I chose to abstain from attending COP28 in Dubai, which closed on 13 December, partly due to the disillusionment I experienced at the last COP in Egypt in 2022. I had witnessed repeated forms of climate denialism – promises made without the capacity to deliver, band-aid solutions, and techno-salvationist fantasies that cannot countenance the possibility that white supremacist institutions and the various forms of imperialism are both unsustainable and in a state of terminal decline.

The summit failed to consider the ways of those who live and coexist with nature, and have been doing so before the dawn of ‘civilization’, despite the historic and ongoing depredations of settler colonialism and necrocapitalism.

This has led me to feel that such conferences are merely performative, a smokescreen to conceal the actual state of things on our planet. Instead of listening to such performances, I decided that this year, I’d spend my time in the Amazon rainforest, returning only now, early in the new year.

Since Covid-19 erupted into our lives, I have spent much of my time as a documentary filmmaker in Brazil, Peru, Colombia, and Ecuador. As such, I’ve been forced to grapple with unsettling questions about our future. This has led me to recognize a stark truth: Indigenous peoples cannot bear the sole responsibility for saving our planet.

In recent years, discussions centered around Indigenous perspectives on the environment have gained momentum, illuminating native peoples’ distinctive approach to land conservation. As we contemplate the challenges faced by Indigenous communities – especially within the context of ongoing environmental crises – it is imperative to view the collective wisdom contained within their diverse cultures as a valuable tool for imagining democratic and ecologically-informed solutions for a just future for humans and all living organisms.

Contrary to common misconceptions, the Indigenous peoples of the Americas do not see themselves as ‘saviours’ of the environment. Instead, their message is clear – without collective efforts and collaborative alliances, humanity will certainly fail to address the environmental challenges we face as a species.

While many Indigenous communities are in the vanguard of various environmental movements, it’s critical to acknowledge the social wisdom informing their repeated calls for unity and solidarity across lines of national, ethnic, cultural, linguistic, and human identity. Who is willing to join forces with these peoples to think, feel, and imagine our way toward something better?

Memory and knowledge

One significant aspect of Indigenous thinking highlights the importance of memory and ancestral knowledge. ‘The future is ancestral. It is everything that has already existed. It’s not something that is simply out there some place. It is what is right here,’ says Indigenous leader, philosopher, writer, and new member of the Academia Brasileira de Letras (Brazilian Academy of Letters), Ailton Krenak.

Indigenous communities emphasize the need to preserve and embody their cultural traditions. These are by no means static: they constantly evolve in response to the pressures of history and lived experience. For the Indigenous peoples, the future is deeply rooted in the past. This worldview creates unique, complex, and highly imaginative temporal landscapes that unsettle linear notions of progress.

Reflecting on the outcomes of COP28, my mind went back to a pivotal panel discussion hosted during COP26, deftly moderated by The New York Times columnist, Thomas Friedman. This exclusive assembly – which included Dr. Akinwumi Adesina, President of the African Development Bank, Julia Gillard, former Australian Prime Minister and Chair of the Wellcome Trust, and Mari Elka Pangestu, the World Bank’s Managing Director of Development Policy and Partnerships – centred its deliberations on envisioning, planning, and executing strategies that infuse equity and resilience into the infrastructure of tomorrow.

As I reflected upon the panel discussion, I could not help but wonder: what tangible changes have occurred since then?

Dr. Adesina’s words continue to echo within me: ‘Losses for Africa are immense. We lose US$7 to 15 billion a year right now because of climate change. If that doesn’t change in terms of creating adaptation, that’s going to grow to roughly US$50 billion by 2040.’ Turning to the vital need for investment in infrastructure, he added: ‘The reason we [humans] walk is because we’ve got column vertebrae that allow us to do that. That’s what infrastructure is. If you have good infrastructure, your economy works. If you have better infrastructure that’s green, it’s much better. We need to invest a lot more in infrastructure.’

After the panel I asked Thomas Friedeman directly whether he recognized the environment’s crucial role in the world’s infrastructure. He replied that he did. In the limited time available, I pressed further: ‘Do you consider the Amazon to be infrastructure?’ He responded, ‘I’ll have to think about it.’

To me, that panel discussion revealed a fundamental question: why don’t we consider the environment itself as part of our infrastructure? Indigenous voices question the prevailing paradigm that views natural resources merely as commodities to exploit. This perspective challenges us to rethink the very foundations of our societal structures and advocate for the protection of natural infrastructure.

While documentary films and academic discussions can play a crucial role in raising awareness about climate change, the real challenge lies in implementing tangible solutions. Indigenous thinking provides an alternative framework for environmental protection that helps us to see beyond the limited purview of capitalism. It asks us to recognize the interconnectedness of all living beings and embrace a collective responsibility to safeguard our planet.

In our pursuit of solutions, we must acknowledge that Indigenous communities cannot bear this responsibility alone. Their call for collective action and mutual understanding is an invitation to forge alliances and work towards a future shared in common. Let’s move beyond the rhetoric of environmentalism and actively engage with the knowledge-systems that have sustained diverse ecosystems for millennia.

In my recent visit to Ecuador, I was able to better understand three notable cosmologies rooted in the country’s diverse Indigenous philosophies: Sumak Kawsay, Kawsak Sacha, and Tarimiat Pujustin, all of which humbly strive to illuminate complex, dynamic relations of interdependency between humanity and nature (often tragically obscured by Western science, as well as the forms of cultural anthropocentrism that shape its pretentions of objectivity).

- Sumak Kawsay, popularly translated as ‘Good Living’, emerges from the Andes, proclaiming a life in balance and harmony between people and nature.

- In the vast Amazon rainforest, Kawsak Sacha, or ‘Living Jungle’, celebrates the spiritual connection between nature, humans, and the cosmos.

- Lastly, from the Shuar world, Tarimiat Pujustin, reflects a good life in their own territory and the care of nature, suggesting an intimate glimpse into Indigenous relations with the land and the more-than-human world.

These concepts converge in a call to recognize the interdependence of all forms of life and to adopt a collective approach to safeguarding our planet.

As we grapple with complex environmental issues, integrating Indigenous perspectives into mainstream discourse is not only a step towards justice, but a practical path forward. It’s time to move beyond mere acknowledgment and actively involve Indigenous communities in shaping environmental policy and strategy. By doing so, we can collectively strive for a future where environmental protection is not a choice, but a shared responsibility borne by all.

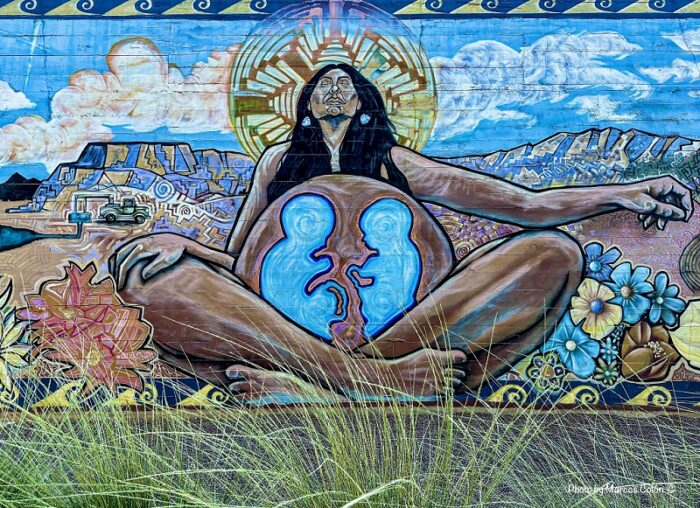

Main image: photomontage by Marcos Colón

Dr. Marcos Colón is an Assistant Professor in the International Affairs Program at Florida State University. He is the director, writer and producer of Beyond Fordlândia: An Environmental Account of Henry Ford’s Adventure in the Amazon (2018) and Stepping Softly on the Earth (2022). His forthcoming book, The Amazon in Times of War, is set to be released in the summer of 2024.