On 14 December 2022, Peru’s president Dina Boluarte declared a national state of emergency in response to popular protests fomenting across the country in support of her deposed predecessor, Pedro Castillo. Later that day, soldiers opened fire on demonstrators in the Andean province of Ayacucho, killing 7, injuring 52 and reopening the indelible scar that marks Peru’s national memory.

‘They say we aren’t from Peru,’ said one anti-government protestor whose 17-year-old daughter lost her life to the gunfire of soldiers in January 2023. ‘The media call people who protest for their rights “terrorists”’, said another. ‘(They) depict us as ignorant, as people without education and without feelings, even.’

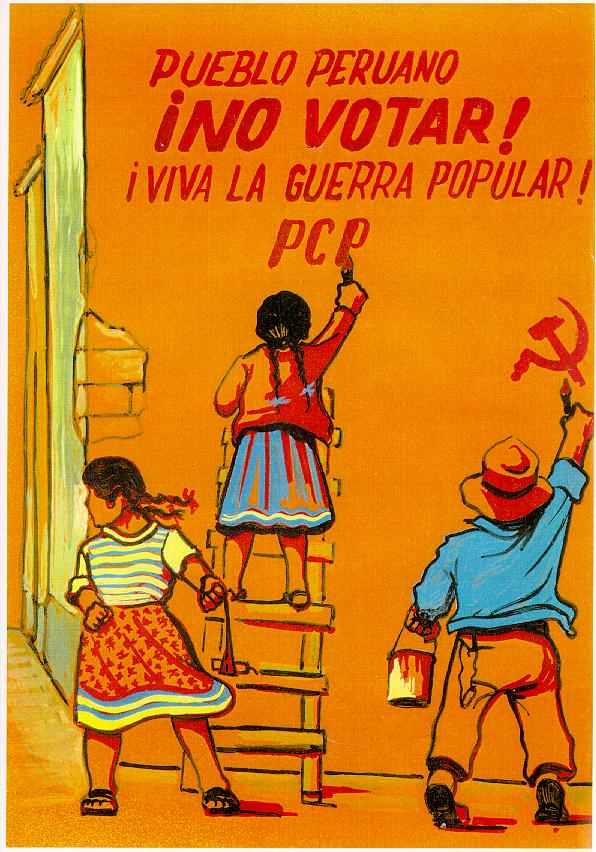

Whilst these accusations may seem excessive, the practise of dehumanizing government critics, progressive politicians and leftist demonstrators as terrucos (terrorists) linked to the Shining Path guerrilla group is not uncommon in Peru. There is even a name for it: terruqueo. Originally coined by the campesino communities of Ayacucho to identify members of Shining Path, the term has since been appropriated by conservative sectors in the twenty-first century as a racially charged insult towards people of indigenous origin.

Perhaps it comes as no surprise then, that the brief presidency of Pedro Castillo – a former school teacher and the son of indigenous campesinos from the rural province of Altiplano – provoked such a visceral flare-up of terruqueo. Whilst Castillo’s campesino identity and Marxist political platform endeared him to vast rural sectors of Peru which had long felt disaffected from Lima, they also attracted fervent criticism from the established political class and media.

During his presidency, the Organization of American States (OAS) identified ‘sectors promoting racism and discrimination, who do not accept the presidency being held by someone outside traditional political circles.’ Castillo was denounced as a terruco by his main opponent, Keiko Fujimori (daughter of former president Alberto Fujimori), and as a donkey – a derogatory symbol for rural poverty in Peru – by her supporters.

As thousands of Castillo supporters took to the streets after his arrest and replacement by vice-president Dina Boluarte in December 2022, the demonization only intensified. Demonstrators were framed as terrucos and delinquents by the press, whilst Boluarte’s national state of emergency – which mobilized the armed forces and restricted various constitutional freedoms – effectively validated this trope and legitimized violence towards protestors.

The following months were punctuated by fatal clashes which, according to Erika Guevara-Rosas, Americas director at Amnesty International, revealed the ‘racist bias towards people protesting in the country, particularly indigenous and campesino people.’ Finding their roots in European colonialism, such discriminatory attitudes are not uncommon in Latin America. However, Peru’s situation derives specifically from a unique watershed moment: the protracted guerrilla war between the military and Shining Path – a Maoist group which sought to topple the state and install a peasant republic through means of protracted violence and devastation. This war caused around 69,000 deaths and ravaged the country from 1980-2000.

From the inception of the war until now, the experiences of indigenous campesinos have been reduced to the oversimplified narrative that they inherently supported the mission of Shining Path. Despite the fact that indigenous rural communities were disproportionately affected by the violence of both Shining Path and the state, with 75 per cent of the conflict’s victims being Quechua- or Aymara-speakers, this harmful caricature of the Andean archetype – or lo andino – has endured until now and is still commonplace.

In order to tackle this misconception, we can draw on the first-hand testimonies of campesino communities in Ayacucho at the beginning of Shining Path’s insurgency which were collected by Peru’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). These help to explain why the group won the support of some communities and not others and will help to challenge the lo andino narrative and encourage understanding.

Senderismo in the Andes

‘I was involved in (Shining Path), honestly without knowing anything about politics, because they said ‘we are fighting for the poor, for the campesino, this war will succeed and then we will take power and live a harmonious life.’’

Former orphan and Shining Path soldier

With economic and political dynamism centred in coastal Lima, Peru’s Andean interior remained at the periphery of the country’s development and, by 1980, Ayacucho was a microcosm of that chronic underdevelopment. At the start of the conflict, Ayacucho was the poorest province in Peru with the highest urban migration rate and a power vacuum left by the effective absence of the state. In addition, with political efforts in the 1980s focused on neoliberal market growth in Lima and other urban areas, there was very little opportunity for Ayacuchans to better their situation.

As a result, many young Ayacuchans felt a strong sense of isolation. The TRC – the most comprehensive report on the conflict undertaken by scholars and humanitarian experts – observed that many young campesinos ‘felt that they were in no-man’s land between two worlds: the traditional Andean world of their parents, which they, at least in part, no longer shared; and the urban-Creole world, which rejected them.’ This collective sentiment of being caught ‘between two worlds’ was common across Ayacucho and restricted how campesinos understood their role in society.

‘Sometimes an Andean man imagines he has power over things,’ native Ayacuchan and former Shining Path child-soldier Lurgio Gavilán Sánchez wrote in his memoir, When Rains Became Floods, ‘But at other times he feels as if he were the most insignificant speck in the universe, unable to do anything.’

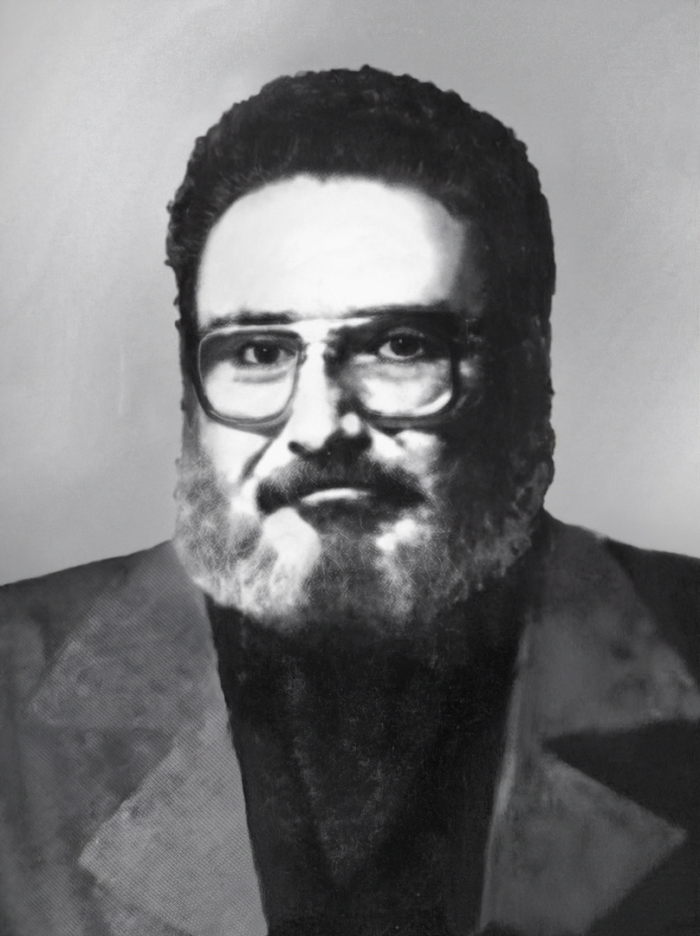

For dozens of young Ayacuchans, Shining Path’s promise of ‘putting a noose around the neck of imperialism’ and creating a ‘new society without substitute, without the exploited or the exploiters’ offered a simplistic and accessible alternative to their destitution. In Ayacucho, the main source of this ideology, known as Senderismo, was the Universidad Nacional San Cristóbal de Huamanga (UNSCH) where the group’s messianic leader Abimael Guzmán was a philosophy professor.

One student said ‘when I joined the university, dialectical materialism (Guzmán’s Maoist ideology) opens your eyes. I understood the process more, that the people had always fought and will fight and that that fight is useful for the transformation.’ In other words, Senderismo posed, at least superficially, an easy solution to the poverty and desolation that Andean campesinos experienced on a daily basis.

‘What has driven me (to join Shining Path) is the oppression, the misery that I have experienced first-hand,’ said another student. ‘The people – the poor – faced the dilemma of what to do: to support the revolution or to support the counterrevolution. Each one decided what path to follow.’

Weapons of the weak

‘There was nothing to do but climb aboard Shining Path’s ark or join the village militias.’

Lurgio Gavilán Sánchez, Former Shining Path child-soldier

Due to the lack of state authority in Andean regions, traditional village militias – known as rondas campesinas – were often responsible for administering justice. These rondas, consisting of local men (ronderos) and overseen by an elder patriarch (patrón), punished transgressions using methods which were often violent such as whipping, shaving and even mutilation.

By 1980 however, such customs were becoming fragmented by high levels of outward migration. The arrival of Shining Path, with its militaristic structure and inflexible understanding of social justice, appealed to campesinos’ sense of law and order.

‘In these parts there used to be people who would steal for the sake of stealing,’ said one campesino from Quispillaccta, Ayacucho. ‘But when the terrorists came, they submitted them to fifty lashes.’

‘Damn! The people with money were sweeping the streets,’ said another campesino from Sancos, Ayacucho. ‘There were no longer any waqras (delinquents), they were punished. Everything was clean and orderly in those days.’ The group’s promise to ‘pull up the poisonous weeds’ and ‘expel these sinister vipers’ through force was not incongruent to Ayacuchan values and initially hinted at positive social change.

Some campesino communities, engaged in longstanding communal disputes, even used Shining Path’s presence as protective shield. In Chuschi for example, the majority of Shining Path’s early targets were from the neighbouring village of Quispillaccta, with whom Chuschians had a long-term feud.

Shining Path’s paternal role in its early stages was designed to garner support amongst the campesino masses andwas not limited to violence. Although they eventually proved unsustainable, collective farming cooperatives were an initiative designed to encourage socialism and egalitarianism in Andean regions.

Regardless of whether they identified with the group’s ideology, many campesinos were willing to tolerate Shining Path’s presence due to the pragmatic benefits which it produced. Of course, this tolerance progressively reduced as the group’s violence escalated. Nonetheless, as distinct from the notion that Ayacuchans inherently sympathized with Shining Path’s mission, we can see that many campesino communities only accepted the group because of the material benefits it produced.

‘Be something, no?’

‘A famous illusion that they created amongst the muchachos (young people) way back in 1981, that by ’85 there would be an independent republic. ‘Wouldn’t you like to be a minister? Wouldn’t you like to be a military leader? Be something, no?’.’

Young campesino from Rumi, Ayacucho

In any society devoid of economic opportunity, an alternative system which may plausibly facilitate social mobility has an irresistible appeal. The promise of becoming a military leader or minister through Shining Path was not only a tangible pathway for upward mobility for Ayacuchans, but a rejection of the status quo and an affirmation of campesino identity. This effect was most pronounced amongst female peasants – or campesinas – who were subject to the dual oppression of chronic underdevelopment on a national level and embedded patriarchal values on a local level.

According to the TRC, at least 40 per cent of Shining Path’s total membership and over 50 per cent of its central committee were female. Instead of being confined to traditional gender roles, female soldiers were involved in violent confrontations, leadership roles and decision-making processes. Whilst Shining Path was by no means a gender-based movement, this dramatic subversion of patriarchy made a lasting impression on campesinas and reveals a profound truth about the relationship between the group and the communities of Ayacucho more broadly:

Despite the façade of millenarianism constructed by Guzmán and propagated by the group’s intellectual inner circle, Shining Path resembled little more than a pragmatic alternative to the difficulties endured by campesino communities in Ayacucho. And even then, sympathies towards the group amongst campesinos never ran very deep and diminished with each fatality suffered. These nuances, which reveal the true lived experiences and motivations of Andean Peruvians, expose the flaws in the simplistic terruqueo narrative.

Healing old wounds

From the campaign-trail to the moment he was inaugurated – sporting the distinct combination of traditional wide-brimmed hat and presidential sash – Pedro Castillo was a lightning rod for bigotry. This extended, often violently, to his supporters. And with her administration so far defined by the 2022 national state of emergency and ongoing security issues, President Boluarte has only perpetuated this.

Now, over two decades on from the end of Peru’s internal war, Shining Path is little more than a peripheral criminal group running drug operations in the country’s coca-growing valleys. The group’s presence is negligible barring episodic spouts of violence. So why is terruqueo still such a prolific – and effective – practise in Peru?

The crux of the matter is that, generally speaking, the demographic of people demonstrating in support of Castillo is similar to that which supported Shining Path. Poor, indigenous, Quechua- and Aymara-speaking peasants from remote rural areas in the Andes. But the true, nuanced motivations of these groups remain obscured. The reality is that, as a consequence of the decades of underdevelopment, discrimination and marginalization to which they have been subject, Andean Peruvians are more likely to sympathise with new intellectual and political movements which promise change. That was true in 1980 – with campesinos obviously unaware of the violence Shining Path would bring – and it remains true in 2023.

And so, the voice of the Andes is far from silent. It is maligned by a harmful narrative which links it to the trauma and bloodshed of the past; but it is far from silent. Untangling the roots of this misconception is essential in redefining our understanding of lo andino, and by so doing moving a step closer to reconciliation.

Main image: a figure wearing the flag and colours of Sendero Luminoso — a common depiction of ‘terruqueo’.

Marley Markham is a journalist and writer from London, interested in social memory and race in Latin America. This article is an adaptation of his dissertation submitted to University College London’s Institute of the Americas.