Right of indigenous peoples to consultation, Mother Earth and the need to “develop”, Unequal land distribution, Coca, and Regional Integration (IIRSA).

By Dario Kenner, La Paz

Right of indigenous peoples to consultation

The MAS government has already violated the right of the indigenous communities living in TIPNIS to be consulted because any consultation on a project that will affect an indigenous territory must be done before the project begins. This is not an option for the MAS government it is an obligation. Bolivia has ratified the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and International Labour Organisation Convention 169. Both these pieces of international legislation and the Bolivian Constitution approved in 2009 clearly state that indigenous peoples have the right to prior consultation and in good faith (Bolivian Constitution articles 30, 343, 352: UNDRIP articles 19 and 32: ILO 169 article 6).

The Bolivian government claims the project has not begun inside the indigenous territory of TIPNIS because the highway project is split into three sections (the second section supposedly goes through TIPNIS). However, this is not true because the contract with the Brazilian company OAS building the motorway (available here in Spanish) does not refer to three sections, therefore once work has begun on any part of the highway it means it has begun on all of the highway. In addition there is already evidence that work has begun on the highway inside of TIPNIS. This means the Bolivian government has not only violated the right to prior consultation but also the right of indigenous peoples to decide on development projects within their territories (UNDRIP articles 18 and 23: ILO 169 article 7).

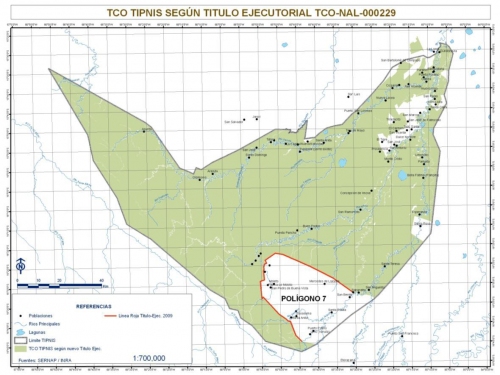

TIPNIS national park. White areas have been deforested. The area in the south has been occupied by coca growers and is no longer part of the official indigenous autonomous territory: Bolivian Agency for Protected Areas (SERNAP) August 2011

TIPNIS national park. White areas have been deforested. The area in the south has been occupied by coca growers and is no longer part of the official indigenous autonomous territory: Bolivian Agency for Protected Areas (SERNAP) August 2011

The government is now offering to do the consultation even though it is late. For this to be prior consultation all construction of the highway has to stop. The offer by the government has brought into question who is entitled to be consulted. Legislation clearly states that the only people to be consulted are the indigenous peoples (ILO 169 article 1) and that the consultation must be via their representative institutions (Bolivian Constitution article 30: UNDRIP articles 19 and 32: ILO 169 article 6). In the case of TIPNIS the representative institutions are the TIPNIS Subcentral and Sécure Subcentral that represent the 64 communities living inside the TIPNIS of Yuracaré, Chiman and Moxeño peoples.

The suggestion by the government to also consult the 15,000 coca growing (cocaleros) families who have already occupied the southern part of the TIPNIS national park has been rejected by the marchers who have pointed out it would violate the articles above that state the consultation can only be with the representative indigenous institutions. In fact these 15,000 families are not even inside the official indigenous territory because the area they occupied was separated from the TIPNIS when the land title was handed over in 2009.

Furthermore, on 11 September the government said that any consultation would not be binding –and that there were eight proposals for the route of the highway – all go through TIPNIS.

On 14 September the marchers released a public statement condemning the government for beginning the process of consultation with some of the indigenous communities within the TIPNIS. The marchers made it clear this consultation must be with ALL the 64 communities of the TIPNIS, must be prior to the construction of the highway and must be in good faith. They therefore reject the government’s announcement that it will begin the consultation on 25 September 2011. As the marchers point out, the representative institutions (the TIPNIS Subcentral through which the consultation is meant to be carried out) are marching. So holding a consultation without these institutions being present is illegal.

Further information I wrote about consultation in relation to TIPNIS here in Spanish

TIPNIS national park. White areas have been deforested. The area in the south has been occupied by coca growers and is no longer part of the official indigenous autonomous territory: Bolivian Agency for Protected Areas (SERNAP) August 2011

Coca

For clarification on the difference between coca and cocaine see this article. Critics of the highway (from both left and right) say it would lead to increased occupation of areas of the TIPNIS national park by cocaleros (coca growers). While at the moment this is just a claim, there is already evidence to suggest this could happen. The southern area of the national park has been in a process of occupation by cocaleros since the 1970s (see map above showing area “Poligono 7) and eventually was separated from the official indigenous territory in 2009. This has even led to the forced assimilation of indigenous communities within the occupied area – of those who have remained some now work for the cocaleros. Within this area the main product grown is coca. Given that the planned route of the highway would go through the occupied area and then into the virtually untouched parts of the national park, it can be assumed the cocaleros would use this road.

A report published by the United Nations last week also reveals that whilst the overall level of hectares used to produce coca in Bolivia has remained stable the percentage has gone up inside the TIPNIS national park by 9% compared with 2009.

Mother Earth and the need to “develop”

Map of IIRSA focus areas in Latin AmericaThe elections of Bolivia´s first indigenous President Evo Morales in December 2005 brought great expectations of a new social and economic model. This would be difficult to implement in a country with an economy based on extractive industries (as mentioned above) and is not something that would happen in a few years. However, the Morales government, with heavy influence from the Vice President Álvaro García Linera, has pursued a policy of deepening this extractive model to then redistribute resources through social programmes.

Map of IIRSA focus areas in Latin AmericaThe elections of Bolivia´s first indigenous President Evo Morales in December 2005 brought great expectations of a new social and economic model. This would be difficult to implement in a country with an economy based on extractive industries (as mentioned above) and is not something that would happen in a few years. However, the Morales government, with heavy influence from the Vice President Álvaro García Linera, has pursued a policy of deepening this extractive model to then redistribute resources through social programmes.

The difficult question is: will there be a new model of “development” in Bolivia? This is obviously not going to happen instantly, but one indication of the direction of the government is taking is that it has yet to pass a proposal for a Law of Mother Earth that could be the beginning of a transition to a new model. The Guardian reported on this initiative in April 2010. This law would give rights to nature and set in place the duties of the state, private companies and individuals to reduce their impact on the environment. A basic law of the rights of Mother Earth was approved in December 2010 but this full comprehensive law is yet to be passed despite the promise of the government to do so in January 2011, July and again in September.

The feeling of many people here in Bolivia is that the result of this conflict could be defining for the development model implemented in the future. If the march is victorious and the government is forced to change the route of the highway it could mean that the Morales administration would have to respect all other indigenous territories and national parks where there are natural resources to be exploited. Or, if the government is victorious and the highway gets built through TIPNIS, the result could be that all other national parks and indigenous territories would be open to be exploited.

Unequal land distribution – dispute distracts from powerful landowners in the east

On the surface the TIPNIS highway issue is turning into a conflict between some of the important rural social movements, including the cocaleros and the Confederation of Intercultural Communities of Bolivia (CSCIB) who do not identify themselves as indigenous, and self-identified indigenous peoples. However, the real issue is inequality in land distribution and the quality of land. The cocaleros and Intercultural Communities claim that indigenous peoples have been given millions of hectares in collective land titles whilst they, campesinos (broadly translated as small scale farmers and, in the case of the Intercultural communities, Aymara and Quechua migrants from the western highlands), have been given little in comparison. In an interview in May 2010 the former head of the INRA (National Institute for Agrarian Reform) said that between 1996 and 2010 his institution had given land titles of 21 million hectares to the government, 21 million hectares to indigenous territories (TCOs), 6 million hectares as communal titles to campesinos, 2 million hectares to small campesino properties, nearly 2 million to medium sized properties and 1.8 million hectares to agro-industry companies. In this sense the campesinos have cause to complain because in total they received around 8 million hectares compared to the indigenous peoples who received 21 million hectares.

However, just taking these statistics means one forgets that the people who have the most hectares per person and, crucially, the best quality farming land are the big landowners in the east of the country. In 2005 the UNDP estimated that just 100 families owned 25 million hectares of land. I don´t think anyone would deny that campesinos have less land on which to grow their crops, but the real target here should not be the indigenous peoples whose ancestral territories on which they have lived on for centuries have been recognised and given to them. The real target should be the landowners mainly concentrated in the region of Santa Cruz – many of whom were, incidentally, given their land titles illegally by dictators in the 1970s and 1980s.

Regional integration programme promoted by Brazil – IIRSA

Brazil is now the seventh largest economy in the world. The map above shows Brazil´s principal trading routes with China. Brazil can currently get its products to China via the Panama Canal, Cape Horn and Cape of Good Hope. The route that is yet to be fully developed is west of Brazil to the Pacific crossing Bolivia and Peru or Chile. Vice President Álvaro García Linera argues the planned highway connecting Cochabamba and Beni is 300 km from the border with Brazil and is vertical so the project therefore cannot be a transoceanic corridor for Brazil to get its products to the Pacific. However, what he cannot deny is that this project is part of the hundreds of integration projects proposed in the Initiative for the Integration of Regional Infrastructure in South America (IIRSA) since 2000, which is strongly backed by Brazil for the obvious reason that it means Brazil will be better able to exploit natural resources in Latin America and trade with China. In addition the Brazilian state development bank is providing 332 million dollars (80% of the total cost) to fund the highway project.

The other potential interest for Brazil is building the highway along the exact route proposed through the TIPNIS is that there might be oil there. The Minister of Hydrocarbons publicly stated there is oil in TIPNIS on 10 August 2011. The Brazilian state company Petrobras is already very active in Bolivia and there is speculation it might have an agreement with the Bolivian government to explore and exploit this oil. But for the moment we do not know because the Bolivian government keeps on insisting the highway is for the integration and development of Bolivia. There are already many struggles across Latin America against IIRSA and Brazil´s attempts to dominate the region, and some are linking the TIPNIS highway to this regional context.

CONCLUSION

Although the debate has become very politicised it is important to bear in mind that the indigenous peoples of the TIPNIS right to prior consent has not been complied with and this is the why they are marching. Others such as the right-wing media and right wing politicians are taking advantage of the situation and the danger is that the longer the conflict goes on the more they undermine not only the MAS government but also the process of change. The right-wing were politically defeated in the 2009 general elections when the MAS got a two thirds majority in the Plurinational Assembly and Senate. However, they are very vocal and still hold the economic power.

Possible scenarios

Nobody really knows what the outcome of all this will be so I will not try to give any definitive answers. But there are several scenarios that could play out.

• The result of the conflict could define whether or not other national parks and indigenous territories will be opened up for exploitation.

• The indigenous march could stop due to internal divisions or pressure from the government.

• There could be clashes between the indigenous march and other sectors such as cocaleros. If this were to happen the outcomes would be very unpredictable but would be a serious blow to the MAS government.

• Such is the polarisation (and fear of clashes) there could be deep divisions in the popular movement that mobilised between 2000 and 2005 (The Water War, The Gas War etc) and that created the conditions for the MAS to win the 2005 election.

• The march could get to La Paz where people from El Alto and La Paz could join it to form a massive popular protest that would force the Morales government to cave in.

• There was some hope when Foreign Minister David Choquehuanca briefly visited the march to listen to their demands on 13 September. Although he talked about defending Mother Earth he also said the highway had to go through TIPNIS. Broadly speaking he is associated as supporting a position focusing on Mother Earth and indigenous rights. Within the cabinet those who support Vice President Álvaro García Linera take a line based on redistributing income from extractive industries. If the TIPNIS march is victorious it could strengthen the position of Choquehuanca within the cabinet that could then potentially lead to moving away from the dominant García Linera vision.

There are several unanswered questions to reflect on:

Q: Why does the highway have to go along the specific planned route through the middle of the TIPNIS?

Q: Why is the MAS government risking everything over the TIPNIS conflict? This is a conflict that could have been avoided a long time ago by either organising the prior consultation or by changing the route of the highway. Now, after one month, the conflict has exploded and whoever loses (which could be the government) will suffer a major political blow. Why has the MAS government allowed the conflict to escalate and be so protracted?

I welcome comments on the information above. It is difficult to cover such complex issues so briefly.

It would be great to hear what other people have to say about the TIPNIS conflict, about how consultation with indigenous peoples has worked/not worked in other countries, opinions on what all this means for the future of the Bolivian process. Leave your comments at the end of this blog or email me directly: dariokenner at gmail.com