Interviewed by CLACS Newton International fellow Gabriel Bayarri, Argentine author Uki Goñi provides insight into Argentina’s intricate history. As a witness to the erasure of truth and the moral decline leading to the 1976 military coup, Goñi draws alarming parallels between that period and the present political discourse which is marked by extreme views and abusive behaviour.

GB: Your knowledge about the figure of Eichmann and the reflections elicited by Hannah Arendt’s report Eichmann in Jerusalem make me wonder if you see any correlation between the phenomenon of presidential candidate Javier Milei and a process of banalization of violence in the Argentine context. If so, could you elaborate on the artifacts through which such violence is normalized?

UG: Many Argentines hold the view that their country is largely untouched by violent conflict. However, in reality, Argentina has a history of mind-boggling bloodshed.

As early as 1865, Argentina led what was perhaps the most destructive war in Latin American history when President Bartolomé Mitre, as the supreme commander of the allied forces of Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay, decimated Paraguay. According to some estimates, Paraguay lost 90 per cent of its male population and up to 70 per cent of its total population.

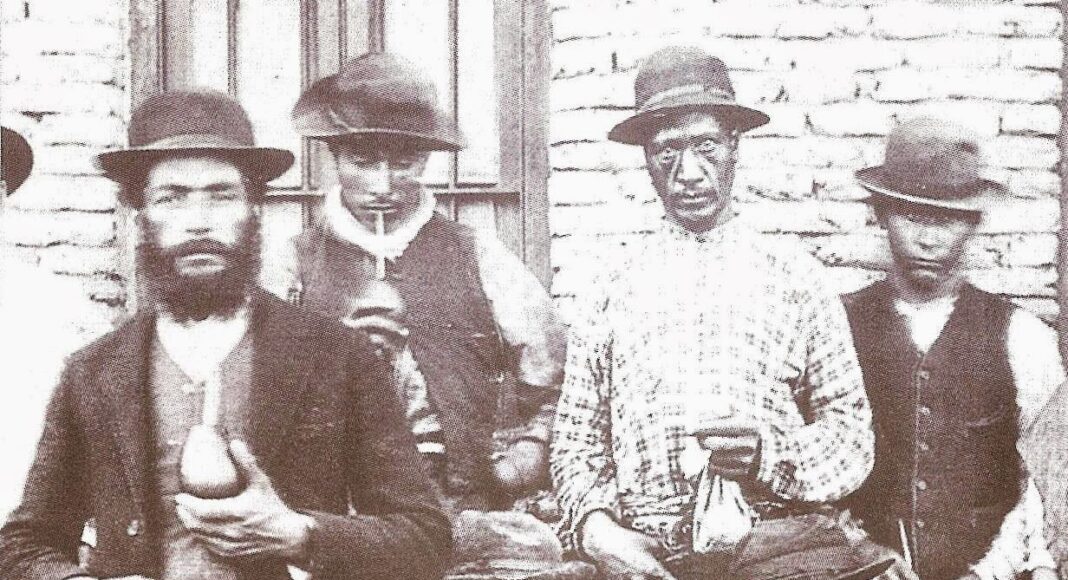

Five years later, this Paraguayan genocide was followed by the massive ethnic cleansing of the indigenous peoples of Pampa and Patagonia by Argentina’s white rulers. At least half of the region’s 60,000 indigenous inhabitants are estimated to have been killed in a ‘Desert Campaign’ that ended in 1888, with their seized lands making Argentina an agricultural powerhouse.

This history is coupled with Argentina’s involvement in the Atlantic slave trade, both pre-colonially and post-colonially. All of this occurred against a backdrop of continual fratricidal wars among Argentina’s 19th-century generals, warlords, and landlords.

Given this long history of genocidal conflict and official concealment of these crimes, it’s not surprising that after World War II, during which Argentina claimed neutrality, there was minimal negative response to the arrival of Nazi war criminals.

This lack of response might be due to the erosion of fundamental norms of peaceful coexistence over time. The presence of these Nazis merely reaffirmed the habit of coexisting with evil. Imagine having a German SS member living on your block, possibly involved in the Holocaust, yet greeted with a smile at the grocery store. What psychological impact would this have?

This erosion of ethical boundaries created a moral vacuum by the 1970s, allowing the genocidal crimes of the dictatorship to occur without significant opposition from the church, political parties, or the press. Instead, these social actors denied or dismissed the crimes, further fuelling the national paranoia of an international conspiracy against Argentina.

This cycle of denial was finally disrupted during the 1985 trial of the military juntas. The televised testimonies of death camp survivors forced Argentina to confront its capacity for mass violence. Despite a fragile consensus that emerged after these trials, recent developments suggest the breaking of this consensus, with the rise of right-wing politicians like Javier Milei, who may become influential in the upcoming October presidential elections.

GB: Building on the sociological aspect of violence, I wanted to ask about your recent experience of being represented in images such as memes. Could you share your thoughts on how you perceive these images, both theoretically and personally, considering their potential to spread fake news and cause harm?

UG: Another prevailing myth in Argentina is that of being an off-continent European nation, owing to the significant influx of Spanish and Italian immigrants during the 19th and 20th centuries. It wasn’t until 2021 that I had the opportunity to write about Argentina’s need to confront its history of indigenous genocide and involvement in the Atlantic slave trade, based on the work of Afro-Argentine scholars and activists, along with the insightful book Hidden in Plain Sight by Erika Edwards.

This led to questions raised by Black Americans about the erasure of Black history in Argentina, amplified through platforms like Twitter. A Black YouTuber even flew to Argentina to create content on the subject.

The debate intensified during the previous year’s World Cup when my article in the [8 February 2021] New York Review of Books highlighted the whiteness of Argentina’s national team as an example of how Black identity has been erased in favour of the ‘Argentina is part of Europe’ narrative.

Consequently, I faced a targeted hate campaign on social media, inundated with menacing posts and messages daily, ranging from ‘Uki Goñi was found dead’ to ‘Fatwa against this villain.’

Strangely, anti-Semitic memes emerged, perhaps because I had written about Nazi escape to Argentina, along with threats and slurs. This campaign aimed to brand me as Jewish, anti-Argentine, a spy, gay, or physically unattractive.

What incensed these attackers was my assertion that racism persists in Argentina. They argued, ‘There is no racism in Argentina because there are no Blacks,’ disregarding the existence of a proud Afro-Argentine community and mixed-race individuals.

The intensity of this anger reaffirmed to me the deep-seated nature of racism in Argentina, especially the thousands of posts labelling me as Jewish. It was the first time that I reported some of the worst threats to a cybercrime-specialized prosecutor’s office. A plea agreement has now been reached that mandates attending courses on civic values, including at Argentina’s Holocaust Museum, and refraining from any communication about me.

Despite clarifying that I am not Jewish, the charge of anti-Semitism persists.

GB: Considering your works ‘Silence is health – how totalitarianism arives‘ and ‘The Hidden History of Black Argentina’, I’d like to delve into a comparative perspective, leveraging your understanding of the US. Could you share your insights on the expression of racism in Argentina and the United States, focusing on the formation of identity-based movements?

The US has grappled with the legacy of historical apartheid, fuelling strong identity movements based on race. Contrastingly, some Latin American countries, emphasizing false racial harmony, have struggled to articulate similar identity-based movements. I’m eager to hear your thoughts on this phenomenon within a comparative framework.

UG: Growing up in the US, I was acutely aware of the racism faced by Black individuals. The school I attended, Annunciation School in Washington DC, was exclusively white during the 1960s. My interactions with black kids in the neighbourhood were limited to conversations during my ‘Patrol Boy’ duty.

The stark whiteness of Annunciation School stood in stark contrast to my previous educational experience in Mexico, a country that celebrates its mestizo heritage. This contrast highlighted that such diversity would be unlikely at a US school like Annunciation.

Argentinians argue that their society lacks racism against mestizos, particularly those assimilated with purchasing power. Yet, racism persists against individuals with obvious Black or indigenous heritage, especially if they are marginalized.

The use of the Spanish word ‘negro’ in Argentina is cited as non-racist, often used affectionately. However, it becomes discriminatory when applied to someone outside their immediate circle. The absence of ‘No Blacks’ signs in public transport does not negate a history of racism or its contemporary existence. Afro-Argentine and ‘brown’ activists are increasingly vocal about their underrepresentation in various sectors. Writing about racism in Argentina, as I did, can provoke death threats.

Uki Goñi is best known for his book The Real Odessa: How Nazi War Criminals Escaped Europe, Granta Books, London, 2022. He has written a series of stories on human rights and the environment for the Guardian, op-eds for the New York Times and essays on authoritarianism and racism for the New York Review of Books. Born in the US to an Argentine family, he was raised in Dublin where he lived until the age of 21. He resides in Buenos Aires.

Gabriel Bayarri Toscano is a Newton International Fellow at the Centre for Latin American & Caribbean Studies (CLACS) at the Institute of Languages, Cultures and Societies. His current project is: ‘Discourse Polarisation: The Memetic Violence of the Latin American Right-Wing Populisms’.

Main Image: Afro-Argentine gauchos, 1895. Photo: Argentine Ministry of Culture