This new documentary by director Marcos Colón shows the Amazon at its most beautiful even as it is threatened by conflict. It won the prize for Best Cinematography at the 12th Filmeambiente (Environmental Film Festival) in Rio de Janeiro.

São Paulo (SP) – Thursday 9 November. The documentary Pisar Suavemente na Terra (Tread Gently on the Earth) by Brazilian director Marcos Colón, son of a North American father and a mother from Piaui, won the prize for Best Cinematography at the 12th Filmambiente– the International Environmental Film Festival. The festival, which took place in Rio de Janeiro, screened 25 productions, long and short documentaries, animations, and fiction from 11 countries.

‘Beautiful photography of the river, its people, and life by the river. The powerful visual representation of the beauty and the conflicts of the people of the Amazon was hard-hitting’, stated the jury.

The victory was deserved. Pisar Suavemente na Terra is, first and foremost, a powerful visual experience. Images that have been made almost routine in our hyperconnected world emerge as majestic, rallying, moving, or shocking.

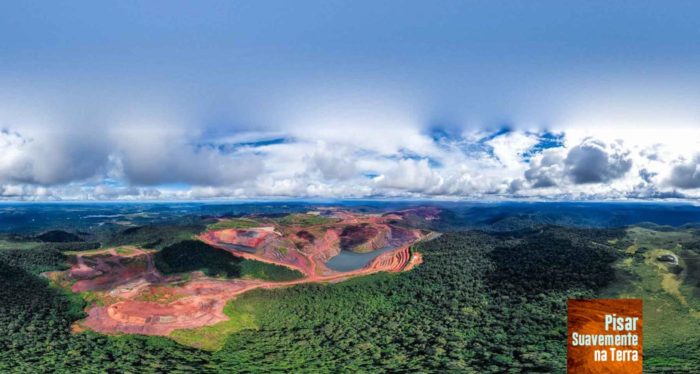

Seen from above, the deforested area around the Alcoa bauxite mine in Juriti, Pará, suggests the track of a space robot on Mars, or a red desert; the ore train that cuts through the night in the jungle, awakening a village fraught with dread, is no different to the subway train that cuts through the northern zone of Rio de Janeiro. Everything seems to be on a continuum: from the soy shipping port in Santarém to the Belo Monte Hydroelectric Power Plant; from the Carajás railroad of Bom Jesus in Tocantins to the scenes of villagers slowly peeling cassava.

The Amazon that we see is a magical place and unparalleled. We are transported from the swarm of tuc tucs (motorcycle taxis) of the public market in Peru to the riverside homes in Pará built on stilts; from the vultures eating the garbage in the market in Iquitos to the footprints of mining on the Tapajós River, in Itaituba, Pará.

This is an Amazon wounded by death, but, in contrast, there is the calm, considered routine of three families, each an inspiring pocket of resistance: that of Kátia, chief of the people of Gavião Akrãtikatêjê, on the Mãe Maria indigenous land; that of Manoel, chief of the Munduruku people of Ipaupixuna (PA); and that of José Manuyama, a teacher of Kokama origin, from Iquitos, Peru.

The impact of these interviews intensifies as the film progresses. Professor José Manuyama, from Peru, appears conscious of two points of tragedy. ‘I think this is common in Brazil,’ he says, ‘the felling of thousands of hectares, but here no.’ He has discovered that 2,000 hectares of virgin forest have been devastated in his region. However, the inaction of the government is the same on both sides of the border; the use of mining dredgers is illegal in Peru, but in Brazil it is no coincidence that it has been permitted for the last four years.

In both countries the diagnosis is exactly the same. Chief Manoel clearly defines the continuing effects of new, ‘modernizing’ ventures in the name of progress: ‘They bring only destruction, drugs, prostitution’. For José Manuyama, they import ‘misery, poverty, contamination, corruption’. For writer, poet, environmentalist, and indigenous leader, Ailton Krenak, this driving force of devastation is not a coincidental effect of modernity: ‘It is a key product,’ he emphasizes.

In the name of progress

The film does not neglect detailed research. It includes the dramatic testimony of Kátia Akrãtikatêjê about the siege suffered by her family, her father and her mother with four small children, at the beginning of the 1980s, in Tucuruí.

To force the inhabitants out of their village, armed men with machine guns surrounded their dwellings for weeks on end. Kátia was only 9 at the time and did not understand what they were doing there. Her father, Payaré, decided to resist. Everyone else gave up, leaving on a truck to never be seen again, but the family stayed.

The miners used dynamite to divert the river. When three men tried to behead her father, the whole family had to hide in the forest. When they eventually left, they lived as beggars in the city. The saga of ‘humiliation and prejudice’, Kátia explains, was so profound that they were forced to stop using their indigenous names.

In the midst of the already serious problems afflicting native peoples (predatory mining, monocultures, illegal prospecting, predatory exploration for petroleum, the extraction of wood and the consequent deforestation, and the construction of mammoth hydroelectric power plants), the film interposes surprising moments of calm, like the visit of the Peruvian citizen to the Covid Cemetery in Iquitos, although this, too, is symptomatic of the negligence of the State and the vulnerability of the inhabitants of the forest. The documentary was filmed in Peru, Colombia, and Brazil.

‘Humanity creates layers of difference, until it is reduced to a club, a closed club. And the outsiders, the rest, can all go to hell’, says Krenak. ‘I don’t want anything to do with this part of humanity that chooses to die!’

Throughout Pisar Suavemente na Terra, there is a conscious striving to emphasize humanity. This is a principle of the film’s director, who lives in Tallahassee, Florida, and is a professor on the Public Health program at Florida State University. Against the lies of a system that moves from one fetish to another, from one promise of wealth to another, Kátia Akrãtikatêjê shows how she has no need to accumulate gold or sell the assets of the forest for an unknown form of well-being. ‘I have my passion fruit, my cassava’.

Without water there is no Amazon

There is no wealth awaiting the peoples of the forest at the crossroads of development, which, according to the French philosopher Bruno Latour, is based on the opposition between nature and culture. ‘Modernity is synonymous with social ruin’, concludes José Manuyama. Stripped of the illusion of finding Paradise, the film mines the vastness of the consciousness of the world.

It is interesting to note how the presence of water becomes a dominant visual and narrative force in the film along its way, encompassing four river basins. ‘Water is imposed on the narrative,’ says Colón, ‘and it is very welcome. As you know, the Amazon is ‘amphibian’, and we have great writers that narrate this state. Milton Hatoum himself has an amphibious literature that describes this process of Amazonian life. Without water, there is no Amazon, and it has become an essential element of all the issues related to it: the contamination in Peru, in Brazil, the water tables, the miners, the subsoil.’

Colón speaks out against a kind of ‘biocultural amnesia’ in relation to the territory. ‘Thinking about the Amazon based on its peoples involves thinking about the Amazon based on what is important to them: ways of surviving, the water, the forest, the biodiversity, the local culture. Yet we generally think of it as a commodity, to be traded, an object of exploitation.’

The film begins with an image from the region where, in June, the British journalist Dom Phillips and the Brazilian indigenist Bruno Pereira were murdered, in Atalaia do Norte, in Amazonas. The images are accompanied by the words of Ailton Krenak, one of the most developed voices of contemporary consciousness of the dilemmas of the planet in a time of mass acquisition and consumption.

It is possible, based on the obvious findings of devastation, to see this film as a mere denunciation, a protest, a warning. But Pisar Suavemente na Terra is above all a philosophical film, a dive into perceptions of how the celebrated myth of progress and development on the Brazilian and Peruvian Amazon operate in practice. Interconnected by the voice and ancestral understanding of Ailton Krenak, these reports of resistance present other ways of existing and walking through the world.

There are plans to screen the film in several UK universities early in 2023. For details, please contact LAB.

Jotabê Medeiros is from Sumé in Paraíba, but as a child and teenager lived in Cianorte, in the interior of Paraná. Journalist, writer, and culture reporter for 35 years, he is the author of the books “O Bisbilhoteiro das Galáxias”; “Belchior – Apenas um Rapaz Latino-Americano”; “Raul Seixas – Não diga que a canção está perdida”; “Roberto Carlos – Por isso essa voz tamanha”; and the family autobiography “O Último Pau de Arara”.