This article was published by the author on his blog on 30 November.

As irresponsible, dangerous and frankly disgraceful legislative proposals go, at least in the human rights and environmental spheres, this one must be right up there with the best of them. Midway through this month an otherwise obscure Peruvian congressman, Jorge Morante Figari, proposed a bill that arguably constitutes the most serious threat seen in decades to the lives, lands and survival of indigenous peoples who live so remotely in Peru’s Amazon that they have no regular contact with anyone else.

The bill, formally supported by five other members of Morante Figari’s party, Fuerza Popular, seeks to modify a 2006 law on indigenous peoples in “isolation” and “initial contact”, as such groups are commonly known in Peru, other countries and by the United Nations. This includes transferring the powers to establish reserves for the “isolated” peoples – as well as eliminate existing ones – from the Ministry of Culture and President in Lima to regional governments in the Amazon. It also includes putting the regional governments in charge of the MultiSector Commission responsible for the administrative process required to establish reserves, as well as reducing the Commission’s size and booting off the Environment Ministry, the National Ombudsman and Peru’s two Lima-based federations representing indigenous peoples in the Amazon.

One of those federations, the Asociación Interétnica de Desarrollo de la Selva Peruana (AIDESEP), said in a furious public statement that passing the bill “would cause genocide.” Alleging that “direct economic interests” are behind it, they are urging legislators to reject it outright and instead respect the “national and international legal framework protecting the rights of our brothers and sisters in isolation” which the “Peruvian State has an international obligation to comply with.”

While decentralising governance might sound positive in the abstract, the fact is that regional governments in Peru have consistently failed to contribute to respecting the rights and territories of indigenous people in “isolation”, or actively violated those rights themselves. If these proposed changes were to come into law, it is safe to say there would be no more new reserves, ever, despite the fact that four proposals remain pending, and all seven existing reserves could be eliminated. This would potentially open up millions of hectares of the remotest Amazon to logging, mining, oil and gas operations, colonisation, coca cultivation and road networks, among other things, and possibly have devastating consequences for the people living there.

As indigenous federation ORPIO, based in the Loreto region, put it in its own scathing response to the bill, “it is precisely those authorities and representatives [the regional governments] who have repeatedly denied the existence [of the “isolated” peoples] and who are permanently putting their lives at risk.” ORPIO said passing the bill would be a “crime against humanity” and that it “prioritized the exploitation of natural resources over the human rights of the peoples in isolation and initial contact, and the environmental impacts on the forests and rivers of the Amazon.”

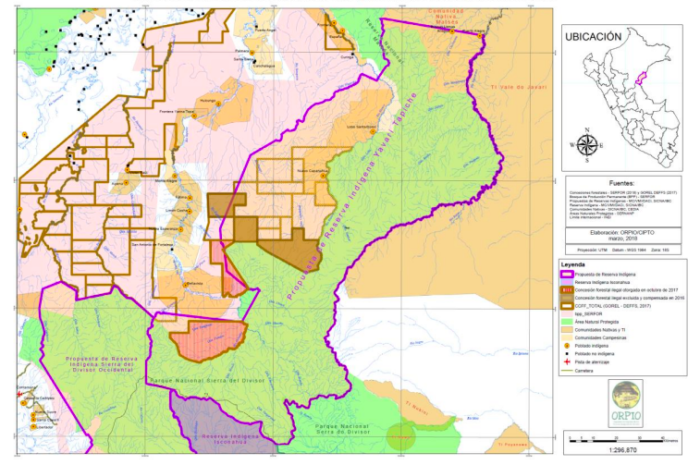

The timing is eminently conspicuous. The first five reserves for “isolated” peoples in Peru were established between 1990 and 2002, but then it took almost another 20 years for the next two to be created, both in 2021. One of those, the Yavari Tapiche Reserve in Loreto, which Morante Figari represents in Congress, has been particularly contentious because it is overlapped by logging concessions established by the regional government (GOREL), leading ORPIO, supported by the NGO Instituto de Defensa Legal, to take legal action in an attempt to force GOREL to relocate or abolish them. Just one week before Morante Figari submitted his bill, Loreto’s Superior Court of Justice ruled, in an historic sentence, that GOREL must not “grant” or “reactivate” any logging concessions including any part of the Yavari Tapiche Reserve or three other proposed reserves in Loreto.

To what extent is this bill, more than anything, a crude attempt by a largely Loreto-minded cabal – best illustrated by the involvement of the so-called Coordinadora por el Desarrollo de Loreto, which has been promoting it – to extinguish the new Yavari Tapiche Reserve? Either that, or block the establishment of the proposed Yavari Mirim Reserve, which would be overlapped by even more logging concessions, and/or the proposed Napo Tigre Reserve, which moved one crucial administrative step closer to creation in September? It is eminently conspicuous too that of the 22 pages of the “explanatory memorandum” accompanying the bill seven of them are devoted solely to Napo-Tigre. Included among all that blahblahblah is the intriguing admission that an indigenous federation called FECONACA, which claims to represent five indigenous communities in the Napo-Tigre region and has filed a lawsuit effectively trying to block the reserve, lobbied Morante Figari about this issue last year.

Not unsurprisingly, that “explanatory memorandum” fails to make clear that right across what AIDESEP and ORPIO have hoped for years would be the Napo-Tigre Reserve are two oil concessions, both run by UK-France-based company Perenco, which was also trying to block the reserve’s establishment by taking legal action until it desisted earlier this month. The five communities that FECONACA apparently represents – four of which I’ve visited – are the very same five that Perenco told me that it works with “closely” and supports “across many areas including infrastructure projects, transport, health and employment.” In other words, those communities don’t only stand to benefit from the Napo Tigre Reserve never being established because it would or should limit their access to forest beyond their territories where they could fish, hunt game or log timber, but because they’re living off the oil too.

Has Morante Figari, who was elected to Congress after winning less than 6,000 votes, ever had any kind of contact with Perenco? That is a question obviously worth asking, but to date he has not replied.

Update: Approximately six hours after this article was published, Morante Figari replied saying: “I haven’t had any type of contact with anyone from the company Perenco.”