One hundred years ago a handful of soldiers tried to change the history of Brazil. Captured in a photo advancing along the Rio promenade, their suicidal venture ended that day in failure, but its consequences proved to be enduring.

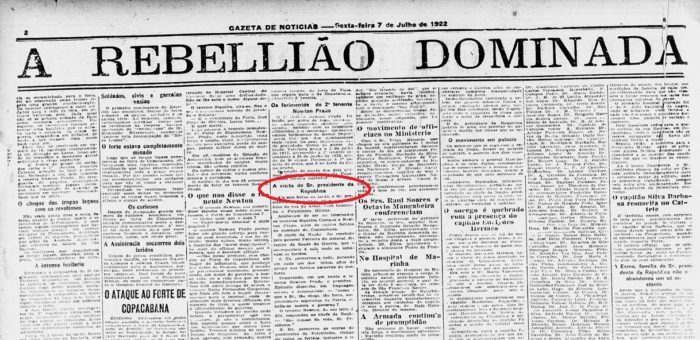

In July 1922 a widespread military revolt was launched, involving hundreds of soldiers based in Rio. They intended to march on the Presidential Palace but their rebellion was quickly suppressed, except for 300 soldiers based at Fort Copacabana. Here they refused to surrender and even used the fort’s powerful guns against the city and Navy warships. The government demanded their surrender, while the Senate approved a state of emergency.

On the morning of 6 July those soldiers at the Fort who wanted to leave were allowed to go, with just five officers and 24 other ranks electing to remain. The most senior officer left to try to negotiate a deal, but was promptly arrested.

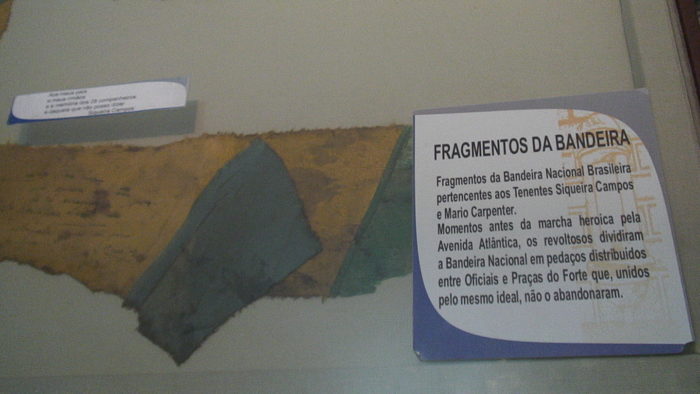

The four remaining lieutenants resolved never to surrender and decided to march to Catete, the Presidential Palace, about 7 kilometres away. They would leave armed but would not open fire first. They also cut up the fort’s flag, so that each could carry a piece of it. One lieutenant wrote on his fragment that he offered it to his parents ‘in defense of what I decided to give what I could … my life’

During their march along Avenida Atlantica, beside Copacabana beach, the rebels gradually lost soldiers, while gaining one civilian volunteer. By this time hundreds of troops loyal to the Government were in position near then Rua Barroso ready to stop them.

A few blocks before they reached the government troops the advance was captured by magazine photographer Zenóbio Rodrigo Couto. This famous photo shows a line of soldiers closely followed by members of the public. Some cheered them on, while others, thinking them mad tried to persuade them to stop. A second photo shows six of the soldiers, probably by now expecting to die, watched by an onlooker on the beach.

At around 3 pm on 6 July the inevitable confrontation took place, when the senior rebel, Lieutenant Siqueira Campos, still refused to surrender. After a shoot-out all the rebels were killed or wounded, but miraculously Siqueira Campos and another lieutenant, Eduardo Gomes, survived.

There were also civilian casualties, while history was denied a filmed record of the event when a camera crew arriving on the scene was caught in the cross fire and their van crashed, killing the driver and wounding two of the crew.

The rebels and their aims

While the four lieutenants leading the march were not drawn from the wealthy elite, they were not poor or uneducated. Though from comparatively well-off families, the fathers of both Siqueira Campos and Gomes had had financial difficulties, which left a military career as the best option for their sons.

The two cadets entered an army that had earlier achieved the transition from Empire to Republic by a military coup and was then seeking to train up an apolitical professional military class. The constitution required their obedience to the President – so long as his orders were deemed to be lawful.

Renting a house outside the Military School, future officers Siquiera Campos, Gomes and their friend Luis Carlos Prestes, established a kind of radical safe house where they could study and discuss politics, and the army’s possible role in defending the nation from a corrupt and unscrupulous oligarchy.

One of the triggers for the rebellion in 1922 was a perceived insult to the military uttered by politicians. Reporters who conducted interviews at the start of the march on 6 July were reminded of that insult and were told that the rebels would fight their way to Catete Palace while defending to the death the traditions of honour and glory of the Brazilian Army. This suggests a movement of young officers concerned with honour and prestige rather than wider political changes.

Little is known about the lower ranks who were caught up in revolt, but the photos suggest some were mixed race or black, reflecting the racial hierarchy of the time. Given the chance, most of the 200 plus rank and file soldiers at Fort Copacabana chose to leave, and of the 24 who remained perhaps six or seven stayed until the final shoot out.

The public response to the rebellion

Before long the rebels were treated as heroes. The wounded lieutenants were interviewed by the press, and even visited by the President while in hospital. A poem about the bravery of the ‘Heroic 18 of the Fort’ was published in a local newspaper, though without much fact checking, as almost certainly the number at the final shoot out was not 18, and possibly as few as 11. While the exact number is still uncertain, the number 18 has endured in descriptions of the event.

As an attempt at regime change, the rebellion was a failure , while the state of emergency gave the government further powers which were used for another four years.

Having attempted an armed insurrection, even shelling government buildings, the two surviving lieutenants were treated leniently, and Siqueira Campos and Gomes later escaped, participating in later rebellions.

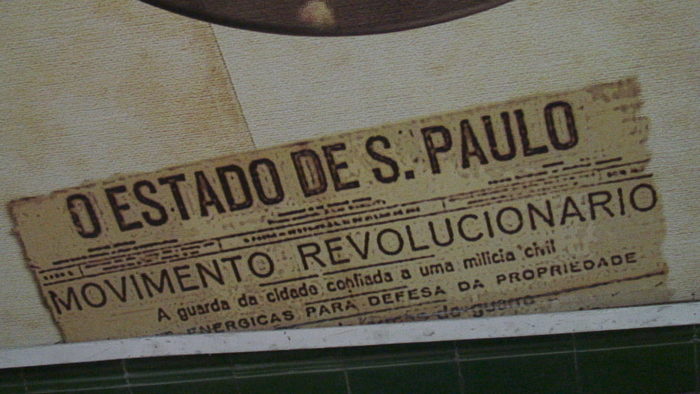

Though a hopeless, even suicidal, venture at the time, the March of the 18 did have long term consequences, helping to set off a chain of events known as the Tenentes (Lieutenants) movement. Tenentes would organise a revolt in São Paulo in 1924, deliberately timed to start on the anniversary of the 1922 uprising, and the subsequent march of the Prestes Column. Better organised than the 1922 revolt, they still failed to change the government or its policies.

Later in 1930 some of the tenentes would be part of a significant re-shaping of Brazilian politics, which brought Getulio Vargas to power. It has been claimed that neither the events of 1930, nor those of 1964, would not have been possible without tenentism, which in turn was shaped by the 1922 March of the 18..

During the 1920s many junior army officers were influenced by the example of the 18 of the Fort. After 1930 former rebels were able to resume their military careers, joining others who had remined loyal, creating the military that would go on to play a crucial part in Brazilian politics, notably during the dictatorship. Some like Gomes would rise to senior positions. Another rebel, imprisoned in 1922, was Lieutenant and later President Costa y Silva.

What is left today

A few years ago, I traced the route taken by the 18 and visited the Fort, complete with the guns that once bombarded Rio, between Copacabana and Ipanama beaches. It has an 18 do Forte café, and a museum which displays pieces of the flag carried that day. Outside is a plaque featuring Cuoto’s photo.

Rua Barroso, where government troops lay in wait for and attacked the rebels, is now Rua Siqueira Campos. Nearby is a statue of a falling soldier, erected in 1974 during the dictatorship years, It includes a list of 18 names, sustaining the story of that number – though probably a third of them would not have been shot here – and words attributed to Siqueira Campos, ‘We must give all for the homeland, asking for nothing, not even to be understood’.

The mosaic wave design on the promenade captured in Cuoto’s photos can still be seen on the Ave Atlantica today, though the Hotel Londres, where the rebels stopped for refreshments, and a few soldiers took the chance to flee, is long gone, replaced by the some of the many sea-front skyscrapers. Filming near Rua Siqueira Campos in Rio may still have risks, as barely a block from a beach full of tourists, I was quickly advised to hide my camera to avoid robbery, or worse.

After 1930 the surviving lieutenants’ names started to appear in the names of streets and schools, and later a municipality in Parana and Manaus airport.

The Presidential Palace has moved to Brasilia, now occupied by a President with his own links to the military, forced out as rebellious junior officer but never allowed back into the ranks. Nevertheless, Bolsonaro’s presidency has seen the military more embedded within government than it has been for decades. With national elections only months away, Brazil has a polarised electorate, deep institutional crises, and rampant speculation about how the military may react.

Whatever changes the tenentes hoped to achieve, 100 years later endemic problems such as homelessness remain in cities like Sao Paulo. I recently came across a group them camping in Ave Paulista, near the park usually known as Trianon. Probably few of these homeless people, or the shoppers, tourists and others passing by, know that the park was renamed in 1931, after Tenente Siqueira Campos.

Main image: the iconic photograph of the 18 of the Fort