- The Boa Vista Quilombo in Oriximiná, Pará state, is like many Brazilian quilombola communities. Quilombolas are Afro-Brazilian runaway slave descendants, and point to centuries of inequality and neglect by the government. Quilombos often lack running water, basic sanitation and health services.

- In the 1970s, Mineração Rio do Norte (MRN) annexed much of Boa Vista’s land and established the world’s fourth largest bauxite mine, along with a company town, Porto Trombetas, built on the former quilombo property; MRN also polluted local fisheries and provided mostly badly paid menial jobs to residents.

- Now, the pandemic is exacerbating fundamental governmental and corporate inequalities, say residents. MRN, for example, asked Boa Vista residents to clean a quarantine facility used by new arrivals. The residents refused. Meanwhile, the mine is fully operational, with planes and ships coming and going regularly.

- MRN says it has implemented strong preventative measures against the virus. But residents point out that the company’s hospital has just six intensive care beds; they fear, in keeping with past inequities, these beds would be reserved for MRN employees, leaving infected quilombolas without care.

- This article was first published on Mongabay on 21 May 2020. You can read the original here

BOA VISTA QUILOMBO, Oriximiná municipality, Pará state, Brazil — As the number of Coronavirus infections soars in Brazil, fear is gripping Boa Vista, a small community of quilombolas, Afro-Brazilian descendants of runaway slaves in the Amazon basin.

By May 20, Brazil, with more than 291,000 COVID-19 cases, overtook the United Kingdom (250,000 cases), placing it behind only Russia (308,000) and the United States (1,531,000). Most of the Latin American nation’s Coronavirus infections have been in large urban areas, but the pandemic is rapidly penetrating remote parts of Amazonia, with more than 500 indigenous cases already documented.

Boa Vista has good reason for concern. It is a poor, densely populated village of 155 families, with dirt streets, lacking modern sanitation and health facilities, located a mere half mile from Porto Trombetas, the bustling company town of Mineração Rio do Norte (MRN), the world’s fourth largest bauxite mine.

Porto Trombetas (population 6,500) confirmed its first three COVID-19 cases on 22 April. An MRN employee and two members of his family tested positive for the virus while in isolation after returning from a holiday in Manaus, where the Coronavirus has taken a terrible toll and been called an “utter disaster.”

The close proximity of Porto Trombetas to Boa Vista isn’t the only source of quilombola concern. The municipality of Oriximiná includes one the nation’s most extensive areas of titled quilombo lands, with five formally recognized territories, covering 361,800 hectares (89,400 acres) in the Amazon rainforest. Yet the municipal government’s public health system, which serves all 73,000 people in the district, has only one respirator and no intensive care unit.

“We are very tense. People [from our quilombo] continue to go every day to Porto Trombetas to work,” reports Carlene Printes, a Boa Vista resident. That is happening, even as many ships and planes continue arriving in Porto Trombetas from around the world, potentially carrying the virus, notes Boa Vista Coordinator Amarildo de Jesus. “We are very exposed here,” worries de Jesus.

The anthropologist Lúcia Andrade, executive coordinator of the Comissão Pro-Indio São Paulo, an NGO which has been working in the Trombetas region since the 1990s, agrees. “If COVID arrives [in the quilombos], it’s going to be a disaster,” she said.

An edict from the Brazilian Ministry of Mines and Energy has allowed MRN to continue operating its mine and port, but the company says it is taking prevention measures. It reports that people arriving from outside are isolated for two weeks, and then thoroughly checked before being allowed to leave quarantine.

Questioned about what measures it takes to protect outsourced workers, like those from Boa Vista, MRN said that “to prevent people working [who] can carry out their jobs safely and [who are] duly oriented as to protection measures against COVID-19 … could lead to additional difficulties in earning their living, which would make the situation worse.”

It seemed that the company was not considering furloughing the workers, even the most vulnerable. But two days later, MRN changed its position, saying it was considering providing support for workers thought to be at risk. De Jesus thinks this may be insufficient to protect the Boa Vista outsourced workers. The company had earlier asked them to clean a quarantine facility used by new arrivals and they had refused. “We are thinking of stopping work altogether,” he said. “We have to look after ourselves, as the company is more interested in profit than people.”

Quilombos at risk across Brazil

Boa Vista isn’t alone. Quilombos across Brazil likely share similar Coronavirus fears. “No one points out in the mainstream media that quilombolas are a high-risk group for Coronavirus. We have become invisible in every possible way,” says Gilvânia Maria da Silva, the co-ordinator of CONAQ (Black, Rural, Quilombola Communities).

Da Silva says that the quilombola communities established by runaway slaves in the 18th and 19th centuries mainly in Amazonia and Brazil’s Northeast have never had the backing they need from authorities — social, educational and health assistance has largely been lacking, as has the provision of community land deeds, basic sanitation and transportation infrastructure.

“We have been saying ever since CONAQ was created [in 1996], not just during this pandemic, that we have been abandoned by the State, with a partial or total — and in some cases it is total — absence of public policies. The pandemic just aggravates a situation that was already very bad,” Gilvânia asserts.

According to figures released on 24 April 2020 by the government’s IBGE (the Brazilian Geography and Statistics Institute), there are nearly 6,000 quilombola communities in Brazil. CONAQ reports that many are without basic infrastructure, including running water, making it very hard for people to take basic preventive measures against COVID-19, like washing one’s hands.

Partly because they lack electricity and computers, quilombo residents find it difficult to receive the emergency basic income — R$600 (US$104) per month — that the government is paying workers in the informal economy during the pandemic.

Mistrust of mining company

Boa Vista residents, while feeling abandoned by their government, have little faith in MRN. The company annexed much of their community land in the 1970s; polluted surrounding waterways, destroying the fishery; and contracted a Boa Vista cooperative to carry out many menial tasks, effectively outsourcing this work and reducing the company’s responsibility for those doing these badly paid jobs.

MRN is seeking to overcome the community’s mistrust, particularly acute at the moment, by pointing to other pandemic precautions it is taking, apart from isolation. These include distribution of 1,350 food baskets to quilombola, indigenous and traditional riverine communities, so people don’t have to travel often to Oriximiná. Along with dozens of quilombola and riverine communities, there are three indigenous territories — Kaxuyana-Tunayana, Nhamundá-Mapuera and Trombetas-Mapuera — in the region. It takes 12 hours for the most distant citizens to travel by boat for the nearest medical assistance.

ARQMO (the Association of the Remaining Quilombo Communities in the Municipality of Oriximiná), created in 1989 to support local quilombos, has urged people to stay at home. Even so, says ARQMO Director Claudinete Colé, the flow of people to towns to sell forest products, obtain pension payments, or seek emergency help, is still heavy. “The health situation is precarious. We’re very worried because neither the hospital system in Oriximiná, nor the hospital run by the mining company, has the capacity to deal with this pandemic,” Colé told Mongabay.

In its Porto Trombetas hospital, MRN has just six intensive care beds equipped with respirators (two for children). These are available for quilombolas, if they become sick. However, the community fears that, should a major COVID-19 outbreak occur, those beds would go first to mine employees.

The most recent bulletin issued by the Oriximiná municipal council on 19 May reported 63 confirmed COVID-19 cases in the municipality, with another 13 cases being monitored, and seven deaths. The real figure may be much higher, with research suggesting that throughout Brazil the true number of cases is as much as 14 times higher than official figures suggest.

Under-reporting may be a particularly serious in quilombos, many of which are located in isolated regions. CONAQ has received reliable reports of the virus killing 26 quilombolas, a figure not included in Brazil’s official death rate. CONAQ fears that many more may have died.

CONAQ strongly believes that some of the problems quilombolas continue to face stem from what it calls “institutional racism,” alleging that authorities are not giving the same priority to poor, black communities as to richer, white communities. In a statement, CONAQ wrote: “The inequality in the way Coronavirus is being tackled, already evident in urban areas, will have an overwhelming impact in rural black communities, if the illness expands there with the same speed and mortality.”

José dos Santos, one of the oldest Boa Vista inhabitants, recalls a song by a quilombola composer that laments the long history of prejudice, neglect and abuse suffered by quilombolas. He remembers the lyrics: “Mimi Viana says we are no longer beaten by wooden sticks, no longer whipped, and no longer used as human candlesticks, but slavery hasn’t ended. Instead of putting candles in our hands, they humiliate us.”

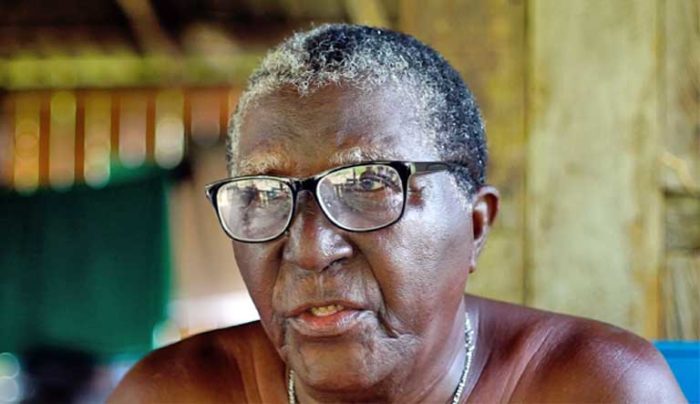

Banner image: The 155 families of Boa Vista, like poor underserved communities around the globe, live in dread of COVID-19 entering their community. Image by Mayangdi Inzaulgarat.