‘Without seeing a teacher in person, children aren’t receiving a sufficient education,’ a concerned mother of two based in central Mexico told me, late last year. ‘The level of education children are getting is just not the same.’

Her view was representative of many, as thousands of Mexican parents battled with work in unstable jobs, while avoiding COVID-19 and educating their children from home.

Since then, classroom doors have reopened, albeit much later than in other Latin American countries. Needless to say, the pandemic has had an irreversible impact on education across Mexico. But can hundreds of lost school days be recovered for the children in greatest need?

The true cost of home learning

As in many countries across the world, learning moved online in Mexico as the pandemic struck. Teachers and students worked in virtual classrooms, while parents effectively became professors overnight.

According to Juan Martín Pérez García, coordinator of Weaving Childhood Networks in Latin America and the Caribbean (Tejiendo Redes Infancia en América Latina y el Caribe), an initiative that seeks to defend and promote the rights of children and adolescents in the region, school closures affected around 30 million young people.

Organizations like Tejiendo Redes and UNICEF Mexico tried to help with the nation’s hasty adjustment to home learning, in an effort to safeguard child rights.

UNICEF, for example, provided parents with top tips where the government fell short. They advised adults to take care of the emotional health of their sons and daughters, establish a set routine for the day, manage time well, and check their children had study supplies. The organization also reminded parents that they were not expected to be fully-qualified teachers.

But many felt the need to take on that responsibility, balancing work and, in some cases, efforts to avoid poverty, with fraught attempts to become their child’s own personal teacher overnight.

‘Parents have lots of work to do when it comes to education: they don’t just have to go out to work, but by night they become their child’s teacher,’ a mother of two under-10s from the state of Puebla told me late last year. For her, it became a case of splitting her life in three: work, supporting her children with their online classes and teaching them herself to fill in the gaps.

She told me that being a mother of two had meant double the stress, for herself, her husband, and the children themselves. ‘I can’t imagine the situation for those that have more children,’ she said.

She added that some children did not have the technical resources (i.e. a reliable Wi-Fi connection) to keep up with online learning.

Schools too had to adapt to a new way of doing things. A kindergarten teacher and mother of one based in the city of Tehuacan, Puebla state, talked about the difficulties private schools like her own had experienced with online learning via videocalls. She mentioned that classes were easily interrupted and that some parents did not understand instructions they were given.

She added that, on the other hand, some public schools did not even try to introduce home learning via online classes. They simply sent children home with ‘learning guides.’

Juan Martín Pérez García added that Mexico’s public education system had not invested in learning technology (i.e. tablets for students), instead relying on television programmes to launch distance learning. A resulting lack of direct interaction with teachers meant that children were cut off from their educational communities, causing what he called a ‘learning crisis’.

Meanwhile, teachers faced their own share of challenges beyond the logistical difficulties of online learning. Some were not paid.

While teachers in Mexico’s public school system receive their pay packets directly from the government, those in the private sector rely on payments made by parents whose children are enrolled in their respective institutions.

The kindergarten teacher revealed how some parents in the preschool she works at refused to pay, stating that their child’s learning was suffering and that they were paying for a service that had little benefit. ‘It affected me a lot on an economic level,’ she said, adding ‘[my job] is the main source of income for my small family.’

Back to school

Full home-schooling came to an end 17 long months after schools first closed their doors in Mexico.

In August of this year, during the pandemic’s third wave, over 25 million students returned to pre-, primary and secondary school, once they were given the green light by the government of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

While AMLO welcomed the new academic year of in-person teaching in one of his morning press conferences, parents had mixed feelings. Some were relieved to see their children get back to class, with others reluctant, citing a lack of anti-covid measures in place.

The responses of different states were also mixed. Baja California Sur and Sinaloa put off the return due to hurricane Nora, while Michoacán felt it wasn’t the right moment. Meanwhile, Jalisco’s governor emphasized parents who felt uncomfortable could keep their children learning online. 1.5 million students were expected to go back to primary school in that state alone.

But simply reopening school doors may not be enough to resolve the challenges bequeathed by coronavirus.

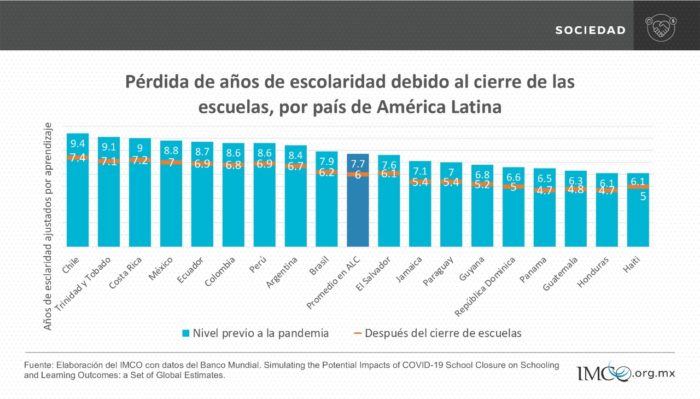

In June, the Mexican Institute for Competitiveness (Instituto Mexicano para la Competitividad – IMCO), an NGO that has studied inclusivity in society and corruption, estimated that around 10 million children may now have fallen two years behind in their studies due to classroom closures during the pandemic. This may have a disastrous impact for future employment prospects.

The findings of a recent report published by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) indicated Mexico may suffer these consequences to a greater degree than its regional counterparts.

It underlined that while pre-, primary and secondary schools were mostly closed for between 55 to 92 days in OECD member states, in Mexico this figure amounted to 210 school days.

Worryingly, it added that Mexico has the highest ‘out-of-school rate.’ More than 25 percent of young people that should be in upper secondary school are not enrolled. Over five million students did not enrol themselves for the 2020-2021 academic year, citing covid-related reasons and money difficulties.

School dropout is a long-term problem in Mexico that appears to have worsened considerably during the pandemic. It comes with a string of consequences.

When a child or teenager is out of school, he or she also becomes much more vulnerable to criminal groups seeking to recruit new members. Juan Martín Pérez García revealed that, in some cases, criminals have provided services where the State has not, which has allowed them to strengthen social support.

Many children also lost their social networks – teachers, extended family members and neighbours – during lockdown, Pérez García added. This led to a dramatic rise in domestic violence and sexual abuse against children and teenagers with no escape.

A New Chapter?

It is too early to say whether the pandemic will permanently change education as Mexico knows it today. It is too soon to know how efforts to recapture a lost generation’s learning will go. But in any case changes need to be made.

For the mother of two from Puebla, it may just be a case of adapting to a new rhythm for her children to catch up and succeed. ‘Children and young people affected by education during the pandemic will have to adapt themselves to the new goals of the government,’ she explained. ‘As parents, we will have to re-evaluate how much time we dedicate to our children at home [given that they will need more support to catch up].’ For Juan Martín Pérez García, intergenerational dialogues that bring children onboard in decision-making will be crucial for the future. He recognized how much damage has been done to them during the pandemic and suggested the best solutions will arise when children are considered as subjects with agency.

Main image: from YouTube video posted by El Universal