FAO officials are making optimistic predictions about eliminating hunger over the next few years but this ignores climate change, which will present a big risk for the continent.

“We could be the last Latin American and Caribbean generation living together with hunger.”

The assertion, made by Raúl Benítez, a regional officer for the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), shows one side of the coin: only 4.6 percent of the region’s population is undernourished, according to the latest figures.

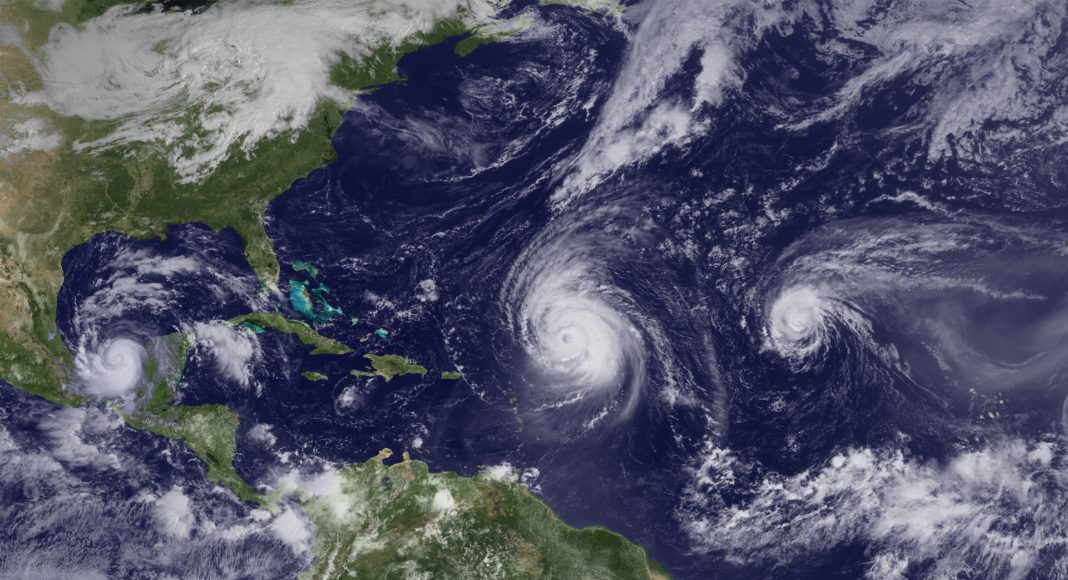

By 2030, however, most of the countries in the region will face a serious risk situation due to climate change.

With almost 600 million inhabitants, Latin America and the Caribbean has a third of the world’s fresh water and more than a quarter of its medium to high potential farmland, points out a book published this year by the Inter-American Development Bank in partnership with Global Harvest Initiative, a private-sector think-tank.

It is the largest net food-exporting region, while it uses just a fraction of its agricultural potential for both consuming and exporting.

But almost a quarter of the region’s rural people still live on less than two dollars a day, and the region is prone to disasters (earthquakes, hurricanes, floods and droughts), some of them exacerbated by climate change.

Global warming poses serious challenges to the international community’s goal of eradicating poverty and hunger. Changes in rainfall patterns, soils and temperatures are already stressing agricultural systems.

Currently, more than 800 million people worldwide are at risk of hunger. Through its devastating impact on crops and livelihoods, climate change is predicted to increase that number by as much as 20 percent by 2050, according to arecent United Nations report.

Changes in temperature and rainfall patterns could lead to food price rises of between three percent and 84 percent by 2050, thereby feeding a vicious cycle of poverty and inequality.

Oxfam reports that in the more extreme scenarios, heat and water stress could reduce crop yields by 25 percent between 2030 and 2049.

Climate change is likely to impact mostly small and family farmers, who produce more than half the food in the region and have inadequate resources with which to deal with unpredictable weather.

Despite this looming threat, strategies for sustainability are far from clear. Regional drivers of growth are export-oriented commodities, and while some sectors have advanced in added value, technology and innovation, natural resources exploitation is still the key of the whole regional boom.

A traffic jam in Jaciara, Brazil, caused by repairs to the BR-364, geared to improving the export infrastructure for commodities. Credit: Mario Osava/IPS

By 2011, raw materials and commodities accounted for 60 percent of regional exports, compared to 40 percent in 2000. At the same time, this growth of commodities exports led to a replacement of domestic manufactures by imported goods, affecting manufacturing industries in the region.

In rural areas, conflicting models of small farming and extensive monocultures based on genetically modified seeds compete for the land in a David versus Goliath fight.

In Paraguay, the fourth largest exporter of soybeans in the world, 1.6 percent of owners hold 80 percent of the agricultural land. In Guatemala, eight percent of producers own 82 percent of farmlands, while 80 percent of productive land in Colombia is in the hands of 14 percent of landowners, according to Oxfam.

Agriculture and related deforestation are major sources of greenhouse gasses (GHG) in Latin America, though other sources are growing rapidly. Brazil, for example, is joining the club of big polluters, with the burning of fossil fuels accounting for the majority of its GHG emissions in the last five years.

As the extractive industries grow, they demand more highways, railroads and ports, putting pressure on governments to avoid the so-called logistics blackout.

Energy demand is increasing too, not only from industries, but also from millions of people lifted out of poverty, and thus with larger consumption needs. The region’s energy demand for the period 2010-2017 increases at an annual rate of five percent.

The region is poised to cross a new fossil fuel frontier, when Argentina, Brazil and Mexico overcome their own political, financial and technical challenges to exploit substantial reserves of unconventional hydrocarbons, like the Argentinian Vaca Muerta geological formation or the pre-salt layer located in the Brazilian continental shelf.

It is difficult to argue that a region so rich in natural resources has no right to thrive on the demand and supply of commodities, particularly when the resulting fiscal revenues have allowed impoverished countries like Bolivia to drastically reduce extreme poverty numbers (from 38 percent in 2005 to 20 percent in 2013).

However, experts warn this path is unsustainable and climate change impacts, felt across the region, can undermine any social gain.

In Guatemala, the worst drought in 40 years is putting 1.2 million people at risk of suffering hunger in the next months. Those who suffer the worst impacts of unsustainable development models will ironically be those who contribute the least to global warming.

A recent U.N. document summarising actions for the follow-up to the programme of action adopted at the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) found that only about a “third of the world’s population could be considered as having consumption profiles that contribute to emissions.”

Fewer than one billion of them have a significant impact, while “a smaller minority is responsible for an overwhelming share of the damage,” the report added.

Still, it will be the poorest people who will bear the brunt, and Latin America, dubbed ‘the next global breadbasket’, is in desperate need of strong local and global action towards the goal of achieving sustainable development in the next decade.

Edited by Kanya D’Almeida