Focussing on institutional violence in the case of the Guatemalan Hogar Seguro tragedy in a State-run children’s institution, as well as other cases of militarized violence, this digital chapter shows how women’s resistance is essential but also difficult and often dangerous. Nevertheless, up against the power of the state, it is often ordinary women who rally together, collectively seeking to honour victims, support their families, and to demand justice. This chapter focuses on women’s creative acts of memorialization and commemoration, demonstrating how acts of mourning become sites of mobilization, active resistance, and empowerment. It highlights the power of the arts in denouncing and resisting state violence and impunity.

This is the final chapter of LAB’s recently-published Women Resisting Violence: Voices and Experiences from Latin America, by the WRV Collective. The book is part of a wider collaborative project between LAB and King’s College London, which comprises the book, a podcast, and events, and was funded by the ESRC Impact Acceleration Account held at KCL and the National Lottery Community Fund. You can purchase the book, in physical or digital form, here. This chapter was written by Jelke Boesten (KCL) and Louise Morris (LAB).

Voz brings our loyal subscribers a long-read article each quarter, conveying the experience and analysis of our partners: activists, journalists, artists and academics. We hope that their in-depth testimony and commentary will help broaden our understanding of Latin America, and through it, the world.

In a sprawling cemetery on the outskirts of Guatemala City, Vianney Hernández, a petite woman with a careworn face weaves her way determinedly to a grave. It has taken her hours to get there, paying for bus fares she can seldom afford. She kneels and makes a promise to her daughter, Ashly Angelie Rodriguez Hernández, buried there aged just 14: ‘You… you… my girl, you know me well and I won’t ever stop demanding justice for you’.

In the early hours of 8 March 2017, Ashly was burned alive, together with 40 other girls at the so-called ‘Hogar Seguro’ (Safe Home) Virgen de la Asunción just outside of Guatemala City. 15 more girls survived but with physical and psychological scars they will carry with them for life. The 56 girls aged between 14–17 were imprisoned by police officers in a classroom of 23 by 23 feet, with no food or sanitation, after they attempted to run away from Hogar Seguro when long-standing complaints of abuse and sexual trafficking had been ignored. A fire was started and dramatically escalated, with the girls screaming to be let out. The police officers guarding the classroom ran to alert their boss, Lucinda Maroquín, who had the key, and they reported that she said: ‘Let them burn, let them burn, those dirty little bitches’. It took nine minutes for them to unlock the door. Vianney Hernández tells of the horrors of the events and the aftermath, and the families’ struggles to see justice for their children, in the Women Resisting Violence podcast (Episode One: Mourning the 56 in Guatemala).

It seems sinisterly ironic that this massacre at a state-run children’s institution took place on 8 March – International Women’s Day – a sharp reminder of the brutal disregard of female life in Guatemala. While it is difficult to know the exact numbers, Guatemala is amongst the countries with the highest rates of femicide in the world, alongside El Salvador, Honduras, and Bolivia. In 2021, 531 women were murdered in Guatemala according to the Women’s Observatory; that is 44 per month. Faced with such high rates of violence against women, and such limited state intervention, it is women’s groups that mobilize to resist and protest the violence they are subjected to every day.

In cases of militarized violence, for example during conflict, or institutional violence as in the case of the Guatemalan Hogar Seguro, women’s resistance is not only essential, but also difficult and often dangerous. Nevertheless, up against the power of the state, it is often ordinary women who rally together, collectively seeking to honour victims, to support their families, and to demand justice through the courts, protests, and memorials. The latter public-facing demands for justice are often presented creatively: women have used symbols – like the white headscarves worn by the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo in Argentina protesting their disappeared children, or the green kerchiefs worn at pro-abortion protests throughout Latin America. They have used performance art – as in the ‘Red Carpet’ protests in Peru, in which women dress in red and lie on the streets to form a carpet in protest against impunity for the violation of reproductive rights. And women have staged memorials – like the pink crosses placed in front of Court buildings to protest against femicide and impunity in Mexico, or the murals painted on Honduran and Mexican city walls to commemorate victims of femicide.

Commemorative practices are essential in shaping political cultures of inclusion and in resisting impunity. Acts of violence themselves are often commemorated and publicly repudiated, providing political and social commentary on what is acceptable and what not. Acts of violence that are not remembered, are ignored, or forgotten, or even deliberately obscured and erased by complicit powers, send a message to society that gendered acts of violence are not relevant. The victims of such violence are thus not considered relevant either, not in need of protection, or justice, or prevention. Political elites benefit from the invisibility of the victims of these multiple forms of violence and silencing them perpetuates the persistence of violence and marginalization. But women consciously and unconsciously resist such erasure, which we will discuss below. This chapter will focus on women’s creative acts of memorialization and commemoration and how these acts of mourning become sites of mobilization, active resistance, and empowerment (see also Boesten & Scanlon, 2021).

Political violence and gendered memory

Remembering gives us tools to analyse the present and hold history to account. For example, public acts of remembrance can help us to identify historical colonial structures in our present time and mobilize us to contribute to a more equitable, decolonial future (Lugones, 2010). Looking back on atrocities committed against particular groups of people such as women, Indigenous people, or LGBTQ+ people also allows us to frame such violence as violence, instead of as collateral damage or incidental occurrences. This was consolidated, for example, by women who actively and publicly protested against political violence in the 1970s, in particular in the Southern Cone.

The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo in Argentina understood very well that their children were not only being killed by the state, but deliberately being erased from memory. They understood that this erasure gave the military dictatorship (1976-83) the possibility to continue its murderous practices. Drawing some protection from their status as mothers in a highly patriarchal society, the women of Plaza de Mayo staged the most forceful and visible protest possible during and after the years of repression, stoically circling the Plaza every Thursday armed with white headscarves and photos of their disappeared loved ones. Their protests have not been in vain: children taken from prisoners have been identified and matched up with their abuelas, laws have been passed, and some justice has been achieved.

Peruvian mothers did something similar in the 1980s, when their children and husbands started to disappear due to the conflict between the violent insurgent group Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) and the Armed Forces. They first organized clandestine networks to share information and support each other’s families. Then, like the Argentine mothers, they began to march with images of their loved ones, asking for justice. During the transition to democracy, after the year 2000, they stepped up their commemorative activities and became vocal activists for post-conflict justice, with demands for investigations and exhumations, and the clear marking and memorialization of burial sites.

Marking the sites of the mass atrocities perpetrated by the Peruvian military is still a politically contentious issue: investigations carried out since the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was established in 2001 have recovered the remains of hundreds of people at fields behind a military base in highland Ayacucho, as well as the foundations of an oven that served to burn human remains in the 1980s. Since 2007, veterans have invaded this land to build houses, denying any relevance to what occurred in the space, or to those suffering loss after the tragic events. The mothers’ organization, known as ANFASEP (Asociación Nacional de Familiares de Secuestrados Detenidos y Desaparecidos del Perú – National Association of Family Members of the Kidnapped and Disappeared in Peru), continues the fight to turn the field, La Hoyada, into a memorial site to mourn and commemorate their loved ones. Such mourning is highly political, as it not only involves commemorating the dead, but also highlighting state atrocity and impunity.

The mothers of the Plaza de Mayo and the Peruvian mothers of the disappeared of ANFASEP are responding to state violence committed during military dictatorships and political conflict. Their memorial activism is related to and can be analysed as part of what we call transitional justice – the political process that marks the transition from state violence to democracy (Boesten, 2021). Transitional justice processes generally include memorial activities, from truth-seeking processes to memory museums. Nevertheless, as recently published research in multiple transitional countries has pointed out (Boesten & Scanlon, 2021), women’s representations in such memory works is often limited and grounded in stereotypes of victimhood. Beth Goldblatt and Sheila Meintjes pointed out in 1997 that the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) did not ask women about their experiences; they were expected to speak about the fate of their husbands and children. Women’s own roles and contributions to the struggle, or their victimization, were downplayed or even silenced. Their roles were defined through their relationships with men and children. Of course, such conclusions help explain why the mothers of the disappeared in Argentina and Peru were considered relatively ‘safe’ as political actors developing motherhood and caring activities: so long as women define themselves in relation to men and children, they are not considered political actors in their own right. The activism of these mothers and wives is anything but innocent, of course. They know that their demands are political and that their memorial acts contribute to resistance and justice.

The exclusion of women’s voices in much official commemorative work – TRCs, memory museums, naming practices of public spaces to commemorate heroes of war – pushes women into activism in order to have their say. If we want to see what women’s roles were during particular episodes of political violence, then we should look towards the arts. Poetry, music, and visual and performance art can often be more radical, accurate, and transformative in its depiction of women’s experiences than ‘official’ commemorations. Similarly, women’s experiences of non-political gender violence are often ignored and therefore politically denied. Creative activism is a powerful response, demanding accountability for violence, commemorating those who have lost their lives in these instances, and reminding society – its judges, lawyers, and police officers, politicians, policymakers, and journalists, as well as ordinary men and women – of the violent and unnecessary deaths of women and girls.

The Sepur Zarco case: sexual slavery on trial

In 2016, a groundbreaking trial took place in Guatemala, the first of its kind in Latin America. After two weeks in Guatemala’s High Risk Court – which was set up especially to deal with high-profile cases requiring extra security measures due to the levels of violence and intimidation that persist within the state – two ex-military officers were convicted of sexual and domestic slavery.

The case is known as Sepur Zarco, after the community where the atrocious events took place in the 1980s during the Internal Armed Conflict. During the war, government forces targeted Indigenous communities with extreme genocidal violence, for which the then president, Rios Montt, was convicted in 2013, by the same brave High Risk Court. The verdict was overturned by the Constitutional Court soon after. Nevertheless, the Rios Montt trial created an important precedent for the possibility of justice for crimes against humanity and it generated confidence in the system. In addition, the ruling included the consideration of sexual violence against women as a tool of genocide and took women’s cultural position as reproducers of community into account. The case laid the groundwork for the 2016 Sepur Zarco case.

While the case was successful in terms of conviction and procedure (see Burt 2019, Boesten 2022), the surviving women are still fighting for reparations. A dignified rollout of reparations requires a competent and willing government, which is problematic in many cases. However, with the help of national and international NGOs, these women work to keep the memory of what happened at Sepur Zarco alive – through testimonials and even plans for a comic book for children. These are difficult stories to tell, but commemorating the atrocities in a sensitive way could be transformative not only for the women and their families, but for Guatemala as a society, and indeed, for gender justice.

El Hogar Seguro, Guatemala

A group of feminist activist friends who were following the situation at the Hogar Seguro children’s home in Guatemala on local television – from the girls’ escape from the home to their detention and the fatal fire – decided to get together, determined not to let this be another forgotten tragedy in Guatemala’s history. The group went straight to the morgue to support the affected families, and then organized themselves in a support group called Ocho Tijax (named after the tragedy’s corresponding date on the Mayan calendar, with tijax – obsidian – representing a cut or a blade, or overwhelming division, pain, and separation).

The girls were in the Hogar Seguro because of difficult situations at home or because they had run away or were vulnerable to trafficking; they were not criminals, but they were teenagers from poor socio-economic backgrounds and vulnerable in a violent and misogynist society. They were at this state institution supposedly for their own protection, but were met with further abuse, and even trafficking, according to the girls’ claims. When they attempted to escape their situation, they were caught and eventually left to burn alive. A smear campaign accusing the girls and their families of criminal behaviour served to undermine any calls for justice coming from the children’s families. Yet the solidarity of Ocho Tijax, a group of professional women Mayra Jimenez, Quimy de León, Maria Peña, and Stef Arreaga, has allowed for a sustained campaign to keep the memory of the girls alive, and to pressure the state and the judiciary to take responsibility and seek justice.

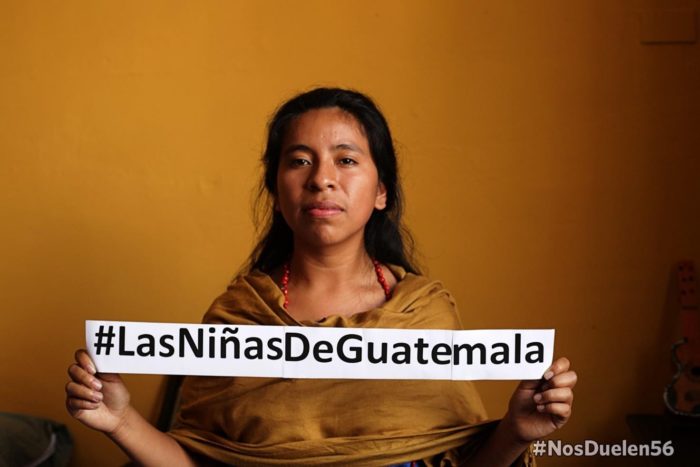

Today, Ocho Tijax continues to accompany the families and the few survivors through medical and legal processes: they organize juridical counselling; physical and emotional healing therapy and psychology sessions for the survivors; and financial aid to cover transportation and other costs related to their campaigns for justice. In addition, and most visibly, they work to keep the children’s memory alive. Ocho Tijax are affiliated with the media campaign NosDuelen56, which is organized by the families of the victims and focuses on demanding justice through the arts and journalism. The campaign exists to preserve and dignify the memory of the 56 teenage victims through collaborative cultural projects. Soon after the fire, NosDuelen56 built a memorial in Guatemala City’s central square, Plaza de la Constitución, where relatives of the deceased gathered every Friday to honour the girls’ memory and demand justice. In September 2019, the police removed the memorial, but it has since been replaced. Centrally located for everyone to see, the campaign is a powerful reminder of the state’s responsibility and its neglect.

Another project NosDuelen56 carried out was a call to artists from all over the world to create portraits of the girls who died in the fire. In the campaign, 58 artists from Mexico, Italy, France, Spain, Argentina, and Guatemala participated and publicized the open call in their own countries. A follow-up call was made to invite more artists to join in creating images to support the campaign #NosDuelen56. One of the Guatemalan artists who participated was Sara Curruchich, an Indigenous Kaqchikel artist, composer, and singer who stressed the importance of the quest for justice:

‘It’s important to shine a light on the ways in which history and justice in Guatemala have been covered up, like the history of people suffering. This is happening yet again with the femicide of young girls. From our spaces [as artists] we demand justice, and we want to speak out for the girls – the survivors and those who died – who have left us with their strength to continue fighting for them.’ (Rivera, 2017)

All this pressure has led to a judicial process against the director of the home and several other officials, but the process is littered with obstructions and delays and hearings have been continually postponed. Surviving relatives have faced mistreatment in court and those involved in the campaign, including the girls’ families and their lawyers, have been intimidated and threatened. The Ocho Tijax collective itself has been intimidated, followed, and violently threatened, and is still receiving death threats today. Since the massacre in 2017, three relatives of the victims have been murdered – Gloria Pérez y Pérez, mother of Iris Yodenis León Pérez was killed in July 2018, alongside her 13-year-old daughter Nury León Pérez; María Elizabeth Ramírez, mother of Wendy Vividor Ramírez, was killed in February 2021. Recently, Elsa Sequín, another mother who works with Ocho Tijax and NosDuelen56, received death threats. Some activists involved with the campaign have fled the country for fear of retribution. As these activists emphasize in the podcast, considering the violence of the Guatemalan state and its disregard for and participation in violence against women and girls, keeping the memory alive through creative campaigns both inside and outside of Guatemala is extremely important.

Art, memory, and mobilization

Contemporary feminist art often places memory at its centre, as the podcast on Guatemala’s Hogar Seguro case so clearly indicates. Remembering in the arts is more than recording events or experiences for posterity. Particularly in feminist art, memory often works as a reflection on the present – as a questioning, or perhaps a mirror of ongoing injustices. Artists such as Doris Salcedo (Bogotá, 1958), Natalia Iguiñiz (Lima, 1973), Lucila Quieto (Buenos Aires, 1977), and Claudia Martinez Garay (Ayacucho, 1983), draw on personal and collective memory to reflect on trauma, loss, and its aftershocks. In doing so, they also denounce the violence that caused the harm, allying their art to feminist activism. Apart from her more static photographic representations of the physical ruins of violence, Natalia Iguiñiz has also created arts-based research about a particular feminist activist brutally killed by political violence in 1992. In examining the life and work of María Elena Moyano, who was murdered and dynamited by Shining Path at a community event, Iguiñiz reflects on how Moyano was treated by political allies and enemies and offers a mirror to contemporary activists and politicians alike. Moyano’s multiple identities as a feminist and political organizer and the intersecting factors of inequality that affected her as a Black woman of poor background made her life vulnerable as well as exemplary for so many others. Indeed, in response to the question around what memorial art is, Amanda Jara, daughter of Chilean protest singer Víctor Jara says, ‘It’s looking at ourselves, and seeing where we’ve come from, what we’ve done – it’s looking in the mirror’ (Morris, 2017).

The life and work of María Elena Moyano

María Elena Moyano was an Afro-Peruvian working-class woman, a political organizer in the United Left and a leader of women’s organizations in her district. In the last years of her life, she was elected Deputy Mayor of Villa El Salvador, a self-built neighbourhood in the southern desert of Lima. Moyano mobilized the women in Villa to resist the violence of the State, Shining Path, and of their own husbands and boyfriends. She set up community kitchens to feed those in need and share the burden of care, she lobbied the local government for foodstuff and support, and she established alliances with middle-class feminists. She was also a clear target, and in her last visit to Villa while planning her escape to Spain, she was shot and dynamited in front of the community and in the presence of her children. The immediate political effect of her murder was a certain spread of fear and a weakening of the women’s movement throughout the country, but she soon became a martyr of resistance. However, when the leadership of Shining Path was captured in the same year, 1992, Moyano’s memory was co-opted.

As Jo-Marie Burt has argued (2011), Moyano’s progressive and feminist politics were erased by opportunist political actors keen to capitalize on her widespread popular appeal. According to Burt, Moyano’s memory was invoked in a Fujimorista discourse against Shining Path, as if she had supported the government and political movement led by dictator Alberto Fujimori 1990-2000. But Moyano had resisted the harassment and manipulation of the Fujimori government, recognized its abuses of human rights, and openly fought against its social and economic policies directed at her sector of society.

Besides the erasure of her left-wing politics and resistance to the Fujimori regime of the 1990s, through this co-optation, her feminism has hardly been remembered. The community care work of Maria Elena Moyano and her colleagues in women’s organizations in Lima and throughout the country was political, as demonstrated through the responses of Shining Path – attempts at infiltration, defamation, threats, and even killings. Their work was also radical in its feminism: through their collective efforts, the women created vast networks of solidarity and learning that allowed women to defy patriarchal adversaries at home as well as on the streets. One of María Elena’s colleagues who in 2018, when we spoke with her, still worked at the Casa de la Mujer – which they collectively set up in the 1990s – told us that it was María Elena who taught them about women’s rights, and that learning about politics, including what we would now call gender politics or feminist politics, was very much part of their everyday engagement with the women’s movement that María Elena had started in Villa El Salvador. Likewise, a young woman we met there, Carola, who works to encourage other young women in Villa to ‘think politically’, looked up to the memory of María Elena Moyano as her inspiration. So, when attending contemporary meetings at the Casa de la Mujer in Villa El Salvador, the community space originally established under María Elena’s leadership, it is clear that her memory as a women’s rights organizer is very much alive, and directly feeds into the contemporary struggles for women’s rights and autonomy.

Natalia Iguiñiz, a visual artist based in Lima, studied her mother’s archive for traces of María Elena. Iguiñiz’s mother was a leftist activist in the 1980s and 1990s and had been friends with María Elena. Tracing this friendship through conversations, photographs, and letters, Iguiñiz made a series of portraits of Moyano that highlighted her feminism, her activism, her anger at injustice, and her joy in collective action. She then pasted a series of these portraits as posters on walls and columns in public spaces where contemporary Fujimoristas, including Moyano’s own sister, had co-opted Moyano’s memory for their own benefits. The resulting artwork, ‘Buscando a María Elena’ (Looking for María Elena, 2011), records a different memory of Moyano’s life and her work; a memory that corresponds with the memory her friends have of her, and that captures what inspires contemporary and future generations.

The crossover between art and activism is often referred to as artivism. Those artists who explicitly use their art for political purposes, as in the case of much of Iguiñiz’s work, are often themselves active in broader social mobilizations as well. For those themes and issues that are not considered on mainstream political agendas – such as women’s rights and particular forms of political violence including the harassment of human rights defenders throughout the continent – creative forms of activism are a must. Arts including theatre, visual art, music, poetry, and dance tend to reach much wider and differentiated audiences than a street march can. Art is also a particularly powerful outlet for expressing historical trauma which is otherwise difficult to encompass, particularly those traumas that tend to be erased from formal commemorative practices. Thus, in the case of feminist activism in Latin America, the collective trauma of the infringement of basic human rights and continuous violence against women and the LGBTQ+ community in homes, public spaces, and in institutions, is increasingly mobilized in powerful manifestations of art and activism.

Regina José Galindo

Born in 1974, Regina José Galindo is a performance artist and poet from Guatemala City. Regina harnesses art’s emotive power to question histories of state violence and impunity and speak out on behalf of those affected. Her work often symbolically places her body in direct opposition to power, and under physical duress.

In one of her most famous performances Quién puede borrar las huellas? (Who Can Wipe Away the Footprints, 2003) she walked a bloody path from the Constitutional Court to the National Palace in Guatemala City, dipping her feet in human blood in memory of the Guatemalan armed conflict’s victims and in rejection of the new presidential candidacy of General Efraín Ríos Montt who presided over some of the bloodiest years of the conflict. The performance won her the Golden Lion for Best Young Artist in the 51st Biennale of Venice (2005).

Regina states that her work is ‘related to my context and my context is inevitably what happened with my history – so it’s inevitable that all of my work has to do with death, impunity.’ It formidably interrogates the pervasive trauma of Guatemala’s national memory, creating combative and powerful symbols of resistance.

Speaking out in the face of extreme opposition is also the main theme in performance artist Regina José Galindo’s piece La Verdad (The Truth). She sits centre stage reading aloud testimonies of the Indigenous Maya people who suffered massacre, torture, and rape at the hands of the Guatemalan military during the war. Many of them are witness statements by Maya Ixil women and have been taken from the April 2013 trial on genocide charges of Guatemala’s former president, General Efraín Ríos Montt. Every 10 minutes, a dentist comes and injects Regina with anaesthetic, attempting to obstruct her speech. Over the course of the 60-minute performance, Regina’s speech becomes increasingly muffled, but her words never cease.

Her work packs a visceral punch, embodying the difficulty and determination of speaking out in the face of injustice as well as becoming an homage to the memories of those affected, by repeating their stories. Actual testimony is central to the power of the piece, and Regina creates a striking physical metaphor of the Guatemalan state’s attempt to silence victims of the war.

‘My body was holding on with the purpose of demonstrating what I had learned about the strength of these women – because these women in the justice process of Rios Montt never faltered and the process was very long and torturous. In the end it was cancelled. The whole process was very conflicted, with every type of prevention, but these women continued with all of the force of the world.’

Regina’s work has long focused on endemic violence in Guatemalan society, and in particular violence against women. Shortly after the murder of the 41 girls in the Hogar Virgen de la Asunción, José Galindo created an artistic response – Las Escucharon Gritar y No Abieron La Puerta (They Heard Them Screaming and They Didn’t Open the Door). This was a sound performance in which 41 women were locked inside a small room shouting for nine minutes – the amount of time the girls at the Hogar Seguro spent screaming to be released while the classroom burned, before the police unlocked the door. Some of the mothers of the girls who died participated in the performance.

Stef Arrega of Ocho Tijax describes how the performance impacted her:

‘For nine minutes the women screamed out with all their might, these screams came from the gut. This was something that as I talk about, it gives me goosebumps, just remembering that event. Because, outside the room where this artist was holding the performance, we had an exhibition of paintings, portraits of the girls who died, the 41 girls. So it was immensely emotional to be listening to those screams of horror inside that space, while the portraits of all those girls where there, present.’

Regina’s process of artistic memory-making is designed to generate an impact within Guatemala and in the wider world about what happened, but it is also inherently personal, a way of making sense of the events for herself. Through it, she aims to ‘close certain wounds – and understand what happened’ in order to walk into the future.

Feminist artivism is associated with the use of bodies, music, words, and images in the public space to draw attention to gendered injustices on a societal scale. Arts are then used as a tool for conscientization (developing, strengthening, and changing consciousness), mobilization, and denunciation, and to disrupt the ‘common sense’ of everyday life in which even the most atrocious gendered harm is minimized, ignored, and denied. The families of the girls who died in the fire in the Hogar Seguro in Guatemala and the civil society organizations that support them actively use the arts to not only remember, but to mobilize and denounce; these are powerful acts of resistance that will remain, in the form of new memories and artefacts disseminated globally. As such, the arts – aided by social media platforms for dissemination – facilitate important transnational solidarity.

Those who feel threatened by these artivisms – the state, the military and their allies, particular groups of men, or conservatives – may try to take down the erected monuments as in Guatemala, or prohibit the plays or performances developed, as has happened in Peru, and even harass and threaten the activists, but this is increasingly counterproductive to their cause. Vianney Hernández, who lost her daughter in the fire in Hogar Seguro, understands very well that the government can destroy their memorial and obstruct the legal process, but it cannot erase her daughter’s memory. Through continuous creative campaigns, Vianney and her colleagues keep the pressure up and keep their daughters’ memory alive, as she discusses in the WRV podcast: ‘The government wants to erase our children’s memory and [I] can’t allow it as a mother looking for justice’. Vianney inextricably links obtaining justice in the courts with preserving the girls’ memory. Importantly, Vianney is surrounded by activists who will help her keep the memory alive, turning this initiative into an international campaign for justice in Guatemala.

Conclusion

Memorial arts, activist art, and feminist artivism are central to contemporary fights for social justice and women’s and LGBTQ+ rights. The trauma of historical violence reverberates into the continuous everyday harm done to the bodies and lives of women, girls, and LGBTQ+ communities. Much contemporary feminist activism makes the link between historical trauma and continuous political and domestic violence. This connection between past, present, and future not only unsettles and rewrites understandings of the past and offers a mirror onto the present, but in doing so it also allows for a reimagining of the future. Guatemalan performance artist Regina José Galindo sees her memory work as essential for creating a better future for her daughter:

‘Making memory in Guatemala, and not only in Guatemala but also in general, is necessary in order to become aware of the past, to manage the present and to have an idea of what kind of future can take shape. Especially when you have a daughter, you start to become aware that it is necessary to understand the past and to manage it.’ (Morris, 2017)

Through artivism, individual trauma is turned into collective resistance, mobilization, and counter-memory. While not without danger – given multiple activists around Latin America report violence and intimidation in response to their work – it is potentially transformative; a powerful rethinking of how politics is done, who perpetuates violence against women and girls, who produces resistance, and who, what, and how society remembers and values.

Bibliography

Boesten, J. (2022) ‘Transformative gender justice: criminal proceedings for conflict-related sexual violence in Guatemala and Peru’, Australian Journal of Human Rights, https://doi.org10.1080/1323238X.2021.2013701

Boesten, J. (2021) ‘A feminist reading of sites of commemoration in Peru’, in: Boesten, J. and H Scanlon, H. (eds.) Gender, transitional justice and memorial arts: global perspectives on commemoration and mobilization. Routledge Transitional Justice Series

Boesten, J. and Scanlon, H. (eds.) (2021) Gender, transitional justice and memorial arts: global perspectives on commemoration and mobilization. Routledge Transitional Justice Series

Burt, J.-M. (2011) ‘Accounting for murder: the contested narratives of the life and death of María Elena Moyano’, in: Bilbija, K. and Payne, L.A. (eds.) Accounting for violence. Marketing memory in Latin America. Durham and London: Duke University Press

Burt, J.-M. (2019) ‘Gender justice in post-conflict Guatemala: the Sepur Zarco sexual violence and sexual slavery trial.’ Critical Studies 4: 63–96.

Crenshaw, K. (1991) ‘Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color’, Stanford Law Review 43(6), pp. 1241–1299

Latin America Bureau and King’s College London (2022) ‘Women Resisting Violence podcast’, www.wrv.org.uk/podcast

Lugones, M. (2010) ‘Toward a decolonial feminism’, Hypatia 25(4), pp. 742–59

Morris, L. (2017) ‘A call to art: memorial’, BBC Radio 4, November, https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b09dy204

Rivera, M. (2017) ‘Nos duelen 56, una acción global por la justicia y por las niñas’, https://prensacomunitar.medium.com/nos-duelen-56-una-acci%C3%B3n-global-por-la-justicia-y-porlas-ni%C3%B1as-ce60f7e3196c