Amnesty International has just released a report called No me Borren de la Historia: Verdad, Justicia y Reparación (1964-1982 (Don’t Erase Me from History: Truth, Justice and Reparation in Bolivia (1964-1982). The document, which is yet to be translated into English, details the Bolivian government’s failure to investigate incidents of abduction, assassination and torture committed by the state during the military dictatorships of the mid-twentieth century.

Amnesty International has just released a report called No me Borren de la Historia: Verdad, Justicia y Reparación (1964-1982 (Don’t Erase Me from History: Truth, Justice and Reparation in Bolivia (1964-1982). The document, which is yet to be translated into English, details the Bolivian government’s failure to investigate incidents of abduction, assassination and torture committed by the state during the military dictatorships of the mid-twentieth century.As it was for the region in general, the twentieth century was a time of violent instability in Bolivia, greatly exacerbated by the Cold War manoeuvrings of the United States. Under Plan Cóndor, the CIA colluded with rightwing juntas throughout the region, facilitating the systematic crushing of leftist political movements with a clandestine campaign of terror and persecution that saw thousands declared missing.

Bolivia’s 18 years of dictatorship ended in 1982 after General Luis García Meza — infamous for his regime’s links to drug cartels, European neo-fascists and Nazi war criminals — was forced to step down. Meza’s fall eventually led to the return of democracy to Bolivia, and in 2003 (after another two decades of intense instability) Evo Morales, its first indigenous president, was elected.

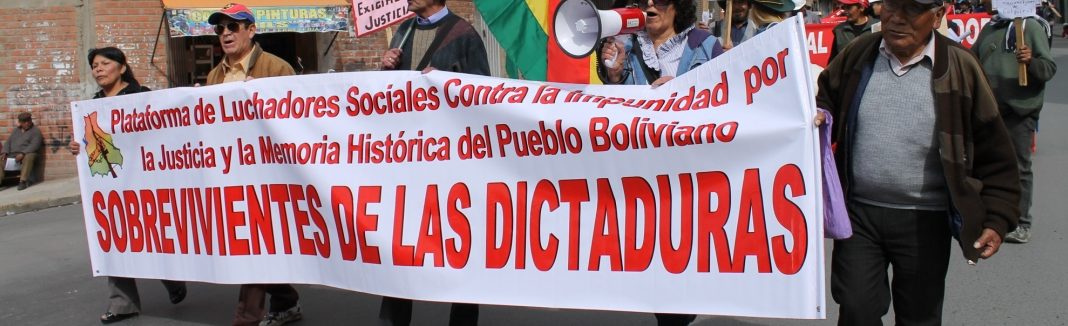

Despite the wide-ranging changes the Morales government has brought to Bolivia, the country is still undergoing the difficult process of coming to terms with the violence of its recent past. While countries like Chile and Argentina have set up public investigations into the use of torture and assassination in this era, Amnesty’s report highlights the Bolivian government’s failure to live up to this responsibility.

Although Meza is now serving a 30-year prison sentence, the government has not yet opened its military archives to public investigation nor made good on its promise to support victims of torture and the families of those who were murdered. In 2004 Law 2640 was passed, forcing the government to offer financial aid and healthcare to the victims of these crimes, but, as the Amnesty report recognises, out of the 6,200 people who applied for support only 1,714 have received any kind of help.

Law 2640’s ineptitude surprised few of the activists who have been campaigning for support and recognition. From the outset the process was fraught with a mixture of bureaucratic incompetence and political complacency. Applicants were even asked to provide proof of the abuses they suffered from the institutions responsible for their torture, which effectively forced victims of rape to gain confessions from the authorities that facilitated their attacks.

Victoria López, an ex-union leader who says her torture during the Meza regime caused her to have a miscarriage, is now a key figure in the struggle for recognition by the victims and their families. For the last two years, along with her fellow activists, she has been living in a makeshift tent outside the Ministry of Justice in central La Paz. In February 2013 she was attacked by a group of men who broke into the tent and beat her up, causing serious damage to her head and breaking one of her arms. Earlier this year she also survived an arson attack on the tent.

“We’re not fighting for a cash payment, which would be humiliating, no,” Victoria told me during an interview in La Paz last year, “We fight for our dignity, for our family, for the people whose human rights were violated. We fight to prevent these things from happening again. What will happen to youngsters who are the children of democracy? They have to remember these crimes so that this never happens again.”

The Amnesty report recognises the need for widespread cultural recognition in Bolivia of the abuses of the past, stating that “What happened in these years can’t be forgotten completely, nor can it go unpunished. It is a burden on the Bolivian State as it is principally responsible for what has happened. In this regard it’s imperative that the truth about these events is brought to public attention.”

Many of the activists I spoke to in La Paz pointed to the example of Chile as a country that has taken great steps to foster a culture of understanding and education with regards to Pinochet’s crimes. Santiago’s Museum of Memory and Human Rights is respected as one of the region’s finest museums and is an important symbol for a country trying to understand its recent past. In Bolivia there’s no comparable institution yet, but the small makeshift tent on El Prado, inhabited by those who have already been through so much, may yet set the foundations for such a monument.

*Cioran is a writer and filmmaker. In 2012 he and Lisa Burdof-Sick made a documentary about the legacy of the dictatorships. ‘Ni Olvido, Ni Perdón, Justicia’ was the result of a collaboration with ITEI, a Bolivian NGO based in La Paz that researches human rights abuses in the country while offering medical, psychological and legal aid to victims of torture.

For more information about the documentary, click here.

For more information about ITEI, click here

Cioran blogs at Calle Nine.

Big photo credit: Gonzalo Ordoñez for the Andean Information Centre.