On Sunday 30 October 2022, thousands of Brazilians living in the UK voted for the future president of their country.

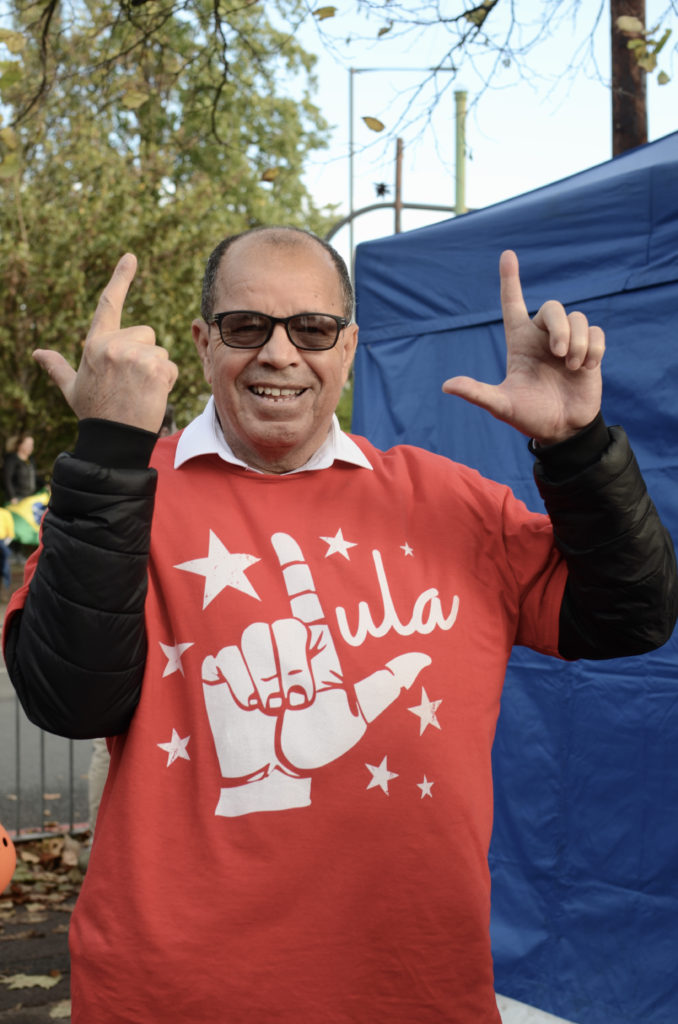

Outside a polling station at Hammersmith and Fulham College in west London, the crowd was divided. Separated by a metal railing and the colours of their clothes, they made up two sides of a polarized diaspora. Politically segregated, yet nationally united, they are the embodiment of contemporary Brazil.

One day later, on the morning of Monday 31 October, they finally have their answer.

Given that neither the incumbent Jair Bolsonaro, or his opponent Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, received more than 50 per cent of the vote back in the first round, on 2 October, last night’s runoff went right down to the wire.

Lula’s victory is a great result for many, not least the majority of indigenous communities and Black Brazilians who have faced increased discrimination under Bolsonaro’s regime. That being said, with only 50.9 per cent of the votes to Bolsonaro’s 49.2 per cent, it’s an uphill battle ahead for the left-wing leader.

The charges of corruption brought against Lula and his criminal conviction (quashed in March 2021) were the main reason for one Bolsonaro supporter’s distrust. Sandro Souza, originally from Espírito Santo, was chatting comfortably with a Lula supporter in a red beret, when I approached him for an interview. Bolsonaro ‘is the best option we have,’ he explained before posing for a picture, proudly puffing his chest to display his ‘Bolsonaro 2022’ t-shirt.

On the other side of the coin, Lula’s supporters feel the same way about him. And they’re generally keen to protect him from criticisms of his past. Operation Car Wash, the investigation which indirectly sent him to prison back in 2018, was nothing more than a political witch-hunt, according to most of the supporters I asked.

It is not surprising, given all the information and disinformation in circulation, that this election sparked acrimonious dispute. This was clearly demonstrated by another protestor, Erica, who gave an impassioned answer to my question – why are you here today?

‘I’m here because I want to save my country, literally, from this man who is destroying Brazil. Who is destroying the Amazon, who is destroying the Black people, who is destroying the Indigenous people, and who just doesn’t care.’

According to a 2019 report published by the Missionary Council for Indigenous Peoples (CIMI), cases of ‘possessory invasions, illegal exploitation of resources, and damage to property’ in the Amazon and the Cerrado more than doubled in the first year of Bolsonaro’s presidency. But there is hope, as 181 Indigenous candidates took part in Brazil’s 2 October general election (held at the same time as the presidential first round) – a 36 per cent increase in four years. Amongst the five elected candidates were two prominent indigenous activists – Sônia Guajajara and Célia Xakriabá – as federal deputies for the Bancada do Cocar (the Feathered Headdress Caucus).

As for Black Brazilians, representation in Bolsonaro’s congress fell far short. Despite making up 56 per cent of the population, they counted for only 18 per cent of the country’s congress under the last regime. Now they are fighting to be heard, from all points on the political spectrum.

This election has been immensely personal, in more ways than one. As Boneco de Sousa, a Brazilian from Brighton told me; ‘as a result of having Bolsonaro’s government in power, I lost my parents to Covid.’

President Bolsonaro’s handling of the COVID19 pandemic has been widely criticized by organizations including Human Rights Watch and UNHCR. Describing the virus itself as ‘a bit of a cold’, the maverick president also made a series of false claims about the vaccine, including that it made people more susceptible to contracting AIDS.

Fake-news led Brazil into a self-perpetuating cycle of misinformation and deceit. And that is where we are today, two years later, at the end of a polarizing presidential race between a ‘cannibal’ and a ‘Satanist’, according to some ‘news’ sources.

But for Renata, another voter I met, ‘[Bolsonaro] has tidied up our country, cleaned up all the rats that lived in parliament… and put the economy up’. There is also ‘not one single person without money in Brazil,’ she told me in reference to his government’s welfare payment plan, which distributes 600 reais per month to the poorest households in Brazil. You can hear the passion in her voice, the certainty of her hero’s good intentions.

Yet such relief is temporary, according to the World Bank; whilst poverty levels declined from 26.2 per cent in 2019 to 18.7 per cent in 2020, that figure rose to 28.4 per cent in 2021.

Lula’s victory last night sent a wave of relief through the households of many Brazilians around the world; but disappointment will inspire anger in the hearts and minds of his adversaries.

What’s more, this polarization does not begin or end with Bolsonaro and Lula. They are symptoms of something much greater than themselves – an ideological battle between nationalism and socialism sparked by disillusionment with the status quo.

In fact, if the razor-thin margin by which Lula won is anything to go by, then things are just getting started.

Main image composite from photos by author.

Ana Maria Monjardino is a Portuguese-Colombian journalist from London, with an interest in Latin American culture and political life. People, and their voices, are always at the heart of her work.