Fernanda Alvarez attended pro-democracy demonstrations in London and spoke to Ali Rocha who attended similar demonstrations in São Paulo calling for ‘no amnesty’ for those who invaded Brazilian Congress and governmental buildings in Brasilia on January 8.

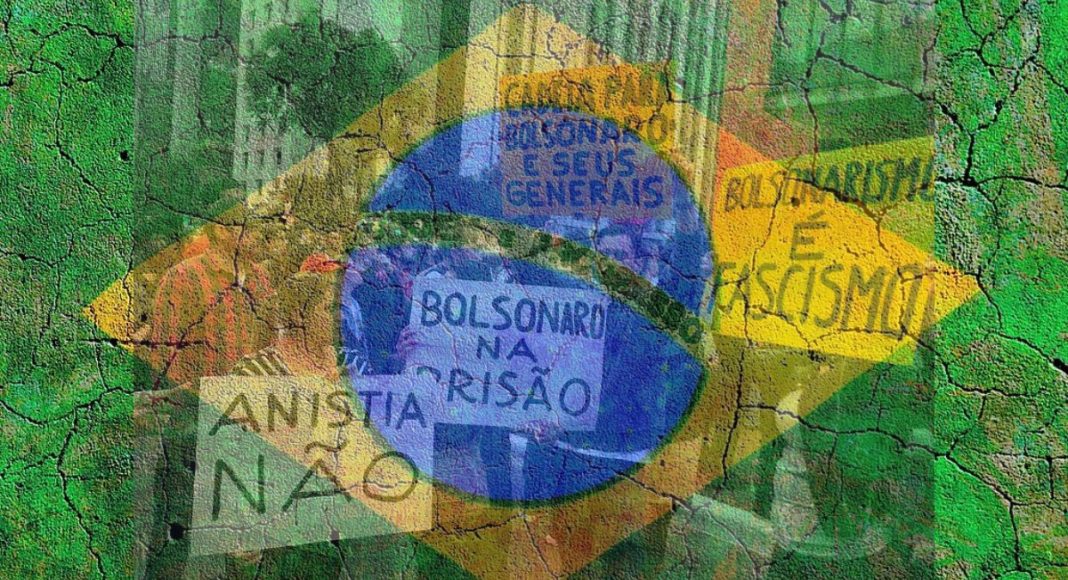

Scenes of broken glass covering the floor of Brazil’s Congress and the mutilated portraits of former Brazilian presidents dominated news coverage last week when Bolsonaristas took Brasilia by storm. The unprecedented attack on Brazilian democracy was, undoubtedly, a sombre reminder that Bolsonarismo continues to be a force to be reckoned with in the country’s politics. However, international backlash against the vandals immediately called for Sem anistia (No amnesty), and a close and critical eye on the invaders’ actions in the media shows that Brazil’s democracy is being publicly defended.

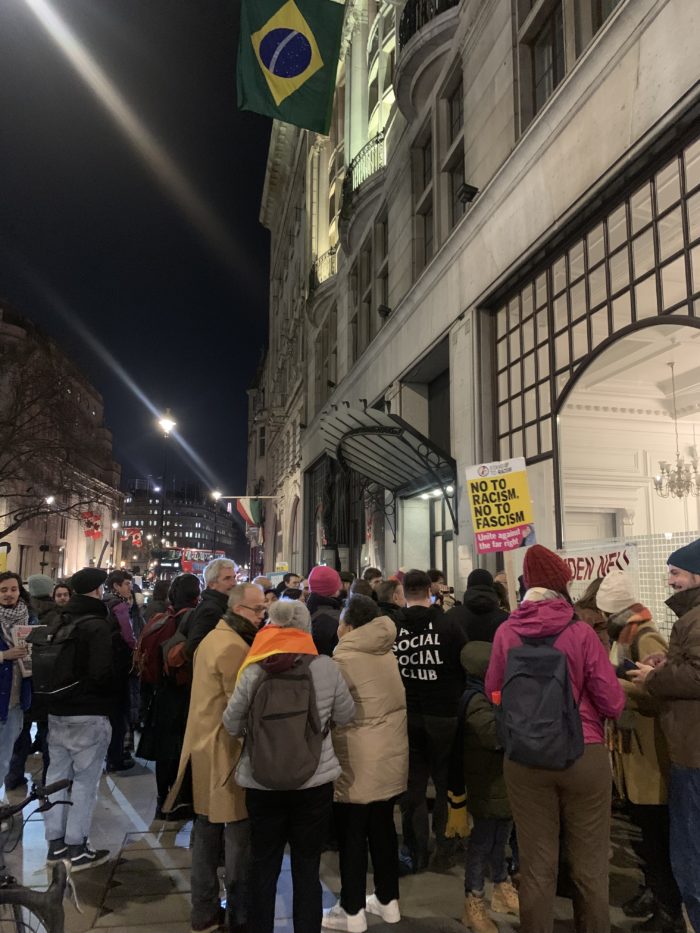

London takes to the streets

In reaction to what justice minister Flavio Dino has already identified as a terrorist attack, Brazilians flocked to the streets of São Paulo, London, New York, and beyond to voice their outrage. In London, protesters braved the winter cold to listen to PT campaigner Elda Cardoso and MP Jeremy Corbyn voice encouraging words that Brazilian democracy will stand strong against Bolsonarismo.

‘Any politician anywhere in the world who dares to speak of redistribution of wealth and power and stand up against those elites and global corporations, is going to face an awful lot of opposition,’ said Corbyn when taking the microphone, and added that ‘the only way to face that opposition is by popular support, that’s why we’re here today, that’s why all over the world people are assembling outside Brazilian embassies saying the same.’

Cardoso shared similar encouraging words in conversation with the Latin America Bureau: ‘We organised this protest to stand in solidarity with the Brazilian people, to show solidarity with the new government in Brazil because democracy is very important all over the world. We cannot accept what we saw happening in Brazil yesterday.’

The insurrection that sent ripples of shock across Brazil shared uncanny similarities to the assault on the US Capitol last year on 6 January. The easily drawn parallels show that, for lack of originality, the insurrectionists relied on a manual of instructions from the USA. In conversation with demonstrators in the crowd in London, the erosion of democracy was a recurrent theme.

Alire Lanes, who was brandishing a cap in support of the Landless Workers Movement, confessed, ‘I’m speechless. I’m still processing everything that’s happening right now. It’s an attack on democracy on a level that we didn’t expect’. Encouragingly, she added, ‘I think everyone should be united because I’m sure that what’s happening in Brazil, on a different level, is happening everywhere.’

The ransacking of Brasilia took place against a tangibly polarized Brazil that very narrowly elected President Lula da Silva in October. Official results from the Supreme Electoral Tribunal crowned Lula winner with 50,9 per cent of the votes, thinly ahead of Bolsonaro’s 49,1 per cent.

For Fernando De Assis, a member of the LGBTQ+ community who has been living in the UK for over 26 years, the insurrection is inexcusable: ‘Seeing someone holding the Brazilian flag and destroying those objects in someone’s name, in the name of Bolsonaro – because it wasn’t in the name of Brazil or in the name of liberty – just because they did not accept the result of the election, is punishable and should not be allowed to be repeated.’

The sentiments of those in London certainly echoed the reactions of the average Brazilian on home soil. According to a Datafolha survey, 93 per cent condemn the attacks in Brasilia and 55 per cent attribute direct responsibility to Bolsonaro. 63 per cent think security forces did less than they should have to stop the invasion and 77 per cent defend prison as a suitable punishment for those who invaded Brasilia. In other words, the statistics mirror the same passionate chants that have defined the character of recent pro-democratic protests, showcasing that fundamentalist, extremist Bolsonarismo does not define Brazil’s attitude towards democracy.

The Frontlines of Brazil’s Pro-Democratic Fight

Across the Atlantic, over 75,000 people took to the streets of São Paulo to stage a pro-democracy demonstration on 9 January. Ali Rocha, a veteran journalist, activist, LAB Correspondent, and founder of Brazil Matters, was one of the thousands of protesters in São Paulo. When commenting on the insurrection and explaining why she protested she said, ‘It’s an attack on democracy. I think an attack on democracy should be raising alarms, especially when we know that it’s part of a wider global movement of the far right.’

While the attack in Brasilia was arguably not surprising considering Bolsonaristas had been camping outside army barracks demanding a military coup, it undoubtedly was unprecedented. Rocha explains, ‘This has never happened in the history of the Brazilian Republic, even during the dictatorship, when they took over power, they never invaded the Three Houses, which are the buildings of the pillars of democracy.’

There are plenty of reasons to remain optimistic about Brazil’s democratic future beyond the demonstrations that have claimed the streets. On the one hand, the Latinobarometro survey shows there’s recently been an improvement in democratic support in Brazil. In 2020, 13.1 per cent of respondents said that in some circumstances an authoritarian government is preferable, down from 15.6 per cent in 2018. Similarly, Datafolha has revealed that 75 per cent of respondents think democracy is the best form of government, up from 70 per cent in 2021.

On the other hand, Brazil’s history is full of examples of relentless mobilization to defend democracy’s corner. The March of the One Hundred Thousand (Passeata dos Cem Mil) saw thousands of students and other sectors of Brazilian society manifesting in 1968 against the military dictatorship.

Subsequently, and with similar chants to those heard last week, the Diretas Já civil unrest movement demanded direct presidential elections in Brazil in 1984. Although the bill failed, the movement served as pressure that helped catalyse the country’s return to democracy a year later. Even Rocha noted that in São Paulo last week ‘people’s response was great, it was great to be there but it felt like history was repeating itself because it felt like when we were calling for direct elections in the 80s and calling for no amnesty.’

Brazil’s deeply entrenched polarization, although not incurable, will continue to represent challenges as Lula’s administration fully retakes the reins of Brazil’s politics. Whilst there’s a lot of damage to figuratively and physically clean up, the immediate reaction that culminated in international and national protests is a reassuring sign that Brazil’s democracy has unbeatable advocates that will continue to protect its integrity.