Main image: Aerial photo of agricultural land near Ipiales, Colombia. Photo by Luis Eduardo Bernal M. 2009.

In February 2019, Darío Acevedo was appointed president of Colombia’s National Center for Historic Memory (CNMH) whose objective is to discover the historical truth of the country’s armed conflict ‘through the recuperation, conservation and divulgation of the victims’ plural memories, and through the state’s and aggressors’ duties towards memory in the events of the violations of rights in the context of the Colombian armed conflict’. His appointment received mixed responses: conservative politicians and the military welcomed him while academics, grassroots movements of victims and voices from the political left complained about Acevedo’s political leanings and distrusted his involvement in the project.

The criticism was not without some justification. Acevedo publicly denied that there had been an armed conflict in Colombia. Also, as vice dean of the Faculty of Human and Economic Sciences, he vetoed courses on fascism and Marxism. He was a highly controversial choice to lead an institution whose explicit aim is to build a national history including the different narratives of the victims of the conflict. Acevedo’s historical relativism and unwillingness to deal with complicated topics were not well received by several groups of victims who, after expressing their concerns, withdrew the documentation they had given to the center.

The process of truth-seeking, in a country fragmented by more than half a century of warfare, murders, kidnappings and massacres, is necessarily painful and contested, especially since it is the state—considered by many to be an aggressor—that is in charge of carrying out this process. The gradual exclusion of groups of victims will inevitably lead to bias where the story is told only by those people who are allowed to recount it.

The latest controversy surrounding the CNMH is their invitation to the military and groups of cattle ranchers to be included in the narratives of the country’s memories. Their association, FEDEGAN, has been invited to write a book, documenting the actions against the 11,000 ranchers it has identified as victims of the conflict. While it is true that these groups, too, were targeted in the war, they were also actors in it. The military are representatives of the government forces, while the cattle ranchers created and financed paramilitary groups to fight the guerrillas, which eventually became involved in the drug trade.

Paramilitary enforcers

Cattle ranching is an important part of Colombia’s economy and occupies 80% of the country’s agricultural land. The largest 1% of the landholdings in Colombia account for 81% of farmland (data from 2018). In farms over 1,000 hectares, 87% of the land is used for cattle ranching. This makes Colombia one of the most unequal countries in the world in terms of land ownership. It also makes the association of cattle ranchers a strong power in Colombia’s rural development.

The conflict in Colombia still is a conflict over land. And several representatives of FEDEGAN have had ties with paramilitary groups that they used to defend their lands against the guerrillas. They also used them as instruments to increase their landholdings by intimidating and expelling smaller landowners. Jorge Visbal, former president of FEDEGAN is currently in prison for his links to the paramilitary. Jose Miguel Narvaez, a close assessor to the current president of FEDEGAN, was sentenced to 30 years in prison. And there are several ongoing investigations into other leaders of FEDEGAN.

FEDEGAN had more considerably more power and influence to act during the armed conflict than smaller communities of campesinos, because their control over such a large proportion of the land translated both into wealth accumulation and political influence. This enabled them, with partial acquiescence of the state, to establish parallel military units to serve their interests.

With many smaller groups of victims excluded from the historic memory project, while cattle ranchers are included, the inequality that has been at the root of Colombia’s conflicts is being replicated. Now it is not just a fight for access to the land, it is also the struggle to determine whose voices will write the narratives of memory of Colombia. The tension lies between giving space for the complexities of multiple narratives or creating a single, official history.

Alternatives and other voices

Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica. YouTube. 15 November 2018.

Nevertheless, future prospects are not necessarily bleak. Between 2009 and 2019 the CNMH managed to develop relationships of trust with different groups of victims, enlisting respected academics and learning from experiences abroad to publish over 110 books, and over 70 documentaries, podcasts and digital special reports collecting experiences from different victims in the different regions.

Even more than the bibliography thus generated, these exercises of truth-seeking have enabled an appropriation of the past by different communities, so that they can understand the conflict from the national, local and personal perspective. This process is important as a first step for the return of displaced people to their territories.

The book Sin territorio no hay identidad: Memorias visuales del resguardo indígena Wayúu de Nuevo Espinal (CNMH, 2019) which narrates the memories of the Wayuu Indigenous group is organized into three different but interrelated perspectives: territory, culture and spirituality. These are fundamental components of their identities.

For us not having a defined territory is not having an identity, we don’t consider the identity card as our first identification, our identification is our territory. So if we meet a fellow traveller on the road and he asks, “where are you from?”, We answer “from this territory”, “from this community”, “from this clan”, and that is how they know who we are.

Wayuu community member.

The Wayuu live in the northernmost department and have been displaced by coal mining and subsequently by drug traffickers. So, they have had to adapt to their new settlements. One of the traditions they had lost with displacement was Yanama, which is voluntary communal work in the fields – a practice they are now trying to restore. Other things have changed, such as rearing goats, which they have had to replace with poultry and pigs. Although they cannot recover all their former practices, the process of recognizing and missing the past also helps to reconstruct memory.

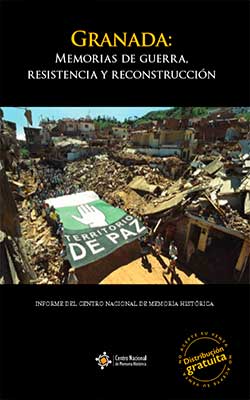

Another example of how recounting their own stories empowered a group of people to assert ownership of their lands is contained in the book Granada: Memorias de guerra, resistencia y reconstrucción (CNMH, 2016) which tells the story of the town of Granada in Antioquia. Due to its strategic location between Medellin and Bogota, the town was besieged by both paramilitaries and guerrillas. They suffered more than 30 massacres during this period.

Many inhabitants decided to look for opportunities elsewhere and become part of the more than 8 million internally displaced within Colombia. Today, there is a project of returning and repopulating the town.

The book which tells the story of Granada was the product of discussion groups, interviews, personal testimony and archival work. Memories of resistance revolve around how the community maintained its social fabric – through reinventing the public sphere, adapting to curfews by many people sleeping in the same home, keeping the town’s government working even when it seemed futile and physically rebuilding the town while still in the crossfire of the war. These experiences illustrate the battle for the meaning and resignification of spaces – will they be places of fear or places of resistance and resilience?

Finally, a third publication Arraigo y Resistencia: Dignidad campesina en la región Caribe (1972-2015) (CNMH, 2015), focusing on the country’s Caribbean region, demonstrates that retaining a strong sense of property rights is the main weapon of resistance for campesinos against the dispossession of their lands by external enemies.

In communities where the state has not been present to register and legalize landholdings, property rights have been maintained through oral tradition. When communities are fragmented, their histories, identities and relationship to their land are also fragmented or lost. The collection and publication of these experiences, therefore, serves as a permanent reminder of the collective wrongs experienced by the communities and as validation for resisting new attempts to marginalize them.

The publications of the stories of the Wayuu, the town of Granada, and the Caribbean indigenous show how memory is a claim to territory, to community, and to both history and the present. These are examples of the ways memory can preserve and restore efficient ways of organization and reaffirm the sense of identity through community. It is also the first step in the generation of economic opportunities for these communities

Conclusion

Despite their partial undermining by the state, it will be hard to destroy the projects of recovery of memory that have been established by the collectives of victims. The theft of the memory and lands from the victims occurred over a protracted period of time. More recent experiences are not as easy to erase, due to their freshness but also because the associations of victims are already joining hands to conform more resilient networks. Victims’ groups have developed tools for memory building and dissemination in order to understand their own stories in relation to their own communities, others and the environment, which are the keys to making sense of the here and now.

Owning territory is not just the physical ownership of the land, but also ownership of the historical narratives related to it. Recovery of memory is a democratizing force that can help Colombia understand itself as a country and that its history is founded on regional and racial inequities. Only once this is recognized, will Colombia be able to project itself for the future as a plurinational country.