Many Morales supporters, however, are conflicted. “Most people in El Alto support MAS [Morales’ Movement to Socialism party]. In La Paz there’s support for him too, but he lost a lot of middle class support during the crackdown on the highway protestors,” says Alejandra, referring to one of the president’s most controversial policies, the proposed Villa Tunari-San Ignacio de Moxos Highway. The Brazilian-funded project, which would link the Brazilian Amazon with the Pacific coast through the Isiboro Sécure National Park and Indigenous Territory (TIPNIS), provoked fierce and widespread protests in 2011.

Civil liberties are another concern. One European NGO worker based in Bolivia for several years praises Morales’ socio-economic programmes, but warns freedoms are under threat. “Before Evo Morales was elected there was a kind of apartheid between the white political elite and the indigenous communities,” she says. “He’s helped to change that. And his nationalisation of the oil and electricity companies – everyone said the foreign companies would pull out, but they didn’t.

“But he has so much power now. There’s no effective opposition. One foreign NGO had to leave last year because it was supposedly ‘supporting subversive elements’. We’ve had to change what we do, and I’ve even gone through my own Facebook wall deleting things [that could be deemed controversial].”

In the far southwest of Bolivia – a stark landscape of salt flats, mountains and extensive lithium reserves – infrastructure projects have had a big impact, notably a new road that slashed in half journey times between the remote tourist hub of Uyuni and the city of Potosí.

However, there are also worries. Alvaro, a 31-year-old tour guide in Uyuni and a MAS supporter, references Morales’ 2008 referendum victory, which changed the constitution and allowed him to serve a third presidential term. “Evo did some good things – the roads, the schools,” he says. “He will win the election, but he’s breaking his promise. He said he would on serve two terms, as the constitution said. But he’s changed the law now. You can stay in power for too long. Change is good.”

This sentiment is most commonly aired in eastern Bolivia. The region is dominated by Santa Cruz de la Sierra, the country economic powerhouse and long a seat of opposition to Morales. At various points the tropical city, wealthy off the back of extensive petro-carbon and agricultural development, has attempted to secede. But Morales’ adroit political manoeuvring has helped to dissipate this hostility in recent years.

But while Santa Cruz may not be in open revolt against Morales, opposition isn’t hard to find. At a restaurant set around a lush courtyard garden populated with hummingbirds, Teresa outlines a common attitude. “Nobody likes Evo here,” says the young businesswoman. “It’s like Catalonia – everybody here wants independence. We do all the work, make all the money. But it won’t happen, we’re too important to the country. We feel different here. Anyway it doesn’t matter, Evo will win of course.”

On this last point, at least, Morales is in agreement – indeed, he is already looking beyond the election. After completing his third term as president, he told reporters recently, he plans to set-up a barbecue restaurant.

Shafik Meghji co-authors The Rough Guide to Bolivia and is a LAB trustee

www.shafikmeghji.com

@ShafikMeghji

Many Morales supporters, however, are conflicted. “Most people in El Alto support MAS [Morales’ Movement to Socialism party]. In La Paz there’s support for him too, but he lost a lot of middle class support during the crackdown on the highway protestors,” says Alejandra, referring to one of the president’s most controversial policies, the proposed Villa Tunari-San Ignacio de Moxos Highway. The Brazilian-funded project, which would link the Brazilian Amazon with the Pacific coast through the Isiboro Sécure National Park and Indigenous Territory (TIPNIS), provoked fierce and widespread protests in 2011.

Civil liberties are another concern. One European NGO worker based in Bolivia for several years praises Morales’ socio-economic programmes, but warns freedoms are under threat. “Before Evo Morales was elected there was a kind of apartheid between the white political elite and the indigenous communities,” she says. “He’s helped to change that. And his nationalisation of the oil and electricity companies – everyone said the foreign companies would pull out, but they didn’t.

“But he has so much power now. There’s no effective opposition. One foreign NGO had to leave last year because it was supposedly ‘supporting subversive elements’. We’ve had to change what we do, and I’ve even gone through my own Facebook wall deleting things [that could be deemed controversial].”

In the far southwest of Bolivia – a stark landscape of salt flats, mountains and extensive lithium reserves – infrastructure projects have had a big impact, notably a new road that slashed in half journey times between the remote tourist hub of Uyuni and the city of Potosí.

However, there are also worries. Alvaro, a 31-year-old tour guide in Uyuni and a MAS supporter, references Morales’ 2008 referendum victory, which changed the constitution and allowed him to serve a third presidential term. “Evo did some good things – the roads, the schools,” he says. “He will win the election, but he’s breaking his promise. He said he would on serve two terms, as the constitution said. But he’s changed the law now. You can stay in power for too long. Change is good.”

This sentiment is most commonly aired in eastern Bolivia. The region is dominated by Santa Cruz de la Sierra, the country economic powerhouse and long a seat of opposition to Morales. At various points the tropical city, wealthy off the back of extensive petro-carbon and agricultural development, has attempted to secede. But Morales’ adroit political manoeuvring has helped to dissipate this hostility in recent years.

But while Santa Cruz may not be in open revolt against Morales, opposition isn’t hard to find. At a restaurant set around a lush courtyard garden populated with hummingbirds, Teresa outlines a common attitude. “Nobody likes Evo here,” says the young businesswoman. “It’s like Catalonia – everybody here wants independence. We do all the work, make all the money. But it won’t happen, we’re too important to the country. We feel different here. Anyway it doesn’t matter, Evo will win of course.”

On this last point, at least, Morales is in agreement – indeed, he is already looking beyond the election. After completing his third term as president, he told reporters recently, he plans to set-up a barbecue restaurant.

Shafik Meghji co-authors The Rough Guide to Bolivia and is a LAB trustee

www.shafikmeghji.com

@ShafikMeghji

Bolivia: Evo set to win amidst a mix of hope and fear

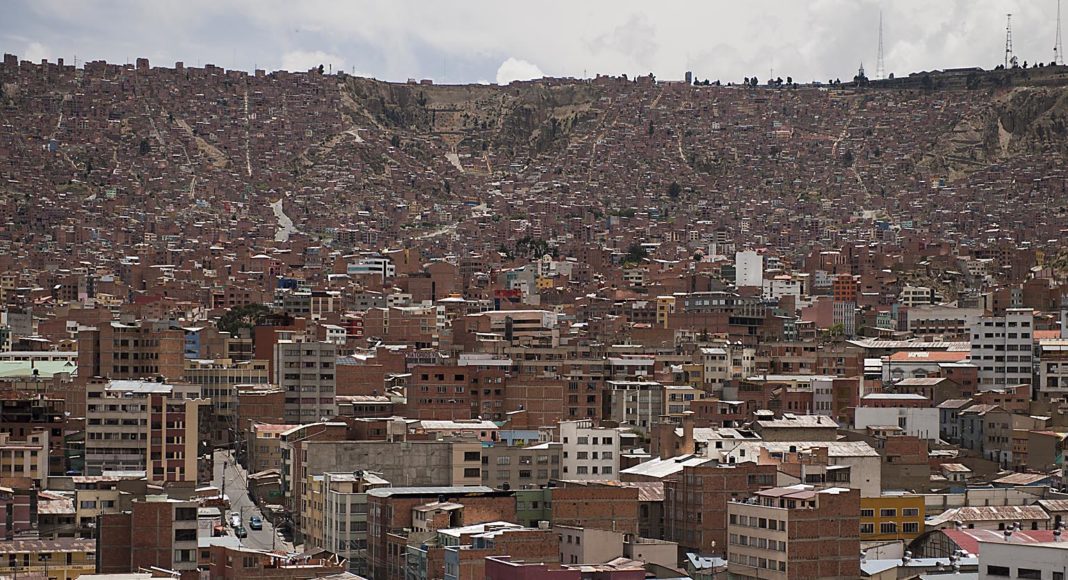

“My city is changing.” “Thieves will be burned.” “Vote Evo Morales”. The graffiti on the walls of El Alto, the city that sprawls above the Bolivian capital of La Paz, reveal a potent mix of hope and fear.

“People migrated from the countryside to find better opportunities in La Paz, stopped off here as it was cheaper, and built their own houses,” says Alejandra, a 21-year-old student. “Before that there was nothing in El Alto. Now it’s the second biggest city in Bolivia, after Santa Cruz, and the Aymara capital of the world: 90 per cent of people here speak Aymara, though really in Bolivia we are all mestizos. El Alto and La Paz are so connected: people from La Paz work in El Alto’s factories, the people of El Alto work in La Paz’s public institutions. But there are still racist views of El Alto, that it is dirty, chaotic, dangerous.”

Over the last decade El Alto, Bolivia’s youngest and fastest growing city, has played an increasingly important political role. The protests that forced President Gonzalo Sánchez – popularly known as “Goni” – to flee Bolivia in a helicopter in 2003 started here, and support from Alteños helped to propel Evo Morales to power in 2005 and 2009.

Bolivia goes to the polls again on 12 October with Morales, Bolivia’s first indigenous president, set for another landslide. A mid-September survey had him on 54 per cent, with his nearest rival, Samuel Doria of the Democratic Union party, trailing behind on just 17 per cent. A recent UN report noted a 32 per cent drop in poverty in Bolivia in the decade to 2012, the biggest fall in South America. Growth rates, meanwhile, are among the highest on the continent.

Many Morales supporters, however, are conflicted. “Most people in El Alto support MAS [Morales’ Movement to Socialism party]. In La Paz there’s support for him too, but he lost a lot of middle class support during the crackdown on the highway protestors,” says Alejandra, referring to one of the president’s most controversial policies, the proposed Villa Tunari-San Ignacio de Moxos Highway. The Brazilian-funded project, which would link the Brazilian Amazon with the Pacific coast through the Isiboro Sécure National Park and Indigenous Territory (TIPNIS), provoked fierce and widespread protests in 2011.

Civil liberties are another concern. One European NGO worker based in Bolivia for several years praises Morales’ socio-economic programmes, but warns freedoms are under threat. “Before Evo Morales was elected there was a kind of apartheid between the white political elite and the indigenous communities,” she says. “He’s helped to change that. And his nationalisation of the oil and electricity companies – everyone said the foreign companies would pull out, but they didn’t.

“But he has so much power now. There’s no effective opposition. One foreign NGO had to leave last year because it was supposedly ‘supporting subversive elements’. We’ve had to change what we do, and I’ve even gone through my own Facebook wall deleting things [that could be deemed controversial].”

In the far southwest of Bolivia – a stark landscape of salt flats, mountains and extensive lithium reserves – infrastructure projects have had a big impact, notably a new road that slashed in half journey times between the remote tourist hub of Uyuni and the city of Potosí.

However, there are also worries. Alvaro, a 31-year-old tour guide in Uyuni and a MAS supporter, references Morales’ 2008 referendum victory, which changed the constitution and allowed him to serve a third presidential term. “Evo did some good things – the roads, the schools,” he says. “He will win the election, but he’s breaking his promise. He said he would on serve two terms, as the constitution said. But he’s changed the law now. You can stay in power for too long. Change is good.”

This sentiment is most commonly aired in eastern Bolivia. The region is dominated by Santa Cruz de la Sierra, the country economic powerhouse and long a seat of opposition to Morales. At various points the tropical city, wealthy off the back of extensive petro-carbon and agricultural development, has attempted to secede. But Morales’ adroit political manoeuvring has helped to dissipate this hostility in recent years.

But while Santa Cruz may not be in open revolt against Morales, opposition isn’t hard to find. At a restaurant set around a lush courtyard garden populated with hummingbirds, Teresa outlines a common attitude. “Nobody likes Evo here,” says the young businesswoman. “It’s like Catalonia – everybody here wants independence. We do all the work, make all the money. But it won’t happen, we’re too important to the country. We feel different here. Anyway it doesn’t matter, Evo will win of course.”

On this last point, at least, Morales is in agreement – indeed, he is already looking beyond the election. After completing his third term as president, he told reporters recently, he plans to set-up a barbecue restaurant.

Shafik Meghji co-authors The Rough Guide to Bolivia and is a LAB trustee

www.shafikmeghji.com

@ShafikMeghji

Many Morales supporters, however, are conflicted. “Most people in El Alto support MAS [Morales’ Movement to Socialism party]. In La Paz there’s support for him too, but he lost a lot of middle class support during the crackdown on the highway protestors,” says Alejandra, referring to one of the president’s most controversial policies, the proposed Villa Tunari-San Ignacio de Moxos Highway. The Brazilian-funded project, which would link the Brazilian Amazon with the Pacific coast through the Isiboro Sécure National Park and Indigenous Territory (TIPNIS), provoked fierce and widespread protests in 2011.

Civil liberties are another concern. One European NGO worker based in Bolivia for several years praises Morales’ socio-economic programmes, but warns freedoms are under threat. “Before Evo Morales was elected there was a kind of apartheid between the white political elite and the indigenous communities,” she says. “He’s helped to change that. And his nationalisation of the oil and electricity companies – everyone said the foreign companies would pull out, but they didn’t.

“But he has so much power now. There’s no effective opposition. One foreign NGO had to leave last year because it was supposedly ‘supporting subversive elements’. We’ve had to change what we do, and I’ve even gone through my own Facebook wall deleting things [that could be deemed controversial].”

In the far southwest of Bolivia – a stark landscape of salt flats, mountains and extensive lithium reserves – infrastructure projects have had a big impact, notably a new road that slashed in half journey times between the remote tourist hub of Uyuni and the city of Potosí.

However, there are also worries. Alvaro, a 31-year-old tour guide in Uyuni and a MAS supporter, references Morales’ 2008 referendum victory, which changed the constitution and allowed him to serve a third presidential term. “Evo did some good things – the roads, the schools,” he says. “He will win the election, but he’s breaking his promise. He said he would on serve two terms, as the constitution said. But he’s changed the law now. You can stay in power for too long. Change is good.”

This sentiment is most commonly aired in eastern Bolivia. The region is dominated by Santa Cruz de la Sierra, the country economic powerhouse and long a seat of opposition to Morales. At various points the tropical city, wealthy off the back of extensive petro-carbon and agricultural development, has attempted to secede. But Morales’ adroit political manoeuvring has helped to dissipate this hostility in recent years.

But while Santa Cruz may not be in open revolt against Morales, opposition isn’t hard to find. At a restaurant set around a lush courtyard garden populated with hummingbirds, Teresa outlines a common attitude. “Nobody likes Evo here,” says the young businesswoman. “It’s like Catalonia – everybody here wants independence. We do all the work, make all the money. But it won’t happen, we’re too important to the country. We feel different here. Anyway it doesn’t matter, Evo will win of course.”

On this last point, at least, Morales is in agreement – indeed, he is already looking beyond the election. After completing his third term as president, he told reporters recently, he plans to set-up a barbecue restaurant.

Shafik Meghji co-authors The Rough Guide to Bolivia and is a LAB trustee

www.shafikmeghji.com

@ShafikMeghji

Many Morales supporters, however, are conflicted. “Most people in El Alto support MAS [Morales’ Movement to Socialism party]. In La Paz there’s support for him too, but he lost a lot of middle class support during the crackdown on the highway protestors,” says Alejandra, referring to one of the president’s most controversial policies, the proposed Villa Tunari-San Ignacio de Moxos Highway. The Brazilian-funded project, which would link the Brazilian Amazon with the Pacific coast through the Isiboro Sécure National Park and Indigenous Territory (TIPNIS), provoked fierce and widespread protests in 2011.

Civil liberties are another concern. One European NGO worker based in Bolivia for several years praises Morales’ socio-economic programmes, but warns freedoms are under threat. “Before Evo Morales was elected there was a kind of apartheid between the white political elite and the indigenous communities,” she says. “He’s helped to change that. And his nationalisation of the oil and electricity companies – everyone said the foreign companies would pull out, but they didn’t.

“But he has so much power now. There’s no effective opposition. One foreign NGO had to leave last year because it was supposedly ‘supporting subversive elements’. We’ve had to change what we do, and I’ve even gone through my own Facebook wall deleting things [that could be deemed controversial].”

In the far southwest of Bolivia – a stark landscape of salt flats, mountains and extensive lithium reserves – infrastructure projects have had a big impact, notably a new road that slashed in half journey times between the remote tourist hub of Uyuni and the city of Potosí.

However, there are also worries. Alvaro, a 31-year-old tour guide in Uyuni and a MAS supporter, references Morales’ 2008 referendum victory, which changed the constitution and allowed him to serve a third presidential term. “Evo did some good things – the roads, the schools,” he says. “He will win the election, but he’s breaking his promise. He said he would on serve two terms, as the constitution said. But he’s changed the law now. You can stay in power for too long. Change is good.”

This sentiment is most commonly aired in eastern Bolivia. The region is dominated by Santa Cruz de la Sierra, the country economic powerhouse and long a seat of opposition to Morales. At various points the tropical city, wealthy off the back of extensive petro-carbon and agricultural development, has attempted to secede. But Morales’ adroit political manoeuvring has helped to dissipate this hostility in recent years.

But while Santa Cruz may not be in open revolt against Morales, opposition isn’t hard to find. At a restaurant set around a lush courtyard garden populated with hummingbirds, Teresa outlines a common attitude. “Nobody likes Evo here,” says the young businesswoman. “It’s like Catalonia – everybody here wants independence. We do all the work, make all the money. But it won’t happen, we’re too important to the country. We feel different here. Anyway it doesn’t matter, Evo will win of course.”

On this last point, at least, Morales is in agreement – indeed, he is already looking beyond the election. After completing his third term as president, he told reporters recently, he plans to set-up a barbecue restaurant.

Shafik Meghji co-authors The Rough Guide to Bolivia and is a LAB trustee

www.shafikmeghji.com

@ShafikMeghji

Many Morales supporters, however, are conflicted. “Most people in El Alto support MAS [Morales’ Movement to Socialism party]. In La Paz there’s support for him too, but he lost a lot of middle class support during the crackdown on the highway protestors,” says Alejandra, referring to one of the president’s most controversial policies, the proposed Villa Tunari-San Ignacio de Moxos Highway. The Brazilian-funded project, which would link the Brazilian Amazon with the Pacific coast through the Isiboro Sécure National Park and Indigenous Territory (TIPNIS), provoked fierce and widespread protests in 2011.

Civil liberties are another concern. One European NGO worker based in Bolivia for several years praises Morales’ socio-economic programmes, but warns freedoms are under threat. “Before Evo Morales was elected there was a kind of apartheid between the white political elite and the indigenous communities,” she says. “He’s helped to change that. And his nationalisation of the oil and electricity companies – everyone said the foreign companies would pull out, but they didn’t.

“But he has so much power now. There’s no effective opposition. One foreign NGO had to leave last year because it was supposedly ‘supporting subversive elements’. We’ve had to change what we do, and I’ve even gone through my own Facebook wall deleting things [that could be deemed controversial].”

In the far southwest of Bolivia – a stark landscape of salt flats, mountains and extensive lithium reserves – infrastructure projects have had a big impact, notably a new road that slashed in half journey times between the remote tourist hub of Uyuni and the city of Potosí.

However, there are also worries. Alvaro, a 31-year-old tour guide in Uyuni and a MAS supporter, references Morales’ 2008 referendum victory, which changed the constitution and allowed him to serve a third presidential term. “Evo did some good things – the roads, the schools,” he says. “He will win the election, but he’s breaking his promise. He said he would on serve two terms, as the constitution said. But he’s changed the law now. You can stay in power for too long. Change is good.”

This sentiment is most commonly aired in eastern Bolivia. The region is dominated by Santa Cruz de la Sierra, the country economic powerhouse and long a seat of opposition to Morales. At various points the tropical city, wealthy off the back of extensive petro-carbon and agricultural development, has attempted to secede. But Morales’ adroit political manoeuvring has helped to dissipate this hostility in recent years.

But while Santa Cruz may not be in open revolt against Morales, opposition isn’t hard to find. At a restaurant set around a lush courtyard garden populated with hummingbirds, Teresa outlines a common attitude. “Nobody likes Evo here,” says the young businesswoman. “It’s like Catalonia – everybody here wants independence. We do all the work, make all the money. But it won’t happen, we’re too important to the country. We feel different here. Anyway it doesn’t matter, Evo will win of course.”

On this last point, at least, Morales is in agreement – indeed, he is already looking beyond the election. After completing his third term as president, he told reporters recently, he plans to set-up a barbecue restaurant.

Shafik Meghji co-authors The Rough Guide to Bolivia and is a LAB trustee

www.shafikmeghji.com

@ShafikMeghji