São Paulo, 23 November 2022. At the COP27 meeting in Egypt, president-elect Lula enjoyed a triumphant few days, being greeted by foreign heads of state and multilateral organisations with respect and relief as he declared, ‘Brazil is Back’.

Four years of Bolsonaro’s extreme rightwing ideological policies, his deliberate lies and encouragement of the rampant destruction of the Amazon had turned Brazil into a pariah state, unwelcome and shunned at international meetings.

Yet in Brazil, many of the actual president’s most fanatical supporters refuse to believe he lost the election and are determined to overturn the result. They claim that Lula`s victory was the result of fraud and are demanding military intervention. His party, PL, Partido Liberal, egged on by Bolsonaro, has petitioned the TSE, the national electoral authority, to have the result of the second round, when Lula won, annulled, claiming that thousands of voting machines were irregular.

The head of the TSE, Supreme Court judge Alexandre Moraes, Bolsonaro’s bête noir, swiftly applied a virtual checkmate, ruling that the results of the first round, when the PL elected 99 federal deputies and 13 senators, their best result ever, should also be reconsidered, because the voting machines used in both rounds were the same. The PL’s allegations contradict the results of internal and external monitoring of the elections, which found them to be fair and honest.

These two parallel worlds now exist side by side. On the one hand the president-elect and his transition team are planning their government, once Lula takes office on 1 January, as in a normal country, while on the other hand groups of hardline Bolsonaristas are camped on roads and outside army barracks demanding military intervention.

In some places they have resorted to terrorism. In Mato Grosso a group of masked armed men attacked and burned lorries to block the BR163 federal highway near Sinop, and burned down toll gates near the town of Sorriso. A busload of people on their way to hospital for treatment was turned back, including a small boy who needed an urgent operation to save his sight after an accident.

In Santa Catarina the police compared their activities to the ‘black blocs’ an anarchist group which appeared in São Paulo during the 2013 anti-government demonstrations. The western Amazon state of Acre, which relies on one highway, the BR364, for all its supplies, is now facing shortages due to the blockades taking place in the neighbouring state of Rondônia.

These blockades are being maintained not just by the complicit silence of the president, who so far has neither acknowledged the election results nor complimented his successor, but also by funds and equipment supplied by individuals and companies who support Bolsonaro. Far from being the spontaneous acts of citizens moved by indignation, they are in reality the work of saboteurs paid to create confusion, uncertainty and ultimately civil unrest, with the aim of provoking military intervention.

The divisions deliberately sewn by Bolsonaro during his 4 years in government will not easily disappear. Politics has become aggressive, sometimes violent. In the south of Brazil, where he received many millions of votes, and some towns voted almost 100 per cent in his favor, social media campaigns are urging boycotts of restaurants and companies known or alleged to have supported Lula.

Individual politicians who openly supported the president-elect have been verbally attacked. Former president of the lower house Rodrigo Maia, on holiday at a resort in Bahia, found himself surrounded by aggressive men and women shouting ‘ladrão’ (thief). Reporters from mainstream media have been physically attacked by bolsonaristas who get their news exclusively from social media and do not believe in other versions of events.

Meanwhile Bolsonaro’s silence extends to his presidential agenda. He has literally vanished from sight, gone AWOL. Vice president Hamilton Mourão has taken over formal duties like receiving new ambassadors, while General Braga Neto, his election running mate, makes regular visits to the mansion in Brasilia, erstwhile campaign HQ, to give pep talks to coup conspirators who gather there.

Officially Bolsonaro’s absence from government, which has now lasted almost three weeks, has been attributed to health problems, including a leg infection. But as commentator Fernando Gabeira ironically observed, after news that Lula has been banned from speaking for a week by his doctors because of a lesion in his vocal cord, ‘Lula can’t speak because he has a problem with his throat, but Bolsonaro can’t speak because of a problem in his leg?’

Social media is alive with rumours of coups.

Veteran journalist Luis Nassif wrote: ‘this festival of leaks, audios and news items aims to create coup plots among the military.’ He said the next few days will reveal the role of the Armed Forces, either returning to their professional behaviour or giving in to a new coup impetus. He believes that this ambiguity will only be undone once Lula takes office, with the renewal of the armed forces high command and the retirement of those who endorsed coup movements.

At the moment, the resounding silence of the Armed Forces, after months of querying the electoral process and releasing ambiguous notes about the possibility of fraud, has not helped to restore normality.

That is the parallel worId of Bolsonarismo, fostered and encouraged by the president himself, hiding out in the presidential palace like a man already on the run.

What could be a deciding factor in deflating the protests in the ‘football nation’ is the World Cup, particularly if Brazil wins its first few games. It is also being seen as a chance to take back into general ownership the Brazilian flag, appropriated by bolsonaristas as a political statement of their rightwing patriotism. ‘The national colours belong to everyone, not to one political party’, said Lula.

In the other world of normal political process, Lula’s rather unwieldy transition team, now numbering over 300, is poring over the books, and discovering that Bolsonaro is leaving behind a ‘terra arrasada’ or waste land of empty coffers and essential programmes left without funding. The federal police has had to suspend the issue of passports, and the distribution of drinking water to needy families in the semi-arid Northeast, and free medicines to patients with chronic health problems all over Brazil, has been stopped.

The Bolsonaro government reduced the budgets of the Health and Education ministries, although the effects of the pandemia meant that they needed more, not less money, and cut those for environment, science and culture to almost nothing, in order to finance what has become known as the ‘secret budget’, billions of reais released to his supporters in congress to be freely spent on projects they calculated would win them votes.

The mainstream press, which was consistently muted in its criticisms of this irresponsible economic policy, is now accusing Lula of lacking fiscal responsibility even before he has taken office, because he says that social responsibility is just as important, and insists that his priority is ending hunger.

It is obvious that there will be no honeymoon period for the new government, under attack from resentful Bolsonaristas who claim the election was stolen, and a conservative press, more heedful of market forces than the needs of the hungry.

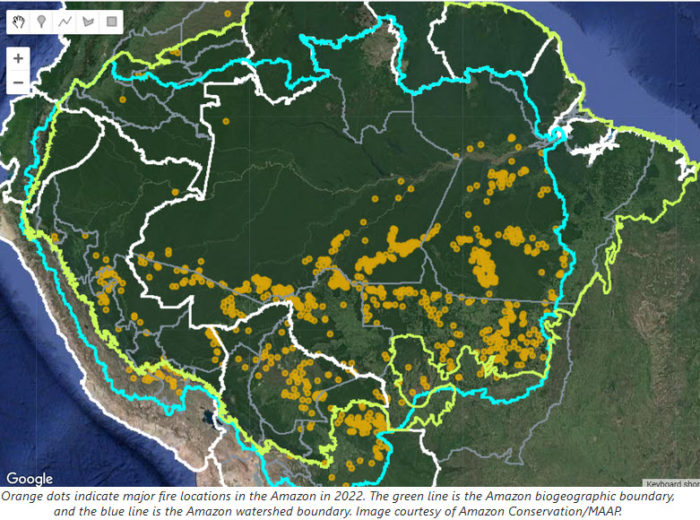

Bolsonaro is also leaving behind a time-bomb in the Amazon, which Lula has promised to protect. Record deforestation is taking place, even in the last months of the year when it is traditionally less. Unchecked invasions of public forest areas, national parks, and indigenous territories are increasing.

Activities like illegal mining and logging are now the preserve of organized crime, which has become rampant in the region. Dealing with this complex situation will present one of the biggest challenges to the new government. When Lula takes office in just over a month he will have the goodwill of most of the international community, but he will inherit a divided nation with huge social, economic and environmental problems.