Update. At the time these articles were written, the Bolivian govermnent had insisted that it would go ahead with the highway. Now, President Morales has decided to suspend its construction. On Sunday 25 September, protesters clashed with the police and hundreds of people were injured and arrested. Defence Minister María Cecilia Chacón resigned in protest for the violent repression against the protesters. Hours later, Interior Minister Sacha Llorenti resigned after he was severely criticised for his handling of the crisis. Protests, however, continue. For regular updates from Dario, please click here .

By Dario Kenner*, La Paz

The controversy causing shockwaves at home and abroad is the plan by the government to build a highway through the middle of a national park that is also a recognised autonomous indigenous territory called TIPNIS (Isiboro Sécure National Park and Indigenous Territory).

[The first part of this article summarises the TIPNIS conflict to date. The second part goes into more detail on the Government Position (Accusations against the United States and NGOs) and the Marcher Position (Demands, Attitude of Morales government). The third part deals with the underlying issues: Consultation, Land distribution, Coca and Regional Integration – IIRSA]

The key issue

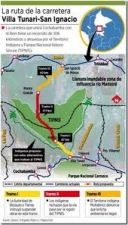

Route of highwayThe indigenous social movements have made it clear they are not against the plan to build a highway to link the regions of Cochabamba and Beni. What they are protesting about is that the Bolivian government have not done prior consultation and that the planned highway would go right through the middle of their territory of just over a million hectares – territory that was handed over to them by President Morales in 2009.

Route of highwayThe indigenous social movements have made it clear they are not against the plan to build a highway to link the regions of Cochabamba and Beni. What they are protesting about is that the Bolivian government have not done prior consultation and that the planned highway would go right through the middle of their territory of just over a million hectares – territory that was handed over to them by President Morales in 2009.

As the map shows the current planned route of the highway would go directly through the virtually untouched nucleus of the national park which is an area of exceptional biodiversity. There are over 700 species of fauna and 400 species of flora, and the forests in the park play a crucial role in regulating water cycles and the climate. A study estimates that64% of the national park would be lost within 18 years if the road is built .

The curious thing is that if the government were to change the route of the highway so that it did not go through the TIPNIS, the march would stop. The question that everyone is asking is: why does the highway have to go along that specific route? So far nobody knows for sure, but the rumour goes that there is oil inside TIPNIS.

Polarisation across Bolivia

The last four weeks have seen accusation and counter accusation as the Bolivian government and the marchers play a game of cat and mouse which has led to seven failed attempts at dialogue. The government blames the indigenous marchers for refusing to dialogue or for the failure of dialogue when it has briefly begun. Meanwhile the marchers have criticised the attitude of the government and refuse to begin dialogue until work on the highway stops.

March in defense of the TIPNISStatements like this one hardly helped to create the conditions for dialogue. Referring to their being children on the march, Minister of Public Works Walter Delgadillo said, “If they want to sacrifice their children, then they can go to Plaza Murillo [main square in La Paz] and crucify themselves”

March in defense of the TIPNISStatements like this one hardly helped to create the conditions for dialogue. Referring to their being children on the march, Minister of Public Works Walter Delgadillo said, “If they want to sacrifice their children, then they can go to Plaza Murillo [main square in La Paz] and crucify themselves”

What began as a march of around 500 indigenous peoples on 15 August, on a 500+ kilometre route from the Bolivian Amazon to La Paz, has now escalated into a political crisis that is dividing opinion across society. The march now has nearly 1,500 indigenous peoples taking part.

A huge political debate is raging with both sides receiving support from different sectors of society. Local authorities in Cochabamba and populations in towns such as San Ignacio de Moxos in the Amazon want the motorway so they will be better linked up with the rest of the country to sell their products. The cocaleros (coca growers), staunch government allies, also strongly back the highway. Meanwhile the march is receiving support from miners in Oruro and Potosi, indigenous peoples blockading roads in Bolivia´s northern Amazon and the east of the country, and university students in the main cities such as La Paz, Cochabamba and Santa Cruz.

However, what often gets lost in the vitriol are the basic facts of the crisis that the indigenous peoples’ right to be consulted has been violated and that they do not reject the construction of a highway as long as it does not go through the TIPNIS. As the Ombudsman (Defensor del Pueblo) said on 20 September on Radio Erbol, “This is not about intransigence. This is about rights that are clear and have been violated”.

The current situation

Despite the indigenous peoples spending over a month marching, including with children and elderly people (there is a 99 year old marching!), in very difficult conditions and without proper supplies it is clear they are determined to reach an agreement that they feel will defend their rights and territory. For them this means the highway not going through the TIPNIS. It is surprising the Bolivian government has let the conflict go on this long because each day the issue generates more controversy which includes international petitions.

There are potential solutions such as changing the route of the highway, but so far the government refuses to budge. If the march gets to La Paz it is likely it would get support from people in the city, who have already held marches in solidarity with the indigenous peoples, and this is exactly why the Morales government does not want the march to get to La Paz and is doing all it can to prevent this happening. Social movements allied with the government like the coca growers (cocaleros) could also make an appearance.

Will the march get to La Paz?

Police block the march from advancing to La PazThere are still over 250 kilometresto go out of the total 500+ kilometres. There is currently a highly tense standoff due to a blockade which has been set up in Yucumo and the presence of 400 police who are stopping the marchers from advancing. An important rural social movement, the Confederation of Intercultural Communities of Bolivia (CSCIB), have been blockading in support of the highway and to demand the removal of five of the marcher’s demands (see full set of demands in part 2) and that the marchers dialogue with the government. This last point does not make sense because the very aim of the march is to get to La Paz and dialogue with the government. Everyone is praying there will not be any violent clashes, but the members of CSCIB who have been maintaining this blockade in Yucumo for over two weeks have threatened to stop the march from progressing – even though the indigenous march is peaceful and is not obstructing the road.

Police block the march from advancing to La PazThere are still over 250 kilometresto go out of the total 500+ kilometres. There is currently a highly tense standoff due to a blockade which has been set up in Yucumo and the presence of 400 police who are stopping the marchers from advancing. An important rural social movement, the Confederation of Intercultural Communities of Bolivia (CSCIB), have been blockading in support of the highway and to demand the removal of five of the marcher’s demands (see full set of demands in part 2) and that the marchers dialogue with the government. This last point does not make sense because the very aim of the march is to get to La Paz and dialogue with the government. Everyone is praying there will not be any violent clashes, but the members of CSCIB who have been maintaining this blockade in Yucumo for over two weeks have threatened to stop the march from progressing – even though the indigenous march is peaceful and is not obstructing the road.

It is also unclear what the role of the 400 police deployed by the government is. Are they there to prevent clashes between the CSCIB and the march? Or are they blocking the route for the march to pass as the indigenous peoples claim? It is strange that the police have not removed the Yucumo blockade (which supports the government position) and yet have quickly moved to end two blockades in the Santa Cruz region by the Ayorero and Guarani peoples in support of the TIPNIS march. The police used tear gas on both occasions, resulting in injuries. The Ombudsman has publicly stated that both the Yucumo blockade and the police preventing the passage of the march go against the Bolivian Constitution which guarantees freedom of movement.

If there were any deaths or injuries in clashes it would lead to a major escalation of the TIPNIS conflict and engulf the country in a deep political crisis with unpredictable consequences for both the MAS government and the process of change.

* Udpates on Bolivia on Twitter: @dariokenner