This article was published by David Hill on his Substack account on 23 November. You can subscribe to his posts here. LAB is grateful for his permission to reproduce it. The main image was added by LAB.

Main Image: Fazenda Atlantica in Acre state, western Brazil. Photo: Diego Gurgel

No one should need any more good reasons to care about or want to protect the Amazon basin, home to the world’s largest and most biodiverse rainforest. After all, there are already so many: the forest’s own inherent worth and value, for example, or the 100s of Indigenous peoples who live there and the millions of others who do likewise. Then there is all the spectacular wildlife and other critters who make it their homes too, and the pharmacological riches of so many trees and plants still waiting to be better understood. That is to say nothing of the role that the region plays as a kind of giant “sink” by absorbing carbon dioxide – something we hear about more and more these days, given the global climate crises.

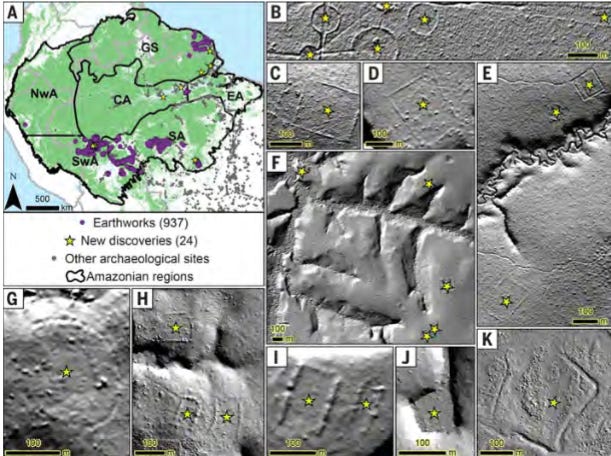

But now there is another reason: 1000s and 1000s of archaeological sites dating from prior to the arrival of the first Europeans in the 15th century. According to an article last month in the journal Science, titled “More than 10,000 pre-Columbian earthworks are still hidden throughout Amazonia”, “between 10,272 and 23,648 sites remain to be discovered.” This research is described as the “work of hundreds of different scientists and research institutions in the Amazon over the past 80 years”, with the lead author named as Vinicius Peripato, from Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research.

However, these “earthworks” – “ring ditches, geoglyphs, ponds, and wells”, believed to have performed a variety of “social, ceremonial, and defensive functions” – are increasingly at risk as more and more of the Amazon’s forests are razed.

The main driver? Agribusiness.

“Ironically, modern-day deforestation is removing the very evidence of pre-Columbian land-use strategies that were able to transform the landscape without causing large-scale deforestation,” Peripato et al write. “Today, Amazonia is experiencing expansion of agriculture and cattle ranching, especially where earthworks are concentrated in the southern and southwestern regions, risking the destruction of earthworks and fracturing and hampering the identification of pre-Columbian occupation sites that provide direct evidence of ancient Indigenous territories.”

In other words, razing forests across the Amazon does not just devastate Indigenous peoples’ territories, homes, sources of food and livelihood, culture and identity, as has become increasingly well-known in recent decades, but erases evidence potentially proving their historic connection to those very same areas. And that evidence could be vitally important given ongoing land rights struggles.

“These archaeological legacies can play a role in present-day debates around Indigenous territorial rights,” Peripato et al continue. “They serve as tangible proof of an ancestor’s occupation, way of life, and their relationship with the forest. Today, Indigenous peoples struggle to recognize their right to land originally inhabited by their ancestors, along with the protection of their territories, languages, cultures, and heritages.”

When I asked Peripato how his research could be used to push for land rights in practice, he said that the titling process, in Brazil at least, is already clear.

“During the first stage of the current Indigenous Land demarcation processes in Brazil, an anthropologist leads a study that includes “research on the ancestral occupation of Indigenous land according to the memory of the ethnic group involved”,” Peripato says. “Therefore, the existence of scientific discovery and research is already used as a basis to prove the ancestral Indigenous occupation within a territory and to proceed with the other stages of the demarcation processes.”

Peripato also emphasised the significance of this research in the context of the so-called “Marco Temporal” legal argument that has generated so much outrage in Brazil in recent years because it proposes that new indigenous territories can only be demarcated if the Indigenous people living there can prove they have done so since before 5 October 1988, the day the country’s current Constitution was enacted. In September Brazil’s Supreme Court declared “Marco Temporal” “unconstitutional”, but a bill including it was approved by the Senate the same month before being vetoed by President Lula de Silva.

“Since the colonization of Brazil, Indigenous societies have faced various types of pressure and violence, forcing these peoples to move across the territory, including having their lands invaded,” Peripato tells me. “If science provides evidence that Indigenous peoples inhabited these areas, it opens space for a debate about the real right to them. About 40 years ago, it was believed that the Amazonian forest was pristine. Today, there is increasing evidence of the relationship between ancient Indigenous peoples and the Amazon. So, knowing that studies of Indigenous Lands consider this ancestry, it would be possible to link our findings with new demarcation requests, as well as foster a debate on the real right to the land in terms of ancestry, rather than being tied to 1988.”

Michael Heckenburger, a US archaeologist who has worked for decades with the Indigenous Kuikuro people in Brazil’s upper River Xingu region, describes Peripato et al’s point about the “earthworks” contributing to land rights struggles as “extremely important.”

“Until recently – and largely due to deforestation, roads, urbanism and other development – archaeological evidence was hidden under forest canopy,” he says. “They do provide tangible proof of ancestral occupations, which reveals their extent and complexity and is important for territorial rights.”

Heckenburger also believes that the findings published in Science – together with the research technology used, dubbed “LiDAR” – “have obvious and important implications” for the “Marco Temporal” argument too.

“This is one area the LiDAR is really groundbreaking in providing the means to determine the distribution of archaeological/Indigenous heritage sites,” he says. “The LiDAR identification of earthworks is all the more relevant, since these are late, the 500 years or so before European conquest, and they are in some instances directly ancestral to Indigenous peoples living in these areas. So, not only do they demonstrate an Indigenous presence in the past, in general terms, but can be linked to specific descendant populations, such as in the Xingu, where I work, and where the authors show LiDAR on what appears to be one of the Kuikoro’s sacred ancestral sites. The LiDAR provides information hard to obtain in forested areas and directly relevant to the question of overall Indigenous occupation of Amazonia and specific regional cultural trajectories, and is therefore significant to questions of Indigenous land tenure and use.”

However, Heckenburger believes that, to best support indigenous land rights and territorial integrity, Indigenous peoples themselves must be involved with this kind of research, which he says “is not the case here.”

“Research needs to be done in consultation with Indigenous peoples, particularly in areas recognised or viewed by them as their traditional territories,” he says. “The first case [Peripato et al] show is a flyover of the Territorio Indigena do Xingu (TIX), including one of their principle sacred sites, but it did not include consultation with Indigenous communities in the TIX or even with researchers and NGOs working closely with them. The mounds identified were often used for ritual purposes, at least part-time, which should involve Indigenous groups. Beyond helping to rectify knowledge sovereignty and self-determination issues associated with such top-down approaches, putting these technologies and results in the hands of Indigenous people will have the most impact of defending territory.”

When I asked Peripato about including Indigenous peoples themselves in this sort of research, he said the “central idea was to find the earthworks” and that it turned into a “5-year long office-based job”, but acknowledges that must be the case in the future.

“I believe that the Indigenous peoples’s involvement begins now, using our research as a tool for discussion and verification,” he says. “For the future, undoubtedly, their participation in prospecting, validation, protection, and policies related to these findings is essential, both for their own representation and for their rights.”