- The Yanomami Park covers 37,000 square miles in the Brazilian Amazon on the Venezuelan border; it is inhabited by 27,000 Yanomami. Soaring gold prices have resulted in a massive ongoing invasion of the indigenous territory by gold miners who are well supported with monetary backing, heavy equipment and aircraft.

- On 3 July, a federal judge issued an emergency ruling ordering the Jair Bolsonaro administration to come up with an immediate plan to stop the spread of the pandemic to Yanomami Park, a plan which must include the removal of all 20,000 invading miners within ten days. Brazil’s Vice President pledges to back the plan.

- That eviction must stay in effect until the danger to the Yanomami of the pandemic passes. There have so far been five Yanomami deaths due to the disease and 168 confirmed cases. More are expected.

- The invasion has also resulted in violent clashes between miners and indigenous people. In mid-June two Yanomami were killed in a conflict, evoking fears of a replay of retaliatory violence that occurred in the 1990s. In response to the current crisis, the Yanomami have launched their “Miners Out, Covid Out” campaign.

On 3 July, the First Regional Federal Court (TRF1), one of the most powerful judicial bodies in Brazil, ruled that the government’s ministries of defense, justice, and environment must draw up within five days a comprehensive emergency plan to stop the spread of COVID-19 into the vast Yanomami Park Indigenous Territory, located in the very north of Brazil, near the frontier with Venezuela, and covering 9.7 million hectares (37,000 square miles).

Federal judge Jirair Aram Meguerian made the ruling in response to an urgent request from the Federal Public Ministry (MPF), a group of independent public litigators, who have become alarmed at reports that COVID-19 is spreading among the 27,000 Yanomami.*

The judge recognized that federal authorities have finally taken some measures to combat the disease, but said those actions were “insufficient” and “ineffective.” He ruled that the Bolsonaro administration’s efforts must go beyond medical treatment and include the eviction of 20,000 invading gold miners, all working illegally in the territory and considered to be the root cause of coronavirus spread there.

Moreover, he decreed that the administration must effectively monitor the reserve’s boundaries once the miners are evicted. The emergency measures, he said, must be implemented within a ten-day period following the announcement of the plan.

The ruling mandates that these emergency measures must be continued until the end of the epidemic — a provision likely aimed at preventing the plan from being easily sidestepped, as has happened in the past, with mine owners removing the miners, and then, as soon as the enforcers have left, sending the miners back in.

While far from providing a permanent solution to escalating conflict in the region, the ruling may give the Yanomami and indigenous health authorities a much-needed breathing space to increase indigenous resilience in meeting the pandemic’s challenges.

The Bolsonaro government could appeal the ruling, but it seems very unlikely. On the day of the judgement, Brazilian Vice President General Hamilton Mourão met with Dário Kopenawa Yanomami, the vice-president of Hutukara, the association that represents the Yanomami and Ye’Kwana indigenous groups, along with federal deputy, Joênia Wapichana, also indigenous.

After hearing indigenous demands, Mourão, who insists there are only 3,500 miners in the territory, nonetheless promised to reinstate the barriers protecting the indigenous territory from invasion and to keep these barriers there permanently. According to the NGO, Instituto Socioambiental (the Socio-Environmental Institute), Mourão told Dário to keep nagging him if there are delays in the implementation of the promised measures. In many ways, this commitment from the powerful vice president is more significant than the judicial ruling, as legal judgements are often ignored in Brazil.

These advances suggest that the Yanomami’s campaign, dubbed ForaGarimpoForaCovid (Miners Out, Covid Out), has brought some success. Waged with the support of national and international organizations, it has relentlessly called on the government to remove the miners who are also doing major environmental harm to the reserve’s forests, rivers and biodiversity.

A clash of cultures brings escalating violence

The number of miners illegally invading Yanomami Park has soared in recent months, driven by several factors: a surge in gold prices on the world market due to global instability caused by the economic meltdown and coronavirus; a high rate of unemployment in Brazil, as the economy enters recession; and a president who has repeatedly said he believes that the Indians have too much land.

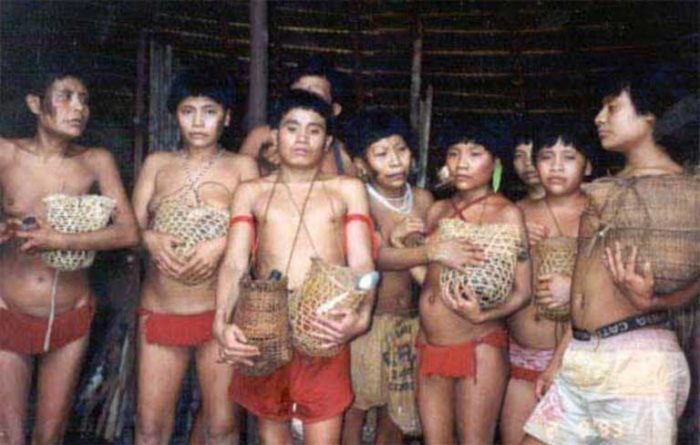

The miners are not only bringing coronavirus to the Yanomami; they are also seriously disrupting indigenous society. Routinely armed and ill-prepared to interact with indigenous cultures with very different codes of behavior, the miners are turning the areas they invade into powder kegs.

One such cultural clash exploded in deadly violence last month. On 12 June, two young Yanomami men were killed in the mountainous Serra de Parima region, a remote corner of the territory near the Venezuelan border. Intense illegal goldmining activity in the area, particularly along the upper reaches of the Uraricoera River and its tributaries, has resulted in heightened tensions. Then a hunting party of five Yanomami unexpectedly came upon two gold miners near an illegal landing strip used to bring in supplies and take out gold.

Startled at the sight of the Yanomami, the miners responded aggressively. “When they saw the Indians, the miners shot at them,” said Júnior Hekuari Yanomami, the president of Condisi-Y, the local indigenous health council, who spoke to the survivors. “One Indian was hit and the others [armed only with bows and arrows] fled into the forest. The miners chased them and killed a second Indian.”

So far, the Yanomami haven’t retaliated. According to Júnior Hekuari Yanomami, they are busy carrying out the involved burial rites required by their culture. After leaving the corpses for 40 days in the place where the conflict occurred, he said, the bodies will then be cremated and the ashes taken back to their home village.

But family members may feel the need to avenge the deaths. In a press release, the Hutukara Association, commented: “We are fearful that, acting according to the justice system of the Yanomami culture, relatives of the assassinated men may decide to retaliate, leading to a cycle of violence.” The association warned that, unless the government acts urgently to evict the miners, there may be another massacre, like the one in Haximu in 1993, also near the frontier with Venezuela.

That clash too came after a surge in global gold prices led to a massive influx of miners and an explosion in violence — the result of what French anthropologist Bruce Albert calls the “gold mining trap,” a recurrent behavioral pattern that facilitates conflict. Outnumbered, the first miners to arrive in an area placate indigenous people they meet with gifts. But, after scores of miners move in, the balance of power shifts and miners stop offering gifts and start behaving belligerently.

In the Haximu conflict, initially friendly miners gained ascendancy then began violently expelling the Yanomami. Four or five were killed. Then the Yanomami, a people with a fierce warrior tradition, made two counterattacks, killing two miners and wounding others. Incensed, the miners launched a retaliatory raid on the village of Haximu, setting fire to huts; around a dozen Yanomami died. Years later, Yanomami elder Davi Kopenawa said: “I will never forget the images. They were my relatives who died. Many children perished.”

COVID-19 makes a volatile situation worse

As in 1993, the miners and Yanomami are again dangerously colliding in the Amazon rainforest, but now with the added provocation of COVID-19.

There have so far been five Yanomami deaths due to the disease and 168 confirmed cases, according to the latest figures from the Rede Pro-Yanomami e Ye’kwana, a network of indigenous organizations, anthropologists and health specialists. To date, only 24% of these cases are among indigenous people living inside the territory, though there are fears that this number is rising rapidly. One report predicts that, in a worst case scenario, most of the 5,400 Yanomami living close to illegal mining could be infected.

Late last week it appeared that the virus was gaining momentum, with reports of suspected cases among the Ye’kwana, a small Indigenous group also living in Yanomami Park. A Ye’kwana from the indigenous community of Waikás visited the settlement of Tatuzão do Mutum, which serves a large open-pit mine, and came back infected. At the same time, some miners with COVID-19 symptoms also appeared in Waikás, seeking medical help. Fiona Watson from Survival International reported a conversation with Nivaldo de Rocha Ye’kwana, who had been in radio contact with the Waikás, where his family lives. Nivaldo said that he had received alarming news: “They [the families in Waikás] say that at least 15 people are ill. Four elders are very weak, with respiratory problems. One of them is my father.”

Ironically, the main vector so far for indigenous coronavirus spread has been CASAI (the Indigenous Health House), a lodging in Boa Vista, the capital of Roraima state, about 150 miles from Yanomami Park, which offers support to indigenous people when they’re sent for treatment to the city’s hospital, the only major medical facility in this Amazon state. No fewer than 80 indigenous people, almost half the total of Yanomami infected, contracted the illness there. There are some, discharged from the hospital after being treated for non-COVID-19 illnesses, who were infected with coronavirus at CASAI while awaiting transport home.

Like babies “left for all to see in a public square”

Cultural dissonance has greatly exacerbated indigenous suffering in this part of the Amazon. Three indigenous women from the Sanema people, an ethnic group related to the Yanomami, were recently taken to a Boa Vista hospital, along with their young babies, all suspected of having pneumonia. None of the women spoke Portuguese. The three babies died, infected with COVID-19. Their corpses disappeared, almost certainly buried in the city’s cemetery — a sound pandemic process, but a violation of indigenous norms. Two of the mothers are still at CASAI, and are imploring authorities to give them the corpses of their tiny children.

Bodies are never buried by the Yanomami, including the Sanema. Corpses are incinerated and ashes kept as part of an extended death ritual that allows the whole community to mourn and move on. “What these mothers are feeling, knowing that their babies are buried in the city’s cemetery, is comparable with what a white woman would feel if the corpse of her child was left for all to see in a public square,” Sílvia Guimarães, lecturer in anthropology at the University of Brasilia, told El País.

Alisson Marugal, the new federal prosecutor in Boa Vista, says she is scandalized by the way the Yanomami have been treated by health authorities. “There have been problems in the treatment, disinformation, and perhaps lack of medical assistance,” she said. “I haven’t ruled out the possibility in the future of prosecuting the authorities for ‘moral damage’ done not only to the parents [of the deceased babies] but to all the Yanomami ethnicity.”

Last Friday’s ruling and the meeting with Mourão bring some glimmer of hope to the Yanomami that the worst outcomes prompted by the mining invasion and pandemic can still be averted. However, analysts say a rapid, decisive and compassionate response will be required, a reaction not evident in the Bolsonaro administration’s past actions. The Yanomami will undoubtedly be continuing their Miners Out, Covid Out campaign for the foreseeable future.

Correction: This story originally put the total number of Yanomami in their reserve at 13,000. The correct number is 27,000.

Banner image: The Yanomami are a proud people with a fierce warrior tradition. Miners, unfamiliar with indigenous customs and culture, sometimes respond with violence, which then can lead to Yanomami retaliation and further escalation. Courtesy Victor Moriyama / ISA.