The author and translator Pritilata Biswas has translated into Bengali the 1990 LAB book: Fight for the Forest – Chico Mendes in his own words.

Pritilata undertook the translation of the book in response to a request from the convener of by the Kolkata-based Gachh Banchao Committee, who are campaigning to save a historic avenue of 4,000 trees that line the busy Jessore Road on the outskirts of Kolkata. The Bengali edition of Fight for the Forest should be published in 2023, by local publisher Mehanati.

In this article Pritilata describes Gachh Banchao’s work and that of other environmental defence campaigns in India. Their experiences closely mirror those of Brazilians in the Amazon and others across Latin America.

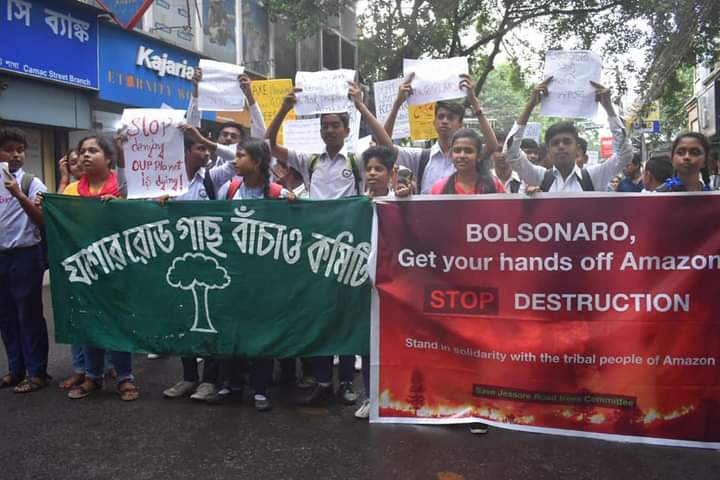

Main Image: members of Gachh Banchao demonstrate outside the Brazilian consulate in Kolkata. Photo: Mehanati

As forest fires raged across the Brazilian Amazon in August 2019, thousands of miles away in India a campaign was gearing up to save an historic avenue of more than 4,000 trees, threatened by a road-widening project near Kolkata.

After news of the Amazon wildfires hit the international headlines, the campaigners in India arranged a rally to the Brazilian Consulate in Kolkata and demonstrated against then Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro for his failure to protect the Amazon.

Local activists, who had set up the Jessore Road Gachh Banchao (Save the tree) Committee, were anxious to find inspiration and precedents in other countries. They came across the name of Chico Mendes, the Brazilian rubber-tapper and Amazon defender, and the book which LAB published in 1990: Fight for the Forest, Chico Mendes in his own words. They were inspired by the book.

Souvik Mukherjee, a frontline activist of the Kolkata-based Gachh Banchao Committee, gave me the Chico Mendes book in February 2022 and asked me to translate it into the Bengali language. When I read it, I realised how important this undertaking was: Candido Grzybowski was quite right when he said ‘The shameful assassination [of Chico Mendes] on 22 December 1988 by the hired guns of the Acre Landowners transformed his words into a political statement.’

While translating the book, I was living in Chennai, a city of southern India, thousands of miles away from Brazil. There I gradually became familiar with the names of places like Japuri, Acre, Parana, Brasilia, Rio Branco, etc. Subsequently, I wrote a letter to the LAB to ask their permission to publish the translated version. They were happy to agree, and asked me in turn to write this article about our campaign in India. We are hoping that our local publisher, Mehanati (which means ‘working people’) will be able to launch the Bengali version of Fight for the Forest soon.

Save the Jessore Road trees

The Gachh Banchao Committee are trying to save the trees which form an avenue on both sides of Jessore Road in North 24 Parganas (near Kolkata city) in the east of India, on the route to Petrapole on the border with Bangladesh. These century-old trees are threatened by a road-widening project.

In 2015, a local human rights organisation was the first to object to the tree-felling project and to organise protests. In 2017, a group of students and local people formed a committee called ‘Jessore Road Gachh Banchao (Save the tree) Committee’. Gachh Banchao challenged the official order which was based on a no longer valid Tree Act of 2006. The Kolkata High Court issued an injunction to halt the felling.

The committee campaigned among common people by collecting signatures, putting up posters, organising meetings and street theatre, staging bicycle rallies, and walking rallies over a 56km distance. They held public hearings, and spent their days and nights camped under the trees in order to explain to people their importance.

Whenever the local authorities sent lumberjacks to fell the trees, young people embraced and encircled the trees forming human chains. They were following the strategy used by women in the Chipco Movement in Uttarakhand to save trees in 1970, which eventually developed into a powerful national ecology movement. The committee argued in court that the trees should be declared as part of the city’s heritage.

Eventually, in 2019, the High Court gave its verdict. It sanctioned the felling of just 356 trees instead of the more than 4,000 trees identified for ROBs (railway over bridge). The committee challenged this verdict and appealed to the Supreme Court. Unfortunately, on 8 February 2023, the Supreme Court upheld the verdict of The High Court.

India’s history of environmental defence

India has a century-long history of fight against deforestation and environmental destruction, stretching back to the colonial period. It is striking how closely the Indian experience mirrors that of environmental defenders in Latin America. Here are some of their most important battles:

Bastar

Bastar is a region in southern Chhattisgarh, a state of India that is densely forested and inhabited by at least four different tribes. The river Indravati, flowing across the region, makes the land cultivable. The livelihoods and traditions of the tribal peoples in this region are inextricably intertwined with the forest. These tribal lives remained unchanged for over a millennium.

However, during the colonial period, the Indian Forest Act of 1878 was passed and had a direct impact on tribal lives. The richest part of the forest was declared as the ‘reserved forest’ and was to be directly controlled by the government 1)LAB has documented similar experiences with ‘reserves’ in Peru, Brazil and Belize. Two-thirds of the forest was snatched from its dwellers and overnight, they became ‘trespassers’ in the very forest in which they had been living for centuries in symbiotic harmony.

Additionally, high tax rates, forced labour and a ban on brewing liquor stifled their means of livelihood, pushing these tribal peoples into starvation. As a result, in 1907–8, a terrible famine broke out in Bastar. The irony of the situation was such that while the tribals were not allowed to enter the jungle for hunting, contractors were given access to the reserved forest to collect timber and wood for railway sleepers.

Naturally, following these events, the tribal communities became rebellious and under the leadership of the iconic Gundadhar, the ‘Bhumkal Revolution’ broke out in February 1910. Although, the police managed to crush the revolution swiftly, the area of the forest designated as reserve was reduced. Gundadhar’s memory is still honoured in the area and his legacy has been carried forward by generations of tribal people in Bastar.

After independence

Following India’s independence in 1947, the tribal peoples did not get back their former freedom and life in the forest. In the late 60’s, a peasant uprising in Naxalbari, a small village at the foothill of Himalayas in the state of West Bengal, led to an armed struggle against State Power. Although the uprising was suppressed, the fire ignited by Naxalbari would go on to spread across large parts of India and burns till today.

The followers of this Maoist communist political philosophy are commonly known as Naxals or Naxalites. For decades, Bastar has witnessed increasing deployment of armed forces into their dense forests and hilly region, as part of the state’s war against the Naxals.

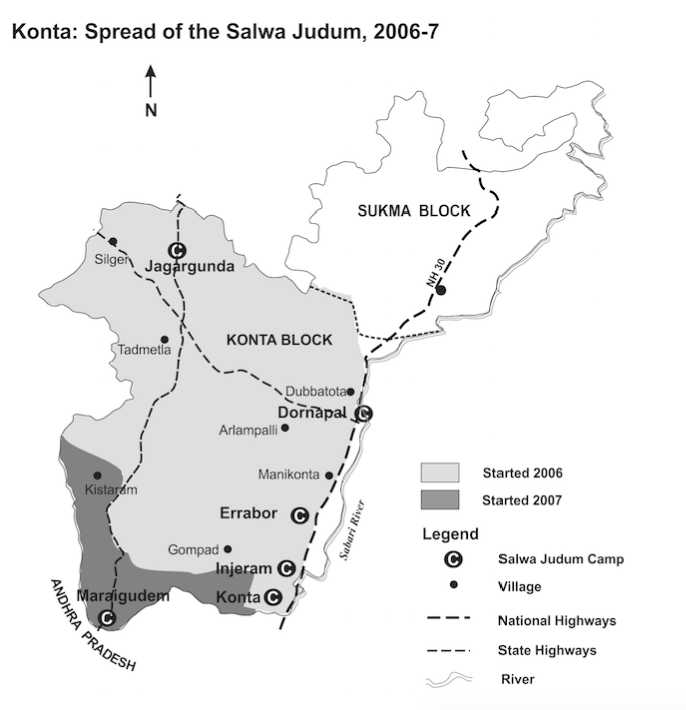

In 2005, the government formed Salwa Judum, a militia that comprised thousands of untrained tribal people, as a part of their counterinsurgency operation 2)This government policy echoes that pursued by the Rios Montt government in Guatemala in the 1980s, with its use of civilian militias and ‘strategic hamlets’.. State-sponsored terrorism spread across Bastar. The Supreme Court outlawed and banned Salwa Judum in 2011 because of the rise in human rights violations, but it continues to exist in the form of armed auxiliaries.

There is an ongoing confrontation in Silger village in Bastar following the secret establishment of a camp by the security forces, in the early hours of one morning in May 2021. Such security camps, set up under the pretext of protecting highways, exist in some areas at intervals of about 5 km.

Yet their presence sparks conflict and resentment. First, the construction of these camps, involves cutting down swathes of forest and excavating unstable hillsides for roads, which wreaks havoc on the environment. Secondly, the villagers are afraid of harassment by the army personnel. The ratio of police to civilians in some short stretches in Bastar is among the highest in the country. Beating villagers up, detaining them for trifles and confrontations have become routine occurrences in these villages.

The result is a deep-rooted fear among the young people of this region. Perhaps to counter this fear, the youth of Silger, aged 17–22 have formed the ‘Moolwasi Bachao Mancho’ (Platform to Save Indigenous People) and have started a sit-in against the setting up of police camps and destructive road construction. These protests are still in progress.

Narmada Bachao Andolan

In the Indian peninsula, the river Narmada is the largest west-flowing river with around 41 tributaries, surrounded by 3 mountain ranges and eventually flowing into the Arabian Sea. Soon after independence, the Indian Government proposed the Narmada Valley Development Project which included 30 large, 130 medium and 3,000 small dams along the course of the river. 3)LAB’s book Voices of Latin America (2019) has a chapter on The Hydroelectric Threat to the Amazon Basin.

The project was approved by the Narmada Water Disputes Tribunal and inaugurated with minimal information provided to the more than 250,000 people who were to be displaced from the valley. Most of these uprooted people belong to different Indian tribes whose primary occupation is agriculture.

Medha Patkar, a renowned environmental activist united these people and started the Narmada Bachao Andolan (Save Narmada Movement) in 1985. Narmada Bachao Andolan progressed through sit-ins, hunger strikes and rallies to spread awareness. The purpose of this movement was to push for the resettlement of refugees.

In consequence, in 1994 the World Bank and other international funders stopped their contribution to this project. Although the project was completed in 2006 and inaugurated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2017, the Narmada Bachao Andolon was a powerful mass movement that succeeded in drawing nationwide attention and inspired people to fight against environmentally unsustainable, anti-people development projects.

Deucha Pachami Coalfield

Spread over an area of 12.31 sq km. in the state of West Bengal, Deucha Pachami is said to be the world’s second largest greenfield coalfield. In 2018 the Coal Ministry of India entered into an agreement with the West Bengal Power Development Corporation Limited to allocate mining concessions. The West Bengal government put forward this opencast coal mining project just at the moment when India proposed phasing down coal in COP26. 4)LAB has reported extensively on the impacts of the El Cerrejón open-cast coal mine in Colombia.

For this project 21,000 Adivasis (indigenous people) are on the verge of losing their land and may be relegated to the category of migrants. The compensation package includes money and 600 sq.ft of living area. Most of the inhabitants refused to vacate their land and accept the compensation package. Activists also raised the questions of environmental clearence which is yet to be assessed. Resistance is continuing.

The Himalayan range in the North, the Decan Plateau in the central India, and the three seas on its three sides are responsible for India’s tropical climate. Human beings started inhabiting this land 65–70,000 years ago. Ethnic diversity and biodiversity are integral parts of India. However, the growing corporatization of public sectors, together with capital-generating development projects are causing the decline of these diversities. Projects such as the ones I have described enable the wholesale looting our natural wealth while they deny the rights of indigenous people who live in symbiotic harmony with nature.

That is why we in India, like hundreds of thousand of Brazilians, are deeply touched by the messages of Fight for the Forest.

References

| ↑1 | LAB has documented similar experiences with ‘reserves’ in Peru, Brazil and Belize. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | This government policy echoes that pursued by the Rios Montt government in Guatemala in the 1980s, with its use of civilian militias and ‘strategic hamlets’. |

| ↑3 | LAB’s book Voices of Latin America (2019) has a chapter on The Hydroelectric Threat to the Amazon Basin. |

| ↑4 | LAB has reported extensively on the impacts of the El Cerrejón open-cast coal mine in Colombia. |