Once regarded as an ‘island of peace’ in a troubled region, Ecuador sits at the heart of the complex migratory flows that dissect Latin America’s Andes. But the eruption of violence that has upended Ecuador since 2016 may have spun the country onto a path towards an exodus of its own.

Main image: Deilys fled Venezuela to Ecuador with her family. Thanks to the Graduation Model courses, she has been able to build a business making and selling vegan desserts which has allowed her and her family a regular income and a way out of extreme poverty. © UNHCR/Jaime Giménez Sánchez de la Blanca

Regional Displacement in the Andes

13-year old Luna Reascos is emblematic of a new generation in Ecuador. Though she was born in Ecuador, her roots trace a story punctuated by forced displacement. Fearful of armed groups and the threat of recruitment that hung over her children, Luna’s grandmother fled Colombia for peace in Ecuador, settling in the port city of Guayaquil. However, faced with entrenched inequalities and rising violence, young second- and third-generation migrants like Luna may be forced to find a future away from Ecuador.

Luna’s is a tragically familiar story throughout the Andes. Made up of Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela, the Andean region has been haunted by violence and instability for decades. Protracted guerrilla wars fuelled by social and ethnic division, exploitative agribusiness and the scourge of the cocaine trade have fuelled one of our planet’s largest and most complex regional displacements. Comparatively devoid of these ills and demonstrating a history of solidarity with refugees, Ecuador has acted as a haven for many of those forcibly displaced.

According to UNHCR, Ecuador received over 76,000 refugees in 2023 making it one of the largest destinations for refugees in the region. The vast majority of these refugees originate from Ecuador’s Andean neighbours. As many as 95 per cent are Colombian, driven by economic uncertainty and internal armed conflict, which continues to disrupt lives in the country despite improvements in recent years. Ecuador also has the fourth largest Venezuelan refugee population in Latin America at over 474,000; a substantial number given the country’s size and its population in comparison to Brazil, Peru, and Colombia, the three leading destinations for Venezuelan refugees. According to the UNHCR, as much as three per cent of Ecuador’s total population in 2023 were migrants or refugees, the majority of whom have settled in the country’s most populous city Guayaquil or in the capital city Quito.

Ecuador’s tolerance towards refugees was demonstrated by the regularization process decreed by the government in 2022. The process aims to register and provide refugees with certification to stay in the country. This legislation supports forcibly displaced people and allows Ecuadorian society to adapt to the demographic changes of migration without the proliferation of typical issues such as poverty and social atomization.

By 29 December 2023, 126,934 visa applications had been made, 87,971 visas had been granted and 72,043 ID cards had been issued through the government’s regularization process. With support from the UNHCR and other NGOs, local organizations have set up spaces and activities for refugees such as football matches in Quito, kayak classes for children in Guayaquil and temporary accommodation for refugees in eight cities supporting around 13,890 people.

‘Since we arrived, I have felt welcomed, as if I were one more Ecuadorian,’ said Juan Carlos Castro, a young Colombian refugee who fled violence with his family in 2005. Juan Carlos is a part of a youth society called ‘Jóvenes Construyendo Futuro’ (Youth Building a Future); a network of 25 young Ecuadorians, Colombians and Venezuelans in San Lorenzo on the Colombian border. ‘It’s like being back home, but happier.’ With community efforts like this, Ecuador has provided an effective blueprint for dealing with the modern challenges of migration. But this harmony faces an increasingly grave challenge.

A deadly power struggle

Cocaine is almost exclusively produced in the coca-growing valleys of Peru, Colombia, and Bolivia, and the international trade of the drug is dominated by drug-trafficking organisations (DTOs) from Colombia and Mexico. But due to its geography, Ecuador plays a vital and often overlooked role in the cocaine trade. Guayaquil is the most common point of export for trans-Atlantic cocaine destined for European cities. This gives enormous strategic importance to the Ecuadorian port city – home to much of the country’s refugee population.

Until 2016, Guayaquil was largely controlled by the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC), the Colombian guerrilla group who benefitted from the cocaine trade for decades. However after the FARC’s peace deal with the Colombian government in 2016, the group demobilized their drug-related efforts and consequently Guayaquil – arguably the most valuable piece of real estate in the global cocaine trade – was up for grabs. A complicated and bloody power struggle ensued, between a concoction of Ecuadorian criminal organisations (primarily Los Lobos and Los Choneros with other fledgling groups), established DTOs from Mexico and criminal enterprises from as far away as Albania. Following the reduction of the FARC’s drug operations in Ecuador, Guayaquil’s strategic importance has been amplified by heightened demand for cocaine in European cities over the last few years.

Deadly violence in Ecuador spiked dramatically over the following eight years. The country’s homicide rate per 100,000 inhabitants, which was 5.8 in 2016, surged to 46.5 by the end of 2023.The power struggle for Guayaquil was the driving force behind this growth, but it was not the only cause. In Ecuador’s 2017 election, Lenín Moreno (2017-2021) replaced Rafael Correa (2007-2017) as president, supplanting socialist policies with a new wave of neoliberalism. Moreno’s policies increased poverty and inequality in the country, fuelling organized crime as well as destabilizing the already precarious livelihoods of refugees.

So far, former businessman Daniel Noboa who became president in November 2023, has done little tackle this issue, with government policies exacerbating inequality and providing impetus for illicit industries. Noboa’s response to organised crime has been to increase military funding, a decision which has drawn criticism from Ecuador’s poorest sectors who do not see the militarization of the country as a solution to social problems arising from neoliberal policies.

Violence reached a peak in early 2024 with coordinated assaults, a high-profile prison break, and the widely-publicized storming of a live television broadcast. Although the State’s response at the start of 2024 was emphatic, with Noboa granting the military sweeping powers to ‘neutralize’ gangs, the long-term outcome of its efforts appears far more ambiguous and risks displacing large numbers of Ecuadorians, as well as refugees already settled in the country.

The central reason for this is Ecuador’s fragmented criminal landscape. Firstly, in-fighting and coalitions prevent one single group from displaying hegemony, inhibiting the state’s efforts to engage effectively witto the gangs, let alone nullify them. Secondly, the country’s importance as an exporter of cocaine has grown alongside other illicit industries such as illegal gold-mining and human trafficking. These interconnected activities together create a diversified criminal economy that provides gangs operating in Ecuador with substantial financial and political leverage. These factors foreshadow a protracted and complicated battle against crime which will almost certainly catch civilians in the crossfire.

Another important factor is the growing spectre of US intervention in Ecuador, which has already attracted comparisons to the defunct Plan Colombia operation which cost close to US$10 billion and devastated swathes of the Colombian countryside in Washington’s ‘war on drugs.’ General Laura Richardson, commander of the US Southern Command, met with Noboa on 22 January to pledge cooperation with Ecuador in the battle against organized crime in the country. Richardson told Primicias, an Ecuadorian news outlet, that the US has agreed to provide Ecuador with a security package worth $93.4 million which includes military equipment and training. With this intervention, Ecuador’s future may become an echo of Colombia’s recent past.

Ecuador in uncharted territory

‘We are all equal, I don’t see the difference’ said Rocio Yupa, the 26-year old Ecuadorian who coordinates Jóvenes Construyendo Futuro. Luna, one of the beneficiaries of the UNHCR’s Community Kayaking initiative in Guayaquil, said ‘I feel good sharing with people from other countries. They are treated just like we treat everyone, as if they were from here.’ With such strong empathy towards refugees amongst Ecuador’s youth, there is reason to be hopeful that Ecuador will remain a welcoming destination for refugees.

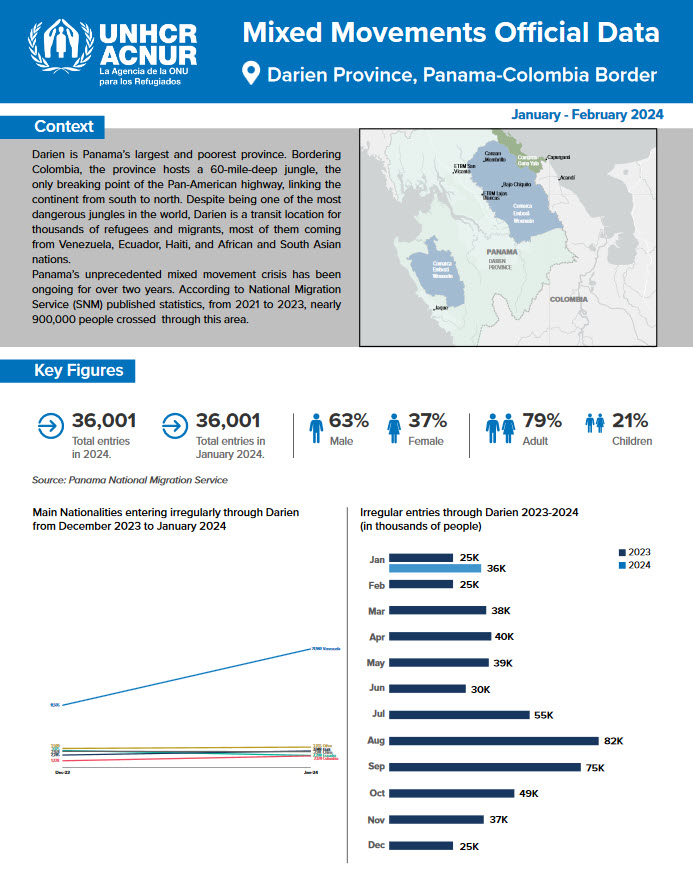

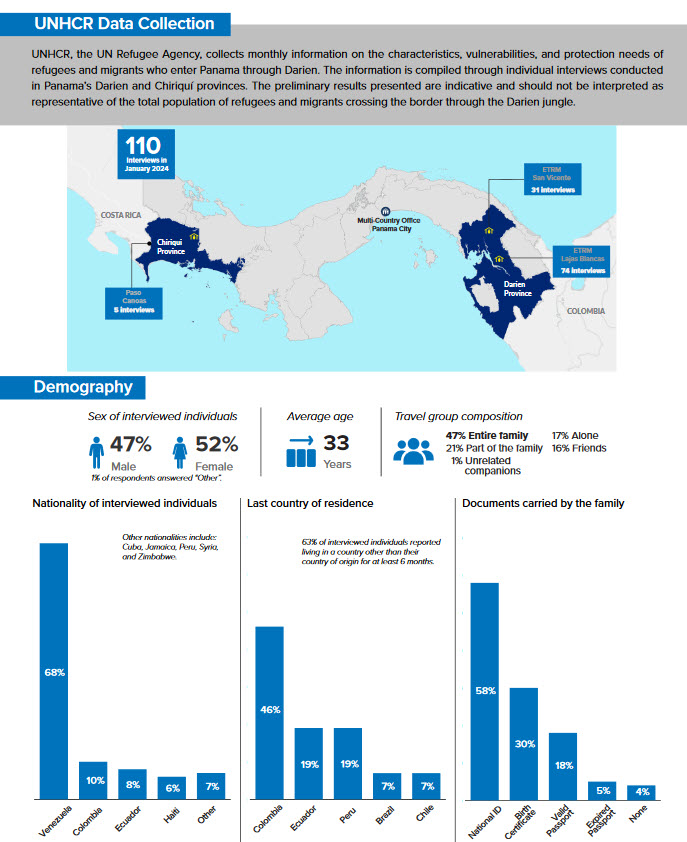

But with increasing gang crime and militarization, it is most likely that forced migration out of Ecuador – which is already high – will continue to rise. In 2023, a record 520,085 people crossed the Darien Gap in pursuit of migration to the United States. This 100-mile stretch of jungle which straddles Panama’s eastern border with Colombia was previously considered impenetrable. According to Panama’s Migration Ministry, Ecuador supplied the second-highest number of people attempting the crossing, with 57,250, behind Venezuela with 328,650. With the prospect of a long and bloody war against gangs combined with deep-rooted neoliberalism, a dose of US interventionism and a diversified criminal economy, Ecuador is heading towards uncharted territory in its history. The waves of violence and instability that have troubled the Andes for decades may have finally flooded Ecuador’s ‘island of peace.’

With one of the largest refugee populations in the region, the effects of this will be profound. On a local level, the livelihoods of refugees who come to Ecuador will become increasingly precarious making them vulnerable to the criminal economy. As a result, young Ecuadorians from refugee backgrounds like Luna and Juan Carlos may face a reality comparable to that which their ancestors fled. More broadly, if it is no longer safe for refugees to migrate to Ecuador then they will be forced into other routes – pushing them towards countries in Latin America’s Southern Cone such as Chile and Argentina or, more dangerously, through the funnel of the Darien Gap into the hands of gangs.

Marley Markham is a journalist and writer from London interested in social memory and race in Latin America.