Migrant women experience persistent violence. The violence inflicted on Victoria Salazar, a Salvadorean migrant in Mexico, continued even after she was killed by police, through online reproductions and tabloid representations of her death. Victoria’s story is not unique. Tallulah Lines asks how we can we can contribute to mitigating violence against women and girls and avoid revictimising women through the way we remember their deaths and their lives.

This article was originally published as part of Redressing Gendered Health Inequalities of Displaced Women and Girls in Contexts of Protracted Crisis in Central and South America(ReGHID).

The police killed Victoria Salazar in Tulum, Mexico, on 27 March 2021, in a very brutal and very public way. Victoria, like many other Central American migrant and refugee women, fled her home country El Salvador precisely because of violence. This just adds to the tragic nature of her killing. The case has made headlines across the world, although these headlines are not always accurate: many claim that Victoria died, implying passivity or accident, rather than explicitly state the truth that she was killed by excessive use of police force.

Victoria’s killing was emblematic in a country which minimises and invisibilises the killing of women, and which is at best complicit in, and at worst encouraging of, police brutality, especially against the most marginalised members of society.

The way we represent the deaths of women – especially marginalised women – reveals a lot about our perspective and our intentions. So how should we best honour and remember Victoria, in a way which respects her humanity and dignity, but does not shy away from telling the truth about the violence she experienced? Visual methods are a powerful and important way of doing this, though they are often also controversial, even among artists and activists themselves.

Gender-based violence is a major reason why Central American women leave their homes

Victoria was a single mother to two daughters, who came from an impoverished and marginalised community in El Salvador. Determined to provide a better and safer future for her daughters, she made the difficult decision to leave El Salvador and travel with them to Mexico, where she sought asylum, and worked as a cleaner in a hotel in the hipster town of Tulum in the Riviera Maya.

According to her application for asylum, Victoria left El Salvador because the violence there caused her to fear for her life. This is an all too common story among Central American women on the move. El Salvador in particular has occupied the top or close to top spots for femicide in the world in recent years; it also consistently ranks highly for gang violence and murder. Added to this is structural and economic violence which leaves women like Victoria from marginalised communities with few opportunities to find dignified work – this was another reason why Victoria left El Salvador.

Women on the move experience persistent violence – especially in Mexico

Unfortunately, when people on the move leave their home countries and begin their journeys north, they remain at great risk of violence, especially as they pass through Mexico. This violence comes from many sources, and the lethal violence Victoria suffered at the hands of police is not an isolated incident.

For years, Mexico has become increasingly hostile towards migrants; in 2019, the threat of trade-related sanctions from the USA was the impetus for increased militarisation of the Mexican border and growing state-endorsed hostility towards migrants. That year, of the 599 complaints of abuses against migrants received by Mexico’s Commission for Human Rights, the majority were against the federal police.

This violence committed against people on the move in Mexico continues today: they are consistently ‘exposed to rape, kidnapping, extortion, assault, and psychological trauma’, perpetuated by state actors like the police and immigration officials, as well as by non-state criminal groups, though migrants have commented that the violence they experience is so ubiquitous it is hard to tell the difference between law enforcement and criminal groups.

Women are at risk of all of the violence above, as well as facing particular threats because of their gender. Between 60% and 80% of girls and women are raped or experience sexual assault while migrating north from Central America. In fact, the risks are so high that many are told by their coyotes (people smugglers) to take contraceptives before migrating to avoid pregnancy; obviously, this does not reduce their risk of rape, assault, or contracting STIs. They are also at high risk of being trafficked into prostitution.

The risks for people on the move – especially women – have increased exponentially during the pandemic. For example, rates of people trafficking in Quintana Roo – the state where Tulum is, incidentally – increased by 265% in 2020.

Migrant women were already known to be at high risk of xenophobia, often invisibilised, discriminated against or stigmatised in the countries they migrate to: in the context of Covid-19, this has increased. Many migrant women in Mexico have also found themselves in even more vulnerable positions because Covid-19 policy responses have restricted movement, stopped them being allowed to enter shelters, and cut off already limited access to sexual and reproductive health services and supplies.

For Victoria’s daughters, both minors and now left alone in Tulum, the violence they have experienced and the threat of violence they continue to experience has not ended with the killing of their mother: days after Victoria was killed, her partner was arrested on charges of sexually abusing one of Victoria’s daughters, and Victoria’s other daughter went missing, apparently in hiding for fear she would be deported.

How can feminist activists and artists truthfully honour Victoria’s memory?

When the news of Victoria’s killing broke, feminist artists were enraged, frustrated, upset and deeply sad. They immediately began to create artwork and upload it to social media – an important site for contemporary feminist activism in Mexico. Many feminist illustrators based their artwork on a widely circulated image of Victoria’s last moments, in which she is, effectively, being killed.

The image is certainly shocking: Victoria is on the ground being brutally restrained by a police officer. It perfectly captures the violence and repression of the police, which is so often invisibilised or normalised. The image evokes anger, shock, horror and elicits a deep empathy for Victoria. It is in many ways a very important image.

However, almost as soon as feminist illustrators circulated their interpretations of this image, they began to question themselves: was sharing this image continuing to enact violence on Victoria, and continuing to degrade and humiliate her, even after her death? Several artists removed the illustrations they had created, though some continue to believe it is an important image to share, and it was painted onto the wall of Cancun’s town hall during protests there.

The range of visual methods used by local feminist collectives in Tulum during the protests immediately following Victoria’s killing strikes a good balance between exposing the violence and anger of the case, and honouring the humanity of Victoria. Thanks to these methods now, two weeks later, Tulum looks very different, and there is no hope of invisibilising what happened to Victoria.

The town’s main street, monuments and town hall are completely covered with feminist and anti-police graffiti. The sheer quantity of graffiti is very impressive. This serves to expose both the reality of Victoria’s death, and the definitive presence of the feminist movement, embodying the much-repeated feminist slogan ‘nunca jamás tendrán la comodidad de nuestro silencio’ (never again will you have the comfort of our silence).

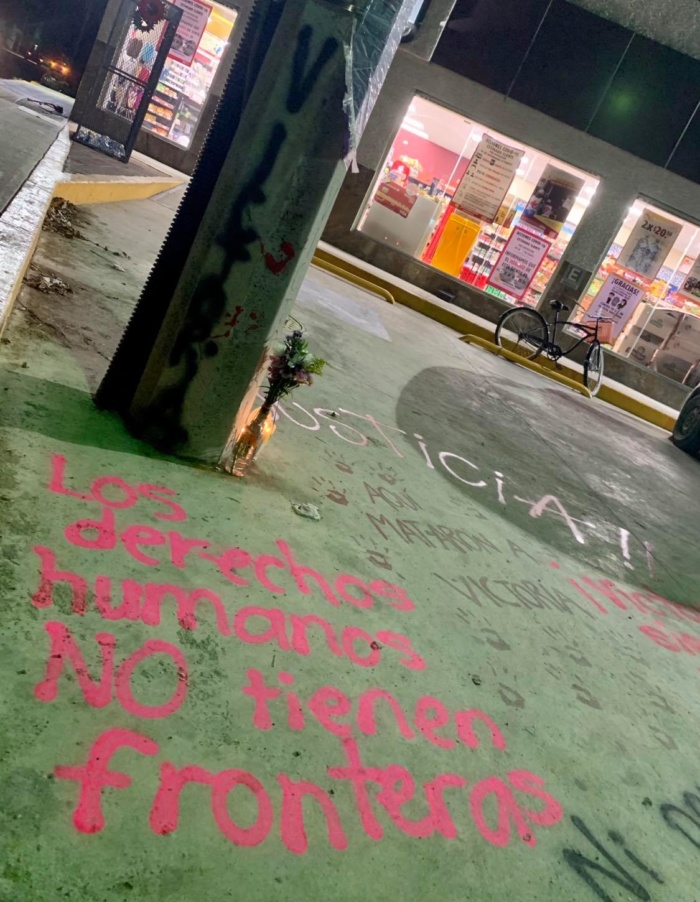

The spot where Victoria was killed is an eerie and ominous place now. The words ‘aquí mataron a Victoria’ (they killed Victoria here) are painted in blood-red on the concrete, framed by red hand prints, and flanked by more graffiti demanding justice and asserting that the police killed Victoria. Activists have placed flowers and candles at the spot.

Finally, on the wall of the town hall, which faces the main street, is a 2x3m painting of Victoria. Victoria looks glamorous, in large silver earrings and pale pink glossy lipstick. She engages the viewer, with large dark eyes, lightly smiling. The image is adapted from an illustration by Tijuana-based artist @sirakiry, though the colours are warmer, and Victoria is framed by marigolds and candles, staple elements of Mexican day of the dead shrines. The words ‘Justicia para Victoria Salazar’ (justice for Victoria Salazar), and ‘Los derechos humanos NO tienen fronteras’ (human rights don’t have borders), are written on either side of the portrait.

We originally painted this mural in an hour and a half during the 29 March protests, protected by other activists who formed a crowd around us to shield us from police. Painting the mural created an impact during the protest, and continues to have longer term impact.

The mural was vandalised with political graffiti just days after we painted it, like other feminist murals in Quintana Roo. We returned to repaint and improve it, committed to keeping the case of Victoria in the public eye.

The graffiti in Tulum’s town centre and at the spot where Victoria was killed highlight the violence and brutality of Victoria’s killing, which is deeply important, since violence in many forms is an inescapable reality in the lives of Central American women forced to flee their homes and migrate through Mexico, and it should not be invisibilised or normalised. We chose to combine this with a bright, vibrant and warm mural, using an image which showed Victoria in a way we imagine she would like to be remembered. We hope that this combination represents Victoria’s life and her death with the respect and dignity she deserves.

Tallulah Lines is a PhD candidate in Politics at the University of York and Research Associate at the Interdisciplinary Global Development Centre, University of York. Her PhD deals with the role of art in feminist activism in Mexico. She is working on two research projects at IGDC; Gender and Health Systems in Low and Middle-Income Countries after Covid-19, and Redressing Gendered Health Inequalities of Displaced Women and Girls in Contexts of Protracted Crisis in Central and South America. Tallulah is interested in using the arts and creative methods within academic research and has carried out projects exploring the relationship between art and research in Mexico. She is an artist and co-founder of Las Iluministas.

This article was originally published as part of Redressing Gendered Health Inequalities of Displaced Women and Girls in Contexts of Protracted Crisis in Central and South America(ReGHID), an interdisciplinary and international consortium that builds new research and advocacy for more effective and inclusive attention to the sexual and reproductive health needs and rights for displaced women and adolescent girls from Central America and Venezuela. ReGHID is funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) at UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) through the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) to address development-based approaches to protracted displacement.