Jim Jones was an American preacher who in 1978 led thousands of his followers to move from the USA to Guyana and then commit mass suicide by drinking cyanide-laced Kool aid.

Main image: An area of illegal deforestation near Apuí, south Amazonas state, taken in August 2020. Image: Bruno Kelly/Amazônia Real.

11 September 2020. Is Bolsonaro a new Jim Jones, encouraging suicidal practices among his followers and actively contributing to Brazil’s 130,000 coronavirus deaths by ignoring science, defying safety rules, handing the administration of the health service to unqualified military officers and now questioning the need for vaccination? His attempt to veto aid and assistance to indigenous peoples has been labelled genocidal, as the number of Covid-19 cases and deaths among them rises steadily.

At the same time, the torching of the Amazon and the Pantanal is not only causing the mass murder of species, but by affecting the local, regional and global climate it is contributing to the ill health and possible death of millions more.

Yet Bolsonaro and his Environment Minister Ricardo Salles are in denial about the scope of the fires now consuming huge areas. Bolsonaro claims fires are part of traditional indigenous and caboclo practices, preparing the land for planting.

A ridiculous explanation, when INPE, the national space research institute, has identified clouds of smoke up to 100 kms long over Altamira and Jacareacanga, in Pará state, and along the highway BR-163. ‘To generate such a dense cloud of smoke, it is not just the burning of a field or a roça (vegetable garden). It has to be the burning of a great deal of organic material and forest’, says INPE researcher Alberto Setzer. In August he described ‘an extensive fire and a huge deforestation happening in the south of Pará, around Novo Progresso. The numbers are great and can be seen by distant satellites, which only capture very intense situations. This shows it is a very large event.’

But for Bolsonaro and his Environment Minister, Ricardo Salles, the ‘Amazon is not burning’.

Fires? I see no fires

Salles’ has republished a video with this title ‘The Amazon is not burning’, prepared by rural producers in Pará ( where 3468 fires have been recorded, compared to 983 last year). The images of pristine forest in it have nothing to do with the Amazon, and even include a mico leao dourado, a monkey species only found in the Atlantic Forest. This is Salles’ only answer to all the images, films, eyewitness accounts and satellite data that show in terrible detail how the Amazon is burning: a fake video.

For the inhabitants of Manaus, shrouded in a thick pall of smoke from forest fires, the Minister’s video is a bad joke. In the first week of September the number of fires increased by 170 per cent in relation to the same period last year. The 2,002 fire hotspots in the state of Amazonas are three times more than in 2019, when 742 were registered by INPE.

This is in spite of the four month ban on fires in the Amazon region announced last month by the government. It is obvious that nobody takes the ban seriously because they know that IBAMA, the Ministry’s enforcement agency for environmental crimes, has been reduced to a toothless tiger, deprived of funding and experienced staff, and prevented from carrying out operations. That role has been handed to the military with funds diverted to the army’s Operação Brasil Verde (Operation Green Brazil). But their results have been pathetic, as the soldiers have no experience of fighting fires or deforestation.

Geographer and environmentalist Carlos Durigan, director of Wildlife Conservation Society Brasil, said, ‘the government took away Ibama’s leadership role in enforcement and passed it to the Ministry of Defence. In practice they are achieving nothing. This can be seen from the low spending of the funds available and the lack of results. The actions are innocuous and fires and deforestation continue to increase.’

For Durigan the government’s Amazon programmes are ineffective because they are based on the military rhetoric of threats to national sovereignty, ‘inspired by the conspiratorial ideology of past decades’. So the National Amazon Council, led by vice president Hamilton Mourão, excludes all representatives of civil society, of academia, and of local governments.

As a result, he says, the abandonment of Brazil’s environmental policy, successfully constructed over the last 20 years, has opened the region to crime: illegal mining, logging, threats to indigenous and local communities, unplanned infrastructure.

Examples of invasions and violence have multiplied in recent weeks. Four young chiquitano indians from Bolivia were shot dead by agents of the Brazilian frontier police GEFRON in Mato Grosso because they had strayed over the border to hunt for game. In Manaus over 50 NGOs and civil society organisations have demanded the suspension of police chiefs after an unknown number of indigenous and riverside inhabitants were killed in the Abacaxis river area during a conflict over invading sports fishermen. Two police agents were also killed.

In Rondonia, one of Funai’s most experienced sertanistas, Riele Franciscato, was killed with an arrow to his heart shot by uncontacted Indians who probably mistook him for one of the invaders now surrounding their territory. Riele died in the noble tradition established by Marshall Candido Rondon, 100 years ago, – ‘Die if need be, but don’t kill’, but his death removed a man who could have played a vital role in assuring the safety of the uncontacted group.

Amazonas – the last frontier

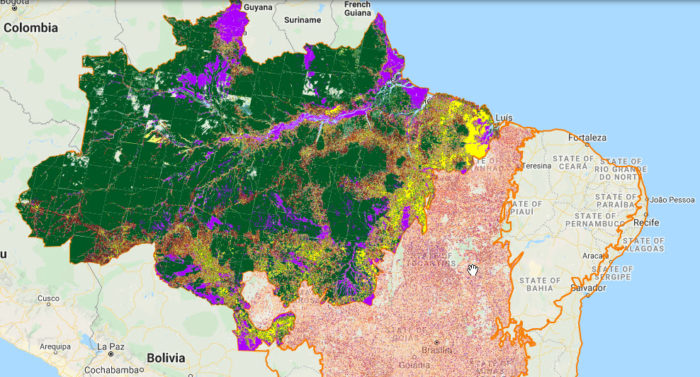

The worrying aspect of this year’s fires is that they show that the state of Amazonas, the largest and up till now most preserved state in the planet’s greatest tropical bioma, has now become part of the agricultural frontier, where landgrabbers, with nothing to fear from the environmental authorities, are targeting public lands, which the government should be designating as conservation units, national forests, sustainable settlements, or indigenous areas.

‘…. Amazonas has become a protagonist in deforestation and fires because people are no longer inhibited from committing environmental crimes,’ according to IPAM director Ane Alencar. ‘When there was more control, they didn’t deforest public areas because they wouldn’t be able to sell the land. But when it becomes obvious that environmental crimes won’t be punished, people begin to think that it’s worth invading public land and selling it, and there will be buyers who think the same way, so that one day soon, this will become normal,’ said IPAM’S director.

Where no rain falls, fire follows

The destruction, and consequent drying out of the Amazon is affecting rainfall in other parts of the country. It is the rios voadores of the Amazon rainforest which bring humidity and rain to the centre and west of Brazil. Much of the Pantanal, the world’s largest tropical wetlands, is suffering the longest drought in 50 years and is on fire. It has already lost 12% of its vegetation to the fires, some of them said to be deliberately set. The great river Paraguai, which runs through the Pantanal, is almost 3 metres below its normal depth, so that navigation of larger boats is impossible. Efforts by firemen, both professional and volunteer, are hopelessly inadequate as the fires fanned by winds sweep across farmland, animal and nature reserves, ecological parks.

Animals die of thirst as they try to escape the fires. News reports show the charred bodies of crocodiles, turtles and snakes stranded in the mud of dried up rivers. A young jaguar with badly burned paws is rescued but does not survive. The refuge of the rare hyacinth macaw, and the sanctuary of the spotted jaguars, are threatened as the fires rage out of control. Instead of a picture of a monkey which lives thousands of miles away, these are the pictures that Salles and his boss, the new Jim Jones, should be showing.