Sara el-Solh speaks to Venezuelan migrant women in Guatemala, some of whom have decided to stay in the country and others who are saving up for the rest of their journey north. All of these women survived the horrifying Darien Jungle crossing from Colombia to Panama looking for better conditions, many with children in tow. They detail their journeys, their incentives, their health conditions, and friends they’ve met along the way.

Guatemala City, Guatemala – ‘What would you do in my position? This was my only way forwards. I can’t waste time wondering if this was the right decision. It was the only decision’. Lizeth is 27 and travelling with her eight-year-old daughter Gabriela. I meet them on La Sexta, a busy pedestrian thoroughfare in Guatemala City centre. Here, Lizeth sells lollipops, surrounded by the preachers, street clowns, goths, drag queens and, more recently, other Venezuelans who make up the beating heart of this turbulent city. Back home in Venezuela she was a primary school teaching assistant. Almost three months ago, following years of hyperinflation and infrastructure collapse which dramatically impacted her quality of life, she left her home and family on Venezuela’s Caribbean coast to begin the long trek north to the United States. Guatemala is her last stop before the extremely dangerous journey through Mexico. Getting here from South America is an odyssey that an estimated 250,000 people embarked on last year, coming from every South American nation as well as Jamaica, Haiti, Bangladesh, Syria and Somalia, among others. An increasing number of these migrants are women, a great many of them accompanied by their children.

Reaching Central America from South America entails hiking through a lawless stretch of land known as the Darien Gap. That journey begins in Necoclí, Colombia, a small coastal town where migrants pay smugglers for an hour-long ferry across the water to Capurganá . From there, they begin their trek through the most dangerous jungle in the world.

The Darien Gap is so named because it is the only break in the Pan-American Highway which stretches from Argentina to Alaska. A sprawling and almost entirely uninhabited expanse, it is filled with inhospitable wildlife such as pit vipers and anacondas, dangerous terrain including several fast-flowing rivers as well as human threats in the form of drug cartels and paramilitary organisations. Until recent years, it was thought to be almost impassable. However, the persistent displacement crisis affecting the whole of Latin America has turned it into an increasingly bustling transit point for many migrants desperate to travel north.

Since early 2022, official records have shown the majority of these migrants to be Venezuelan, many of them women and children. Adriana Gómez Escobar, former programme coordinator at Casa del Migrante in Guatemala City, confirms the upsurge in Venezuelan arrivals was sudden. She says noticeable numbers first began transiting through in June 2021, then in January 2022, Venezuelans were ‘suddenly the majority of people we were seeing. The increase was rapid’.

The journey is recounted with horror by those who have undertaken it. Everyone I spoke to, including children, admitted seeing several dead bodies along the way. David Ismatul, a child psychologist specialising in migration, confirms that witnessing death is a near universal experience for children on this route. Carmen, 24, says she was worried about how the corpses lining their hiking paths would affect her two young children, so she made up stories about them: ‘I knew it would be bad for them to see all that death and know it was other migrants, people like us, that died. So I told them that these were not real bodies, but spirits from the jungle who’d come to protect us. I don’t know if it helped, but I saw so many traumatized children in Darién. I hope mine will be a little less so.’

Lizeth crossed the Darien Gap with her eight-year-old daughter Gabriela in mid-December, 2022. She sums up the experience of crossing the gap simply as ‘hell’. Through tears, she tells me of the time Gabriela was almost swept away in front of her as they crossed the ‘river of death’, one of the most frightening parts of the Darién, only to watch another mother further downstream lose her child to the same current. Gabriela, a bright, smiley girl in a pink jumper and headband, stays quiet while her mother tells the story, only piping up at the end: ‘I saw that too’. She pauses, looking down at the purple doll which survived the last several thousand miles. ‘The little girl died. I think’.

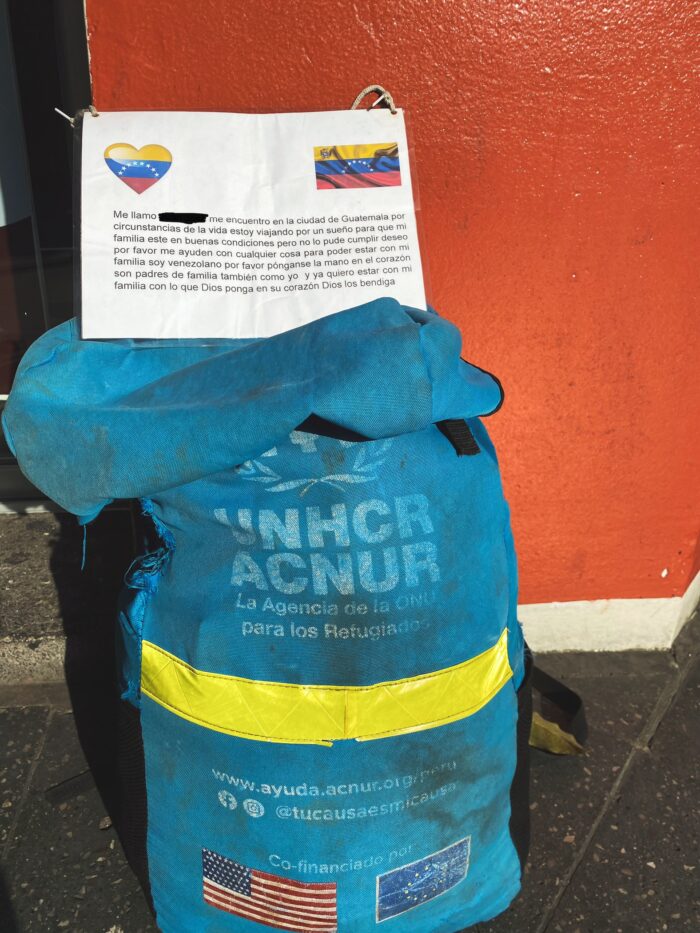

River crossings are one of the most perilous parts of the trek. María, a 21-year old woman travelling with four friends, recalls finding a young child on a riverbank: ‘She looked about two or three years old. She was completely alone. We asked her several times where her parents were and she only replied “the river took my mother”. So we carried her with us for the remaining four days in the jungle and gave her to the UNHCR when we reached Panama’. She shows me grainy videos on her phone of her travel companions wading through knee-deep mud with the girl on their shoulders, singing to her in high, steely voices. Such stories are common among those who survived this brutal trek, and they carry their trauma northwards with them through the seven more countries they must cross to reach the US border.

Most of those making their way north do not want to linger in Central America. Guatemala however is often a necessary stop, both because of the strict border with Mexico (even Guatemalans need a visa to cross it) and because at this point in their itinerary many migrants are running out of money and must delay their threadbare journey in order to gather funds. For many, it is the first time they have really paused for breath since emerging from the jungle, and consequently the first chance they have to inspect the physical and psychological wounds they have suffered along the way.

Lizeth tells me she is keen to push onwards, but like many who have made it this far she is exhausted and in need of rest to plan what she hopes will be the final chapter of this months-long trip. At the end of a weary day selling lollipops with Gabriela, she pools resources with Isabel, a friend she met while crossing the Darién. They bonded quickly and have travelled together ever since, helping to look after each other’s children and raise each other’s spirits on the road. Having earned enough for that night’s room, they make their way several blocks southwest of the centre, past brothels, hotdog stands and tiendas selling fresh tortillas, crossing at a traffic light where two youngsters juggle fire in front of waiting cars, to reach a strip of cheap hotels where they can finally put down their bags for the night.

All of the women I spoke to in Guatemala City had at least one injury or illness directly related to their migratory journey. For some, their travels worsened existing complaints while others became ill or injured along the way. All described diarrhoea and gastrointestinal upsets caused by the necessity of drinking river water in the Darién, and several women hypothesised this was due to the numerous bodies swept away by tumbling currents now decomposing in the rivers they drank from.

Not having any water, however, can be even more deadly. Mariana, 25, reports witnessing another woman attempt to rehydrate her baby with her own saliva because they’d run out of water. ‘She was spitting into her baby’s mouth because we didn’t have any water. Nothing’. Diarrhoea and severe dehydration are particularly dangerous for young children and Carmen recalls that one of her sons began fitting on their last day in the jungle. Tears well up in her eyes as she tells me she had to carry him through the last few miles of rough terrain, ignoring the pain in her own swollen, blistered feet.

Foot injuries – some severe – are another story frequently told. Most people undertaking this journey do not have spare cash for protective footwear and even if they did, no shoe can shield you from over 12 hours a day of near-vertical climbs through thick mud, river crossings, snakes and scorpions. Those who are lucky enough to escape injury often develop infections resulting from walking days on end with wet feet. This tortuous jungle trek ends in San Vicente migrant centre, where a meagre medical facility run by MSF sometimes sees hundreds of foot injuries per week.

Pregnancy further complicates the route for some. Daniela, 21, is travelling with her husband and six-month-old son, Carlos. She tells me her pregnancy was difficult as she suffered from preeclampsia (a blood pressure disorder that can occur during pregnancy) which resulted in an emergency induction at seven months. The couple were already on the road in Colombia at the time, and Daniela blames the stress of leaving her family behind for worsening her condition. ‘I was so lonely, and every day thinking of my family at home. On the road, we never know where we’re going to sleep the next day, or if we’ll eat. Of course this stress affects me. Of course it affects my baby’. Carlos spent the first two months of his life in a specialised neonatal unit in Colombia while his parents struggled to make ends meet and planned the rest of their itinerary. As soon as he left the unit, the family made their way north into Central America.

As well as pregnancy, postpartum is a risk on this journey. Susy, 29, developed haemorrhoids during her second pregnancy and says her trip, with the long hours on her feet carrying a heavy backpack, has made them worse than ever before. She tells me that, although she’s in a lot of pain and public hospitals are free in Guatemala, she’s afraid to seek medical care because in every encounter with the Guatemalan state she has been subject to violence or discrimination. ‘When we crossed the border [from Honduras] the border guards were organised with the trocheros [people smugglers] to threaten and extort us. Now in Guatemala City the police harass us all day. We’re not doing anything wrong but they treat us like criminals.’ The same is true of Tania, 24, who suffered a fourth-degree tear during childbirth just six weeks before starting her journey. She confirms this was sutured but now describes worrying symptoms of an obstetric fistula (a hole between the vagina and the bladder or rectum). She says she knows she needs to see a doctor but is afraid to seek care.

For all of these women, ahead lies Mexico. A huge and often hostile stretch of territory larger and more dangerous than the Central American countries combined; the journey through it is often discussed in hushed tones. Three of those I spoke to had already been deported from Mexico. Mexican authorities do not deport migrants to their country of origin, instead simply casting them back over the border to Guatemala, further straining a local infrastructure already stretched to breaking point. This leg of the journey is also particularly dangerous for women and girls, in large part due to the threat of kidnap and sexual violence from cartels, some of which have recently been increasingly specialising in extorting migrants. All of the women I spoke to were sanguine about the risks, seeing them as a necessary evil in their struggle to reach the USA.

Lizeth’s chief concern was Gabriela. She confided that she was planning on cutting her hair short and dressing her as a boy while they crossed Mexico. ‘I talked to her a lot about it, to prepare her mentally. I explained it’s safer this way. It’s sad I have to tell her these things at her age. But I’ll do anything to keep her safe, she’s the most important person in the world to me’.

For some, however, the risks are too great and seeing them in such close proximity while in Guatemala is too daunting. A small but growing minority of migrants are deciding to stay and seek asylum. Some have experienced the horrors of Mexico first-hand and conclude they cannot attempt it again, while others are disquieted by stories they hear from family and friends.

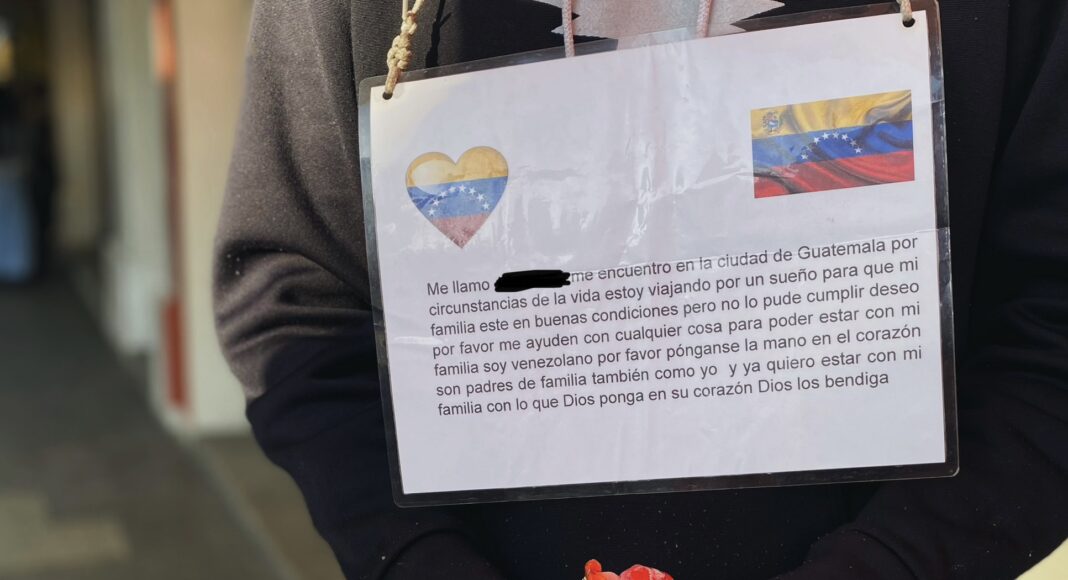

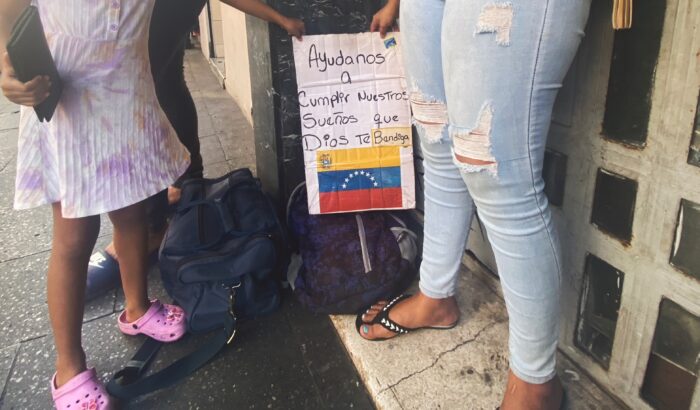

Mariana, along with her husband and seven-year-old daughter, has resolved to settle here and attempt to make a life: ‘it’s not what we wanted when we set out, but we’re happy for now’. She says they made this compromise based on reports from her sister about the dangers ahead in Mexico and from friends about the challenges of living in the USA. ‘Some people say Mexico is even worse than the [Darién] jungle. There are so many people trying to rob or hurt you there. I know many people who’ve experienced this’. She looks briefly at her daughter playing beside me as she tells me of friends whose children have experienced racist bullying in the USA. ‘My friends told me their children were hit hard by this. It’s very difficult for children to suffer discrimination’. Deterred by these fears but determined, the family sets out every morning for La Sexta with bags of sweets to sell and a handmade cardboard sign with the red-yellow-blue Venezuelan flag and large letters that read ‘please help us accomplish our dreams. God bless you.’

Sara el-Solh is a medical anthropologist, medical student, and organizer based in Scotland via Lebanon and Guatemala. She researches and organizes around health justice, with a focus on migration and climate change.