New lies from old videos

To give a recent example of ‘fake news’: on 15 October the fabricators circulated a video of Haddad stepping out of a yellow Ferrari. The account on which this could be viewed has now been taken down by YouTube ‘due to multiple third-party notifications of copyright infringement’ (see below) Underneath they had inserted a caption, subsequently deleted by YouTube after protests from the PT: ‘The candidate of the poor, arriving yesterday in the airport of Congonhas in São Paulo in a FERRARI that is worth RS$1,800,000 (£370,975)’. Yet the video dates from 2016 when Haddad was mayor of São Paulo and was given a ride in the car to Interlagos, the famous circuit where the Brazilian Grand Prix is held, where he went to inaugurate construction work carried out by his government. Here is the original:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oVsGBiRg5s0

The caption with the faked video was worded to stoke the widespread belief among Bolsonaro followers that, while PT politicians talk the talk of social justice, they are, in reality, are just as corrupt and scandalously wealthy as all other politicians from the Brazilian establishment.

Underneath they had inserted a caption, subsequently deleted by YouTube after protests from the PT: ‘The candidate of the poor, arriving yesterday in the airport of Congonhas in São Paulo in a FERRARI that is worth RS$1,800,000 (£370,975)’. Yet the video dates from 2016 when Haddad was mayor of São Paulo and was given a ride in the car to Interlagos, the famous circuit where the Brazilian Grand Prix is held, where he went to inaugurate construction work carried out by his government. Here is the original:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oVsGBiRg5s0

The caption with the faked video was worded to stoke the widespread belief among Bolsonaro followers that, while PT politicians talk the talk of social justice, they are, in reality, are just as corrupt and scandalously wealthy as all other politicians from the Brazilian establishment.

How far does it reach?

The headline states: ‘Jean Wyllis [one of Brazil’s most famous gay activist] accepts invitation from Haddad to be Minister of Education in an eventual Haddad government’. Except this isn’t true either: this invitation was never made.

The sophistication of this forgery shocked even experienced media professionals. It reproduced accurately the layout in the newspaper and bore the byline of a Globo journalist. Just one problem: the journalist doesn’t work for Globo any more and the headline is fabricated.

This forgery is feeding the prejudice against homosexuals voiced vociferously by Bolsonaro and shared by many of his supporters, and exacerbates the fear that a Haddad victory would lead to homosexuals taking over many key positions in government. A gay Minister of Education is to be particularly feared, for it would mean, they say, that Brazilian children would be encouraged to become gay.

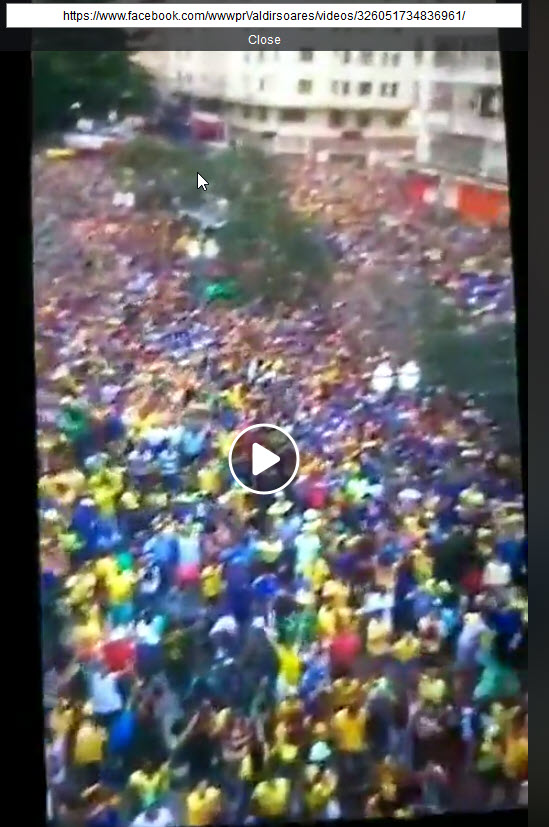

In third place is another video, showing thousands of people in the streets:

The video itself is authentic, but in the version circulating on Facebook, subsequently removed, had the caption: ‘Look how Copacabana is now!!! “Elesim”!!! [“him-yes”, the pro-Bolsonaro slogan thought up as a retort to the anti-Bolsonaro slogan. “Elenão”, “him-no”]’. Except, again, it isn’t. The demo dates from a very different political moment, when there were thousands in the streets in March 2015. Again, the clear intention is to give the impression that pro-Bolsonaro marches have been far bigger than the anti-Bolsonaro ones, though this is not, in fact, the case.

The headline states: ‘Jean Wyllis [one of Brazil’s most famous gay activist] accepts invitation from Haddad to be Minister of Education in an eventual Haddad government’. Except this isn’t true either: this invitation was never made.

The sophistication of this forgery shocked even experienced media professionals. It reproduced accurately the layout in the newspaper and bore the byline of a Globo journalist. Just one problem: the journalist doesn’t work for Globo any more and the headline is fabricated.

This forgery is feeding the prejudice against homosexuals voiced vociferously by Bolsonaro and shared by many of his supporters, and exacerbates the fear that a Haddad victory would lead to homosexuals taking over many key positions in government. A gay Minister of Education is to be particularly feared, for it would mean, they say, that Brazilian children would be encouraged to become gay.

In third place is another video, showing thousands of people in the streets:

The video itself is authentic, but in the version circulating on Facebook, subsequently removed, had the caption: ‘Look how Copacabana is now!!! “Elesim”!!! [“him-yes”, the pro-Bolsonaro slogan thought up as a retort to the anti-Bolsonaro slogan. “Elenão”, “him-no”]’. Except, again, it isn’t. The demo dates from a very different political moment, when there were thousands in the streets in March 2015. Again, the clear intention is to give the impression that pro-Bolsonaro marches have been far bigger than the anti-Bolsonaro ones, though this is not, in fact, the case.

A published ‘fact’ is an established fact

After these findings, Facebook now has third-party fact checkers trying to weed out disinformation. Facebook and Google are also collaborating on an initiative called Comprova, which is working with 24 Brazilian newsrooms to uncover and denounce ‘fake news’. These are important advances but they only scratch at the surface of the problem, and in this world of instant news, a false fact, once published and distributed, is for many readers an established fact. The most influential social networking website in Brazil is WhatsApp (now owned by Facebook). It has a much bigger reach than Facebook, which has been falling in popularity, particularly among the young. And, according to Brazilian data experts, the efforts to clean up Facebook have been encouraging ‘fake news’ fabricators to concentrate more of their efforts on WhatsApp. The volume of false news has been colossal: in the seven weeks before the first round of the election in early October, Agência Lupa, in a joint project with two Brazilian universities, collected and analysed posts in 347 WhatsApp chat groups. This was, they said, “just a small example of the estimated hundreds of thousands of that groups that millions of Brazilians use every day to gather information.” They said that it was particularly difficult to monitor because its conversations are encrypted. From 100,000 political images they selected the 50 most widely shared. Of these, 28 of the 50 most shared images were ‘fake news’, either manipulated or used out of context to give a misleading message. Others had no factual backing. Only four were considered true. The most popular of the 50 images was a black-and-white photo: It claims to be a picture of a young Dilma Rousseff beside a young Fidel Castro. The photo feeds into the allegation, widely made by Bolsonaro supporters, that the PT wants to turn Brazil into a communist state – a fear still very much alive in Brazil, even though there is little evidence to support it.

But, once again, this image is ‘fake news’. The original image (below) was manipulated to include a picture of the young Dilma Rousseff. It dates from 1959, when Dilma Rousseff was only 11 years old:

It claims to be a picture of a young Dilma Rousseff beside a young Fidel Castro. The photo feeds into the allegation, widely made by Bolsonaro supporters, that the PT wants to turn Brazil into a communist state – a fear still very much alive in Brazil, even though there is little evidence to support it.

But, once again, this image is ‘fake news’. The original image (below) was manipulated to include a picture of the young Dilma Rousseff. It dates from 1959, when Dilma Rousseff was only 11 years old:

The militants claimed that Bolsonaro had not been stabbed at all but had invented the incident to garner sympathy from the electorate. But this photo was taken a few hours before the stabbing.

But, as the Agência Lupa studies have repeatedly confirmed, the overwhelming majority of ‘fake news’ items are shared by Bolsonaro supporters.

Some pictures are first published on other platforms and then reproduced on WhatsApp. One of the nastiest was first circulated by Bolsonaro himself to his 1.7 million Twitter followers. He later deleted it. It is a photograph of heavily-armed men behind a placard bearing a death threat to Bolsonaro:

The militants claimed that Bolsonaro had not been stabbed at all but had invented the incident to garner sympathy from the electorate. But this photo was taken a few hours before the stabbing.

But, as the Agência Lupa studies have repeatedly confirmed, the overwhelming majority of ‘fake news’ items are shared by Bolsonaro supporters.

Some pictures are first published on other platforms and then reproduced on WhatsApp. One of the nastiest was first circulated by Bolsonaro himself to his 1.7 million Twitter followers. He later deleted it. It is a photograph of heavily-armed men behind a placard bearing a death threat to Bolsonaro:

Except that the placard was inserted. The original photo dates back to 2016 and is part of a blog about the increase in violence in Brazil. There is no placard:

Except that the placard was inserted. The original photo dates back to 2016 and is part of a blog about the increase in violence in Brazil. There is no placard:

A concerted attack

There is little doubt that the avalanche of ‘fake news’ is affecting the outcome of the election. Unlike the rather disjointed examples of falsified information from the PT, which seems to stem from despair and frustration, the ‘fake news’ from the Bolsonaro camp is coherent and co-ordinated. It forms part of what the historian Virginia Fontes has called a concerted attack ‘in which they [Bolsonaro supporters] call for all those they disagree with and define as enemies to be beaten up, assassinated and to suffer all kinds of humiliation’. Indeed, a scary VICE documentary, broadcast in August, interviewed an administrator of several pro-Bolosonaro WhatsApp groups who said that their material comes directly from Bolsonaro’s head office. More ‘fake news’ is coming fast down the pipeline. According to an investigation carried out by the Folha de S. Paulo newspaper, companies are paying for ‘packages’ of quick-fire anti-Haddad messages to launch on to WhatsApp in the last week of the electoral campaign (21-28 October). A package can cost up to R$12 million (£247,000). The companies are allegedly buying up lists of WhatsApp users from digital companies and the aim is to send out hundreds of millions of messages. Many aspects of this operation are illegal, as under Brazilian law companies are not permitted to fund electoral campaigning nor can candidates buy up lists of voters from third parties. On 19 October PT lawyers took out an action in Brazil’s Electoral Supreme Court (TSE) in an attempt to have Bolsonaro’s candidacy annulled because of the illegal operations that have been carried out. As a result, the level of tension in the country has increased. Patrícia Campos Mello, the journalist who wrote the Folha article, is under constant attack by Bolsonaro fans. Bolsonaro himself hasn’t denied the story but has said that he can’t control what is happening. ‘Voluntary support is something that the PT doesn’t know about and doesn’t accept’, he counter-attacked on Twitter. ‘The PT isn’t being harmed by “fake news” but by the truth.’ He also had a go at the Folha newspaper. ‘It’s really sinking deeper and deeper into the mud’, he said. In its turn, the Folha consulted a lecturer in law, Renato Ribeiro de Almeida, who told them: ‘I can’t imagine a company donating a lot of money without telling the candidate. And, once he knows, he becomes responsible for what is happening.’ The level of abuse used by Bolsonaro’s followers against their opponents, and their willingness to resort to resort to whatever illegal trick they can muster to get their candidate elected, is unprecedented in recent Brazilian history. Virginia Fontes believes that what is happening in Brazil forms part of an international lurch to the right to crush the growing mass of disempowered in the world:But, says Virginia Fontes, she is a historian and she knows that this situation cannot last for ever:Totalitarian solutions with threats to exterminate the left don’t stem from the efficiency or inefficiency of the PT. What is behind this enormous wave of violence sweeping through Congress and Bolsonaro’s campaign is panic in the face of an enormous mass of workers totally deprived of their rights. They are contracted out, flexibilised, turned into nano-businessmen pushed to the outskirts of cities, where they live in a climate of violence. These people will soon demand their rights. It is for this reason that they [the ruling elite] need a Congress capable of annulling existing laws, like Temer has done and Bolsonaro has promised to do more of.

Organised repression against the left, against people of colour, women and homosexuals doesn’t have a future. The assassination of young people in the outskirts of cities can’t sustain governments. All this can appear bloody and terrible, but it will be defeated. The majority of workers are women. Brazilian inequality is a permanent fuse and it is only by confronting the causes of this inequality that it will be possible to get out of the perverse process in which we are trapped.

Main image: Agência Pública/Alan White Fotospublicas