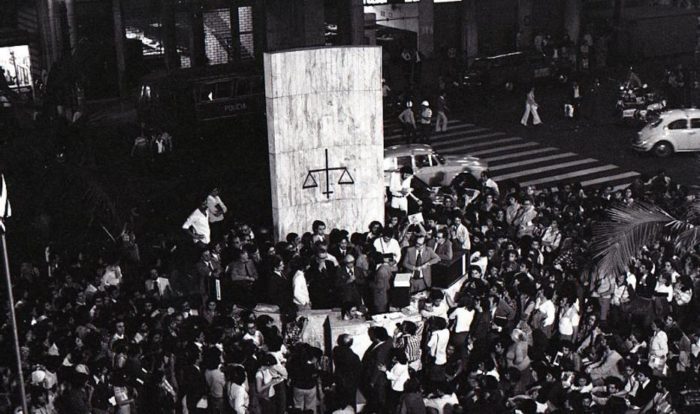

São Paulo, 12 August 2022. On 11 August, at over 70 law faculties up and down Brazil, thousands took part in pro-democracy demonstrations. The high point was the reading of the famous Letter to Brazilians, or Carta pela Democracia, written by São Paulo law professor Goffredo da Silva Telles Junior and other lawyers in 1977, and read aloud in the law school of the University of São Paulo, located in the Largo do São Francisco in the centre of the city.

Then, 45 years ago, General Geisel had just closed down Congress and introduced a series of anti-democratic reforms, including what became known as ‘bionic’ senators, nominated by the government instead of being elected. The 1977 Letter denounced the dictatorship and called for democracy.

Carta pela Democracia 2022. See the Reading of the complete document at the Faculty of Law of the University of São Paulo. Video: UOL, 11 August 2022

Now in 2022, the new Carta, signed by over one million people in the two weeks since it was launched, aims to support democracy and the rule of law and to denounce the threats against it, coming principally from the president.

The letter did not mention Bolsonaro by name, because the demonstrations were deliberately non-partisan, and the manifesto, or Carta, was signed by every presidential candidate except Bolsonaro.

Participants in the 1977 action were fearful of being arrested and had prepared escape routes through the labyrinthine corridors of the old building. Today, what is feared is an attempt by President Bolsonaro to overturn the results of the elections, should he lose to Lula.

No going back

For those, like me, who witnessed the 1977 movement and the reading of the original Letter, today’s events were like a flashback to those times, as speaker after speaker defended democracy, and denounced attempts to turn the clock back. One compared democracy with oxygen saying we only feel the need for it when we don’t have it.

The 1977 Carta was signed by a handful of jurists and lawyers. The 2022 version has been signed, not only by jurists and lawyers, but also by businessmen, doctors and journalists, students and trade unionists, taxi drivers, and at least 8,000 police officers.

The speakers also represented a much more diverse Brazil. Many of them were women, including black women. The once all male, all white law faculties now count many black men and women among their students and faculty members. Twenty elderly survivors who signed the 1977 Letter mingled with young afro-Brazilian students. Bankers and business leaders sat side by side with trade unionists and community leaders.

Speakers called not just for democracy but for racial democracy. Student leader Manuela Morais, said ‘we don’t want the democracy of hunger and massacres, the democracy of the rich, we want the democracy of diversity, of the workers – real democracy.’

The Brazilian Trade Unions CUT, Força Sindical, UGT, NCST, CSB, Pública and Intersindical Central da Classe Trabalhadora resolve to support the manifesto for democracy and justice. Video: Cortes TV, 29 July 2022

Speaking for the Black Rights Coalition, Beatriz Santos said there is no democracy without an end to racism. The leader of the General Trades Union, Francisco Canindé Pegado, compared the democracy movement to a battleship, maybe thinking of one called Potemkin.

He said he represented 60 million workers, and that ‘we cannot accept that the president of the republic does not respect the constitution that he swore to respect.’

Everyone stressed that this was a movement of civilian society to impede the return of a dictatorship. ‘Society, united, will never be defeated’, they chanted.

Worth ‘less than toilet paper’

The final straw which led to the sudden appearance of the pro-democracy movement after almost four years of Bolsonaro’s government, was the president’s July meeting with ambassadors when he trashed Brazil’s widely respected electoral system, suggesting it was open to fraud and insinuating that he would only respect the result if he won. Greeted with incredulity, that meeting sparked the decision by Celso Campilongo, director of USP’s law faculty, to reproduce the 1977 letter, and invite others to sign it.

Bolsonaro criticises the country’s electoral system during a meeting with ambassadors. Video: Record News, 18 July 2022

This led to the production of several other manifestos, including one signed by São Paulo’s powerful, and traditionally conservative, federations of industry (FIESP), and by banks (FEBRABAN). This manifesto also was read out at the law faculty ceremony.

This was an important signal that the majority of Brazil’s economic elite will not support a coup attempt, because in today’s world, coups are bad for business. Ex-president of the Central Bank, Arminio Fraga, who also spoke at the ceremony, noted that the most prosperous societies are all democracies. The US government also took pains to make clear, after Bolsonaro’s fiasco with the ambassadors, that it believes in the integrity of Brazil’s electoral system and is not going to support a coup.

President Bolsonaro again described the manifesto read this morning (11 August) as a ‘cartinha’, or note, resumed his attacks on ex-president Lula, and the other signatories of the Carta, stating that in legal terms it was ‘worth less than toilet paper’. Video: Morning Show, 12 August 2022.

Bolsonaro’s pathetic response to the demonstrations was to announce a reduction in the price of diesel fuel as an important action to benefit the Brazilian people. Later he said the Letter to Brazilians, signed by over a million people, had no legal effect and ‘was worth less than toilet paper.’

Nostalgia for dictatorship

Once again, I was reminded of the dictatorship, when a petition signed by over a million people, laboriously collected by the grassroots Cost of Living movement to protest at high inflation, was rejected at the Presidential palace because some of the signatures were written in the same hand, where friends or relatives signed for illiterates.

Nostalgic for the dictatorship with its repression, torture and censorship, Bolsonaro seems to be successfully reproducing some of its other effects.

What remains still an enigma is the reaction of the armed forces if Bolsonaro loses the election, now less than two months away, and claims fraud, following the example of his idol, Donald Trump. The Minister of Defence, General Paulo Sergio Nogueira, continues to harass the Supreme Electoral Board (TSE) with unreasonable and irregular requests for information. Yet this is the same general who just a few days ago signed up to the OAS commitment to democracy at a meeting of regional Defence ministers. The next big test of Brazil’s democracy will come on 7 September, when Bolsonaro seems bent on turning what should be a patriotic ceremony to celebrate 200 years of independence from Portugal into a political event for his re-election campaign, turning the traditional military parade into a rally in his support.