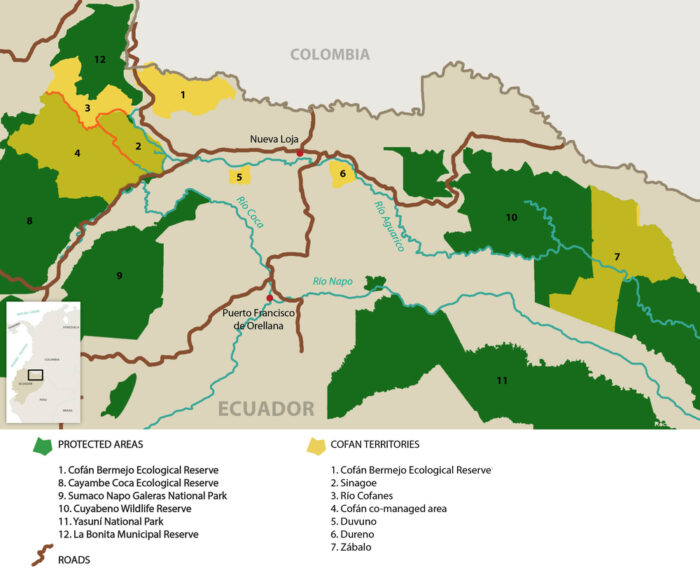

Eduardo Mendua was the Director of International Relations at the Confederation of the Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE), and a member of the resistance to the expansion of Petroecuador’s oil fields in his hometown of Dureno, half an hour to the east of Lago Agrio, in Sucumbíos, Ecuador.

The province of Sucumbíos was the site of Texaco’s 17 million gallon oil spill—the ‘Amazon Chernobyl’ of the 1970s and ’80s, that resulted in a multi-million dollar 20-year class-action suit against Chevron (see my three articles for LAB in 2018, updated in 2022 by Paul Paz y Miño).

A community divided

In the months leading up to Mendua´s assassination, a group of 130 Cofán environment defenders had been blocking Petroecuador’s plan to open 30 new oil wells in a concession overlapping Cofán territory, which covers 9,571 hectares of some of the only remaining forested part of the region.

The community of Dureno (Comunidad Autónoma Ancestral A’i Dureno) was divided over the proposed oil wells—one of the many intra-communal conflicts provoked by the activities of extractive industries in the continent. Oil and mineral extraction provides jobs to small communities whose access to resources has been eroded by clearing of forest and contamination of rivers: extractive activities cause hardship, thereby creating vulnerability to offers of financial assistance. This phenomenon has been described by the legal anthropologist Lindsay Ofrias, as the ‘incentive to contaminate’.

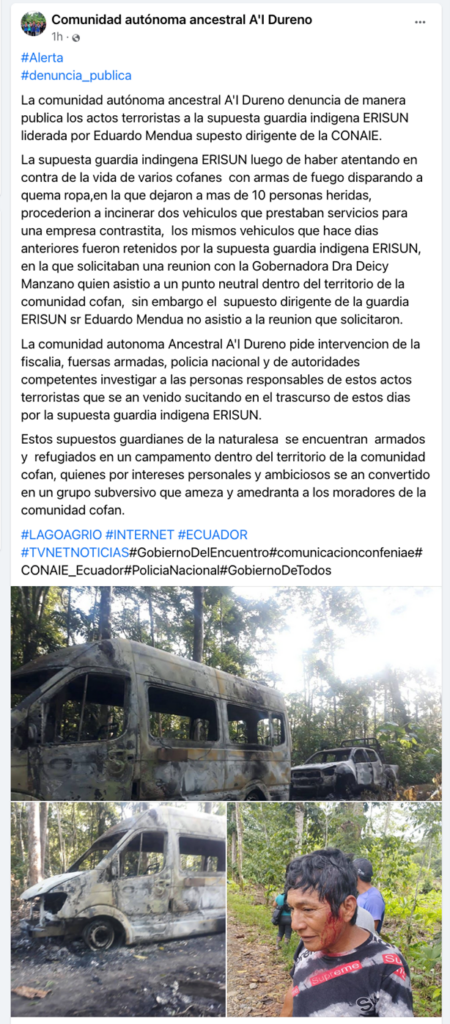

A key moment in the dispute took place on 12 January 2023, when a group of Cofán anti-oil protestors, of which Eduardo Mendua was one, prevented the entry into the proposed oil drilling area of a team of Cofán workers who were there to survey the site for possible archaeological significance.

A confrontation took place among the pro- and anti-oil sides. Four police and a large group of Cofán supporters accompanied the pro-oil contingent to assure their safety. There were gunshots: 16 Cofán people suffered injuries, 10 on the pro-oil side and 6 on the anti-oil side. The police fired tear gas to disperse the anti-oil protestors. Reportedly, one of the police was shot as well, but his bulletproof vest prevented him from being hurt.

Luckily no one was killed, but it is possible that the incident may have had a bearing on Mendua’s assassination the following month. The confrontation was recorded and shared on social media: members of the pro-oil element posted a denunciation of Mendua and his group on 14 January after Mendua’s allies burned and destroyed two vehicles they had confiscated from the pro-oil group, which had used them to try to get to the drilling site at an earlier date.

The evolution of the conflict

According to CONAIE, the conflict had arisen because the president of the Dureno Cofán community, Silverio Criollo, had signed an agreement with Petroecuador five years ago, allegedly for US$5 million, giving permission for the company to build a road and drill for oil on communal Cofán territory in return for payments being given to each member of the community and some goods for the community.

Mendua opposed the agreement on the grounds of failure to consult with all of the members involved, as required by the Free, Prior and Informed consent (FPIC) clause of the Ecuadorian Constitution that pertains to Indigenous nations within Ecuador. Serious confrontations broke out when Petroecuador began operating in June 2022, and the project was halted.

On 12 January 2023, Mendua denounced the agreement. In a tweet on 27 February 2023, after his assassination, CONAIE relayed Mendua´s January message in which he also said that the government of Guillermo Lasso was stirring up violent conflict among the A’i Cofán people. A friend and colleague of Mendua, Edwin Hérnandez, commented in addition that the Cofán leadership under Silverio Criollo had been imposing fines on those who opposed the oil agreement, creating further discord.

The government and Petroecuador had apparently been willing to negotiate, but time was running out, as Petroecuador had threatened to take action by mid-March 2023 if the case had not been resolved by then, on the grounds that payments had already been distributed among the population.

Permanent mobilisation

Delegates at the CONAIE meeting had agreed to hold a ‘permanent mobilisation’ and to radicalise the struggle in Indigenous territories as a response to the government´s failure to fulfil the promises made by President Lasso in June 2022, following the indigenous protests and the general strike against the government that year. On that occasion, the indigenous movement led by Leonidas Iza called off the general strike on the condition that the agreed 10-point plan would be implemented within six months.

The death of Mendua led to widespread denunciations of the government and of Petroecuador by environmental movements and opposition parties. The government itself announced that four houses had been searched by the police, resulting in the impounding of four guns, eight rounds of ammunition, five mobile phones, a canoe and an outboard motor. One person was being held in custody. Suspects in Ecuador are not named, so he was described as ‘David Q’. There was said to be circumstantial evidence implicating this person, who was not thought to be a contract killer himself, but was in the area at the time.

Both the Ecuadorian government and indigenous organisations including CONAIE and CONFENIAE condemned the assassination of Mendua. Ecuadorian president Guillermo Lasso tweeted: ‘The government of Ecuador declares its solidarity with the family of Eduardo Mendua and with CONAIE. This crime will be punished. We have ordered an investigation to find those responsible and prosecute them.’

Despite Lasso’s offer, CONAIE president Leonidas Iza declared that he was holding the government and the oil companies responsible for the murder. Calling for unity of the indigenous movement, Iza described Mendua as one of the most prominent defenders of Cofán territory, engaged in a struggle to end exploitation and oil contamination of the Amazon.

On 28 February, CONAIE demanded that Silverio Criollo’s presidency of the Cofán be revoked, and that his agreement with Petroecuador be annulled. They announced that they would take the case to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.

The murder was also condemned by Professor Alberto Acosta, buen vivir scholar, former Minister of Mines and Energy, and architect of Ecuador’s 2008 Constitution which incorporates the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the Rights of Nature. In a tribute to Mendua, Acosta quoted Mendua´s last Facebook post:

‘We are determined and strong as ever, we will not concede a centimetre of our territory for foreign petroleum companies to destroy the spirits and invisible people of our forest, rivers, lakes, sacred places, ravines, medicinal herbs, our ceibo trees.’

‘…nos mantendremos más firmes y fuertes que nunca, no estamos para ceder ni un centímetro de nuestro territorio para que los forasteros petroleros destruyan a los seres espirituales y personas invisibles de nuestra selva, ríos, lagunas, lugares sagrados, quebradas, medicina, nuestros ceibos.’

A lost battle

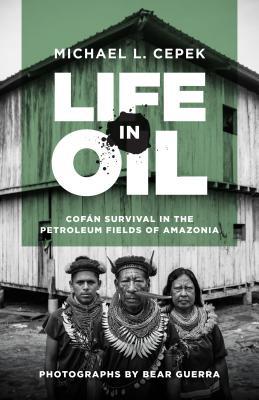

Of all the indigenous communities affected by the transnational petroleum industry in the American continent over the last century, Dureno is probably one of those that has suffered the most, from the 1960s to the present. The province of Sucumbíos has been the site of multiple oil spills. This has meant that the inhabitants of affected communities have been consuming oil-contaminated food and water, and breathing oil-contaminated air for 50 years, resulting in high rates of cancer. Their experience has been carefully documented by Professor Michael Cepek, author of Life in Oil: Cofán survival in the petroleum fields of Amazonia (2018).

In 1987, the Cofán began a protest against Texaco´s oil drilling around Dureno, succeeding in halting their operations. The following year, with the help of the environmental NGO Acción Ecológica, they took over and forced the closure of Dureno 1, the only active well operating inside the boundaries of the Cofán community. Texaco withdrew in 1992 and were succeeded by Petroecuador. This was a major victory, promising to keep oil drilling out of the area. It did not last. In 2013 a Chinese oil company BGP began seismic testing on behalf of Petroecuador.

By this time, however, there was a disillusionment among the Cofán who saw non-indigenous communities of environmental activists obtaining greater benefits than themselves. The Cofán felt that they had paid the price of being designated by others as ‘noble savages’, an objectification aimed at preserving them as the Other, as museum pieces, preventing them from running their own lives in the way they wanted.

Cepek’s immersive research for Life in Oil reveals that by 2012 many Cofán knew that they could no longer resist the oil companies and the government, that their communities would never be the same, that in some ways the damage was irreparable. In these circumstances, many of them made the decision to cut their losses and to accept the compensation and reparation that was on offer.

Following the (unsuccessful, to date, but still ongoing) class action lawsuit again Texaco-Chevron, and the victory of the Sarayaku Kichwa people against the Ecuadorian government at the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in 2012, the government of President Correa then found itself obliged to follow the law and comply with environmental and human rights treaties.

Hence when it came to plans to open up the Sucumbíos oil fields once again, Petroecuador embarked upon a different tack which involved paying compensation and securing the agreement of indigenous people who inhabited areas rich in oil. It also did a far better job than Texaco in complying with environmental regulations.

So when the Chinese oil company BGP (part of the Chinese National Petroleum Corporation) arrived in Dureno in 2013, and set off underground explosive charges in the search for oil deposits, a sum of US$1,000 was paid to each member of the community, and an outboard motor valued at around $2,000 was given to each family. Housing and medical care were provided, as well as university scholarships. A similar agreement was made the same year with Petroamazonas to reopen the Dureno 1 well that the Cofán had closed, as well as to expand another well which would infringe community boundaries.

Under the Correa administration, once the oilfields were established, the wastewater was collected and stored – in contrast to Texaco´s numerous oil-extraction facilities, where wastewater was left to seep into underground water sources and streams.

Why did the Dureno Cofán sign up to oil drilling?

The contamination of water sources from Texaco´s operations was so extensive that it was impossible to remedy. The Cofán were suffering from high levels of cancer and required support. Their previous way of life was becoming more and more difficult to maintain, or regain. Game was no longer abundant: hunting parties came home empty handed, so they had to find other sources of food. They increasingly needed cash income to buy fuel oil, clothes, refrigerators, and other items that the forest could not provide.

They received payments for ecosystem services under Ecuador’s SocioBosque programme, connected to the UN Redd+ initiative to protect the world’s last remaining old growth forests. During the Correa administration, they received US$54,000 per year as payments under the scheme. Some also received payments of $35,000 per year for allowing a company to dredge rocks from a river to build roads.

Mendua himself played a key role in a new programme set up by the Correa administration to build a ‘millennium community’ in Dureno where each family was allocated a house worth US$45,000, equipped with water and sewage systems. The community was provided with schools, internet access and satellite television. Cepek quotes a figure of US$10 million dollars’ worth of benefits over three years. Even then, and although a US non-profit provided the community with water tanks, people continued to suffer the effects of the air pollution produced by the flaring of oil wells, which also contaminates the rain and poisons the main sources of drinking water for the population.

Mendua´s projects were successful, possibly causing resentment among some of his contemporaries. He was an ally of Correa, who himself became a divisive figure among some indigenous communities who continued to resist the expansion of the extractive industries in their territories. Mendua was convinced that the new agreements with BGP and Petroamazonas would be beneficial to the population and result in oil drilling that would be less damaging to the environment through strict adherence to regulations and new technology. His plan was to use oil proceeds to build high-class tourism for when the oil ran dry.

But even by 2013, divisions were emerging within the community, with a report of violence erupting at a community meeting between those in favour of oil drilling and those against. Younger people tended to support oil drilling; many older people resisted it.

There were convincing arguments for signing up with oil company: that the drilling would go ahead anyway from outside Cofán territory, with contamination continuing unabated; that the oil-derived income would mean less need to hunt for game, thereby protecting biodiversity; that young people would stay rather than move away, and the culture would be preserved.

Mendua´s bitter choice?

Why did Mendua’s position appear to change from one of advocating for Dureno´s majority, who did not want oil, but had lost the will to resist it, to mobilising against it?

An interview with Eduardo Mendua from June 2022 – at the height of the uprising of both indigenous and non-indigenous protestors against the government of Guillermo Lasso – throws light on his political philosophy.

It has to be viewed in the context of Mendua´s alliance with Rafael Correa, whose first action when taking over the presidency in 2007 was to change the Constitution in favour of indigenous peoples and protection of the environment; and Mendua’s close relationship with Leonidas Iza, leader of CONAIE and of the 2022 uprising.

Correa´s administration (2007-2017) found itself engaged in a balancing act in attempting to defend the rights of all sectors of the population, particularly the poor and the marginalised, through providing health, education, employment and infrastructure, while at the same time protecting the environment. The government had to find a way to service the country’s debts: one of the few ways of doing so was to sell the country’s natural resources, such as oil and minerals, in return for loans.

In the interview shown on YouTube above, Mendua explains why the insurrection took place in terms of opposition to the rise in the price of gasoline, using the moment to present his vision for the plurinational Ecuador of the future. He argues that Ecuador has an abundance of natural resources, including oil and minerals, bananas, cocoa, tuna and shrimp, sufficient to ensure that the whole population could enjoy a good standard of living. ‘We can produce all we need’, he says. He denounces the country’s urban elites for enriching themselves at the expense of the rural poor, the marginalised, and the homeless.

While endorsing the plurinationalist state, Mendua laments white and mestizo racism against the country´s indigenous peoples who are now taking the lead to create a more egalitarian country where everyone could share in the country´s wealth: ‘We want to change the system for 18 million Ecuadorians, to transform the Ecuadorian state.’ He argues that the lack of social justice had brought the disadvantaged sectors of the population in rural and outlying urban areas to support indigenous leaders in their resistance to neoliberalism.

Mendua accuses the government of Guillermo Lasso of persecuting indigenous leaders and attempting to kill Leonidas Iza, instead of addressing the violence overwhelming the country caused by narcotics traffickers. He says: ‘We can’t go on living like this: the violence has got very bad.’

Mendua’s aspiration for indigenous peoples in Ecuador was for titles to their ancestral territories, self-determination, that is, the rights which they had been denied by the colonisers and later also by the mestizo population. In the interview, Mendua describes the working conditions of indigenous peoples as being similar to those of undocumented workers, having temporary contracts, little access to health care and no pensions. In his analysis of the Ecuadorian economy, Mendua points out that the billions of dollars received for the country´s mineral wealth could be used to subsidise petrol prices, which were unsustainable for the poorest sectors of the population.

His line of argument is consistent with that of the ten demands made by CONAIE to the Lasso administration, to which the government ultimately conceded on 30 June 2022:

CONAIE´s demands

- Reduction and freezing of the prices of fuel: diesel at $1.50 and extra and eco gasoline at $2.10. Abolish Decrees 1158, 1183, 1054, and focus instead on the sectors that need more subsidies: agricultural work, farming, transportation and fishing.

- Economic relief for more than four million families with a moratorium of no less than one year, renegotiation of private debts with a reduction of interest rates, and the suspension of seizure of assets due to non-payment of those debts.

- Fair prices on everyday food products and no royalty payments for farmers.

- Policies and public investment to prevent or avoid job insecurity and the demanding of payment of debts to the IESS.

- Moratorium on the expansion of the mining and oil industries, comprehensive audits and reparations for the sociological and environmental impacts of these industries, and the repeal of Decrees 95 and 151 on mining.

- Respect for the twenty-one collective rights provided for in Article 57 of the Constitution: bilingual intercultural education, indigenous justice, prior consultation, and organization and self-determination of indigenous communities.

- Stopping the privatization of public companies.

- Policies to control prices and speculative pricing on basic necessities.

- An urgent budget in the face of shortages in hospitals due to a lack of medical personnel and staff. Guaranteed youth access to higher education and the improvement of infrastructure in primary schools, secondary schools, and universities.

- Security, protection, and generation of effective public policies to curb crime in the country.

It is in the light of a class-based analysis that Mendua’s position can be understood. His inconsistencies reflect those of CONAIE in their demands of the government, that is, a halt to oil drilling in indigenous territories and a reduction in the price of gasoline, which appear contradictory, but which demonstrate the reality of a country generating enormous wealth for the elites at the cost of the health and wellbeing of indigenous, rural and marginalised peoples. The escalating levels of violence in Ecuador’s coastal cities are another aspect of the consequences of poverty and alienation in countries that have abundant resources from which the majority of the population do not benefit, labelled by Alberto Acosta as la maldición de la abundancia, the resource curse, a theme which will be expanded upon in the next article of this series.

Further reading

Acosta, Alberto (2023) “Quién mató a Eduardo Mendua? Más allá de quien disparó el arma asesina.” Amazonia latitude, 7 March 2023. https://www.amazonialatitude.com/2023/03/07/quien-mato-a-eduardo-mendua/

Becker, Marc (2014) “Resource Extraction and Yasuní National Park: Ecuador’s Bitter Choice.” Analysis 10. January/February. http://solidarity-us.org/files/ ATC%20168–Becker.pdf.

Cepek, Michael (2018) Life in Oil: Cofán Survival in the Petroleum Fields of Amazonia. Austin: University of Texas Press

Etchart, Linda (2018) “Chevron, Ecuador and the Extractor’s Curse.” Parts 1–3. London: Latin America Bureau, Available online: https://lab.org.uk/chevron-ecuador-and-the-extractors-curse-1/ (accessed on 18 August 2020).

Etchart, Linda (2022) Global Governance of the Environment, Indigenous Peoples and the Rights of Nature: Extractive Industries in the Ecuadorian Amazon. London: Palgrave

Ofrias, Lindsay (2017) “Invisible harms, invisible profits: A theory of the incentive to contaminate.” Culture, Theory and Critique 58: 435–56

Gatehouse, Tom (2023) The Heart of Our Earth: Community resistance to mining in Latin America. Practical Action/Latin America Bureau.