Cúcuta, Colombia, lies halfway along the country’s border with Venezuela. Pendular migration between the two countries happens here every day, and it has become one of the most used migratory paths in Latin America. It serves as an escape from poverty and despair for thousands of Venezuelans crossing the border to Colombia each year.

Venezuela was once a receptor country for Colombians fleeing from the War on Terror in the 1980s. Since 2015, however, more than a sixth of Venezuela’s population is estimated to have left the country. This is the first time, apart from during wars, that a crisis of these proportions has engulfed one of the wealthiest countries in the subcontinent. The majority of those fleeing head to Colombia.

In 2020, at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, both Colombia and Venezuela closed their borders and the migratory flow decreased significantly. However, the Pandemic only accentuated the Venezuelan crisis that has been worsening since the country’s economy started shrinking in 2013. Between 2014 and 2020, Venezuela’s GDP has declined by 74%. More than three-quarters of Venezuelans live on less than $1.90 a day, situating them below the extreme poverty line.

Nowadays it is estimated that 2,000 people are leaving Venezuela each day through so-called trochas, while formal crossings like the one at Cúcuta have been closed. After all, restricting movement only diverts it to informal corridors. The use of trochas has become the only option to flee Venezuela by foot since the borders shut. There are now almost 300 unauthorised crossing places along the 2,219 km border.

Authorities are well aware of these routes but, rather than policing them, use them for their own gain. Military personnel as well as criminal gangs and guerrillas from both sides of the border have exploited this illicit market by extorting payment from those who seek to cross. They even charge migrants extra for each piece of luggage they carry. This market relies on the lack of law enforcement at the border, aggravated by the pandemic.

Alans Peralta is the coordinator of Caminantes Tricolor, an NGO that offers assistance to Venezuelans and returning Colombians at the Colombian side of the border. He spoke to LAB about the situation of migrants along this border during the pandemic.

Peralta explained that Covid-19 was at the bottom of the list of concerns for the Venezuelan migrants he works with. He pointed it out that this contradiction reflects peoples’ experience of trying to survive in their country:

‘They are obviously looking for a better future destination. They look for hope, people cling to hope. In Venezuela there is no hope. However, the people do not think of Covid as Venezuela’s main problem, despite the fact that there is no public policy and there is no design; there is no vaccination plan; despite the fact that this government will not give assurances. Despite everything.’

People are aware of the pandemic, but the population have long considered a devastated, corrupted and overwhelmed health service to be old news.

Whole families, not just the young

The dramatic shift in the profile of Venezuelan migrants in recent years shows how the Venezuelan crisis is evolving. According to Peralta, in 2018 the standard profile was a young man between 14 and 22 years old ‘with a defined destination’ and a ‘contact network’ at the other side of the border. For several months now, whole families with children have been migrating without a defined destination and without relatives on the other side.

A report from the Migration Policy Institute (MPI) confirms that the number of families leaving Venezuela has doubled between 2017 and 2021. Peralta explained that the change is because ‘Migration today moves because of hope, not security’. He interprets this as a consequence of the worsening situation in Venezuela, where people’s despair is driving them to take great risks with the sole purpose of finding better living conditions on the other side.

He also insisted that help does not end at essential resource assistance – the provision of primary healthcare, food, hydration and clothing. While Caminantes recognises that the Colombian Government’s resource assistance will always be necessary, Peralta believes this is not a long-term solution to Colombia’s migration problems. To be effective, emergency aid must be accompanied by socio-economic integration.

Colombia’s response

Colombia took the unusual step of opting out of a regular asylum seeking system, even with staggering rates of migrants being hosted by the country, which escalated from less than 100,000 to 1.7 million in less than five years. The country dealt this vast number of arrivals without setting up a sea of overcrowded tents. The Government implemented a massive regulation system for Venezuelans, by which one million immigrants have obtained a biometric identity card. The card allows them to live and work in Colombia – which facilitates socio-economic integration. This policy replaces an asylum-seeking strategy with an inclusive migrant policy. The policy received great praise from the UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency and the International Organization for Migration, while the agencies themselves have played a minimal role in this migration crisis.

The benefits of regularisation are clear. Besides the humanitarian advantages, this year Venezuelans contributed to a 0.33 per cent increase in Colombia’s GDP, stimulating the job market in challenging times. The World Bank also announced that for every half a million people of working-age arriving in Colombia, Colombia’s GDP increases by 0.2 percentage points.

Despite the regulation system, however, many Venezuelans end up in informal job positions – including those with higher education – and in a vulnerable legal situation, which has caused many Venezuelans to return to their country.

Caminantes Tricolor works to help integrate Venezuelan migrants and to find them a more secure position. They start by helping them join the local economy and help the Colombian Government to establish policies to contribute to this measure. They have helped up to 300 migrants a day for more than two years. Caminantes Tricolor continues to work with the Colombian Government to make Migration Profiling the official policy.

However, Peralta believes that a big part of the solution relies on a simple but resource- and time-consuming strategy: Migration Profiles. It is a method based on categorising each individual according to their background.

Usually, in migration crises, a lot of cultural and language barriers arise when migrants are introduced to the job market. In Colombia’s case, where these barriers are less prominent, the tools the Migration Profile strategy provides are more practicable. By profiling migrants on their skills and studies, they can more easily enter the job market. Nonetheless, it is a tool that the Colombian government has yet to implement on a national level.

Rising xenophobia

More concerning is that MPI polls from Colombia between 2019 and 2020 show that up to 53 per cent of Colombians believe that Venezuelan migrants have increased the country’s insecurity, despite the fact that there is no evidence that the massive migration wave has affected crime rates.

Xenophobia is no new phenomenon in Latin America. However, the pandemic has changed the ways it manifests itself. The surge in job instability during the crisis has fuelled Colombians’ rejection of Venezuelan migrants. Negative perception rates have doubled since 2018 and reached 69 per cent in 2021.

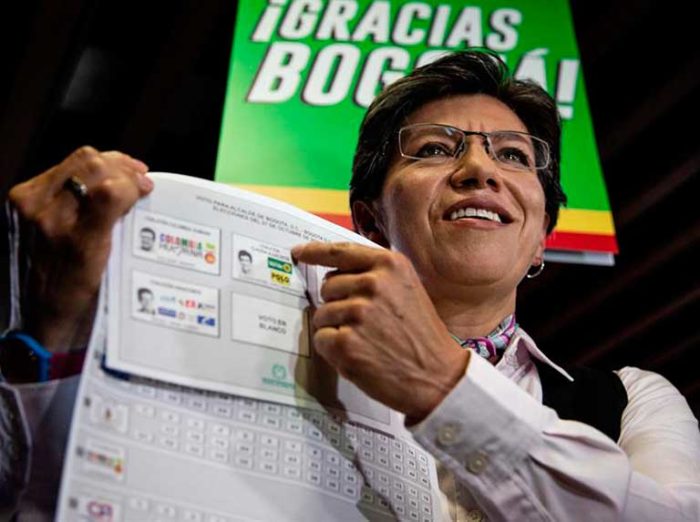

Local politicians have few incentives to refrain from demagogic messages which amplify the fears on which xenophobia feeds. Migrants are the perfect scapegoat when it comes to finding external causes for the crisis. Bogota’s mayor, Claudia López Hernández, recently made xenophobic remarks against Venezuelans, in marked contrast to her usual progressive views.

Colombia’s Government faces an immense challenge in managing migration. Xenophobia is on the rise and the relationship with their neighbour is extremely delicate. NGOs such as Caminantes Tricolor offer valuable help, and mitigate some of these difficulties. Much remains to be done to alleviate the suffering of the vulnerable who are still the ones who suffer and the future of Venezuelan migrants without damaging Colombia’s population.

Antonella Navarro is an International Relations student at the University of Essex. She is passionate about understanding Latin America’s politics, migration and economic development. She has been working with LAB for the past eight months, her research centred on the Venezuelan humanitarian crisis and the project ‘Voices Of Latin America’.

Main image: Venezuelans cross the Simon Bolivar International Bridge into the border city of Cúcuta, Colombia, October 2018. © UNHCR/Fabio Cuttica