In late April 2022, the body of Ulises Rumiche Quintimari was found on the Naylamp de Sonomoro highway, that cuts through Peru’s Junín province, located in the nation’s central highlands. The indigenous leader’s death came just hours after he had met with the deputy minister responsible for vulnerable populations and women. As part of his work, Ulises had championed sustainable development projects in Peru’s VRAEM (Valle de los Ríos Apurímac, Ene y Mantaro) – an area covering the Ayacucho, Junín and Cuzco regions that has long been associated with illegal cocaine production. Shining Path guerrillas previously worked as ‘armed escorts’ for cocaine passing through the jungle region, posing great risk to those who stand in their way.

Just weeks before Ulises’ death, two Asháninka defenders from the Cleyton community and one Yanesha defender from the Santa Teresa community were assassinated in the province of Puerto Inca, located in Peru’s central Huánuco region. Those behind their murders are thought to be linked to mafia-style groups dedicated to drug trafficking and illegal mining active in the area. Illegal gold mining by prospectors linked to such groups has long been a problem for the hamlet.

Indigenous rights organizations claim that the recent killings show the ineffectiveness of protection systems currently in place for defenders. In a joint statement, the department of Ucayali’s Regional AIDESEP Organization (Organización Regional Aidesep Ucayali – Orau) and the Regional Association for Indigenous Peoples of the Central Jungle (Asociación Regional de Pueblos Indígenas de la Selva Central – ARPI-SC) lamented that ‘the value of human life and … of indigenous life has been completely lost.’ The two organizations added that Peruvian authorities ‘do not implement effective protection systems’ for defenders, labelling mechanisms in place as ‘insufficient’ and ‘inappropriate.’ In turn, they rejected violence facing their communities ‘caused by illegal activities empowered by … [the] corruption of state authorities that are charged with promoting justice [but instead] ensure impunity.’

Meanwhile, the Interethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Jungle (Asociación Interétnica de Desarrollo de la Selva Peruana – AIDESEP) stressed that ongoing attacks demonstrate the inability of the State to protect defenders and guarantee security for communities.

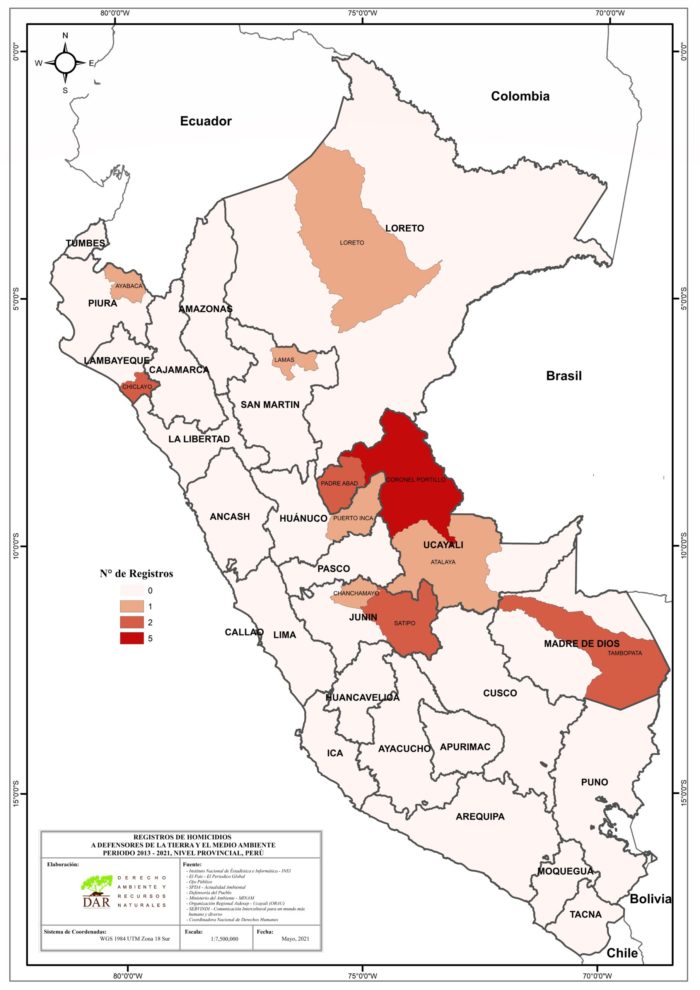

Indeed, in Peru, defenders working to protect their local environments and territories are facing ongoing and increasing threats underpinned by impunity. Since 2020, there have been 19 reported killings of environmental and land defenders in the country’s Amazon region.

Defenders have largely been targeted for their work to halt drug trafficking, illegal logging and land grabbing in the territories they seek to protect. Coca production has spread across Peru’s Amazon, with landing strips for drug flights that drive deforestation an ongoing issue in Ucayali, Loreto, Huánuco and Pasco, according to a recent investigation by InSight Crime. Meanwhile, hardwoods like cumala and tornillo used in the production of luxury furniture for local sale are felled, while cheaper lightwoods like balsa (used in the production of wind turbine blades) are also targeted by organized networks of timber traffickers for overseas sale.

In many cases, these activities have expanded in territories where there is little, if any, state presence. Access to state institutions for defenders and their communities is often limited and, where present, corruption in such institutions is an ongoing obstacle. Beyond this challenge, environmental defenders also face smear campaigns, exclusion from decision-making fora, criminalization, threats and attacks.

Fighting For Land, Their Lives

In December of 2021, members of the La Paz de Pucharini community in the district of Puerto Bermúdez, located in Peru’s central Pasco department that lies just below Huánuco, found the body of Asháninka leader Lucio Pascual Yumanga, with bullet wounds. As a community leader, he had been working to keep drug trafficking out of La Paz de Pucharinil, which is found in the El Sira Reserve – an area long threatened by the encroachment of illegal activities. From the illegal logging of cheap bolaina wood used in construction, to coca cultivation, communities living in the area have been fighting both to keep illicit activities off their lands and for the legal recognition of their territories so that their collective rights are recognized.

Lacking land titles increases the vulnerability of environmental defenders in Peru’s Amazon, particularly where the central departments of Huánuco and Pasco intersect with eastern Ucayali. In many cases, individual land titles for plots within indigenous communal territories have been granted to outsiders. Some recipients are rumoured to have links to illegal economies, particularly drug trafficking. According to the office of Peru’s Ombudsman, the indigenous communities most affected by this dynamic are the Asháninka, Cacataibo, Shipibo Conibo, Awajún and Wampis.

Herlin Odicio knows this all too well. As President of the Cacataibo Federation (Federación Nativa de Comunidades Cacataibo – FENACOCA) and member of the Padre Abad provincial council in the eastern department of Ucayali that borders Brazil, he has been the target of repeated threats to his life, despite the fact he is supposed to be under protection.

As a result of Odicio’s efforts in collaboration with others, the Peruvian government formally established the near-150,00 hectare Cacataibo Indigenous Reserve to protect indigenous people in voluntary isolation. However, the leader’s work has placed him at odds with drug traffickers and other illegal actors in the area. Odicio recounts being approached by a drug trafficker, known as ‘Fernández,’ who unsuccessfully tried to convince him to help multiply drug shipments out of remote zones of Cacataibo communities for a lucrative fee. When discussing how, instead of collaborating, he opted to hand over information to local authorities on where local mafia-style groups operated. Odicio explained: ‘I could have left it there and shut up. But… they advance, and they will not stop killing us. We had to start telling the world that indigenous peoples do not live happily. If, years ago, leaders had denounced, today we would be walking calmly.’ Threatening text messages were quick to follow.

The threats facing Odicio have continued to escalate. In November 2021, over 24,000 hectares of indigenous territory were invaded by coca growers in just three Cacataibo communities across the central Huánuco region, where clandestine airstrips facilitating drug flights to Brazil or Bolivia and cocaine laboratories have also been detected.

Justice?

Most killings of environmental defenders in Peru go unresolved. However, there has been progress towards justice in some instances.

For example, it was recently announced that the trial of Cacataibo leader Arbildo Meléndez’s alleged killer would begin. The Native Federation of Cacataibo Communities (Federación Nativa de Comunidades Cacataibos – FENACOCA) welcomed the news but added that ‘if the State does not act as it should,‘Cacataibo justice’ will be applied. A representative from the organization added: ‘we ask the Peruvian State to act with great respect for Arbildo Meléndez, who left behind four minors… who have not received justice so far.’

Prior to his assassination in April 2020, Meléndez had long championed the right of the Cacataibo communities to receive titles for their lands in the face of land grabs linked to drug cultivation and land trafficking, as well as incursions by illegal loggers. His death came soon after he had given evidence to the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders.

Also in April 2022, eight years after the assassination of four Asháninka leaders who had denounced illegal logging in the Saweto community of eastern Ucayali, legal proceedings commenced against three suspected killers and two logging entrepreneurs, accused of orchestrating the murders. Tornillo, cedar and copaiba trees, among others, have all been targeted by loggers in the area. In this case, the suspects are expected to be sentenced at the end of October, according to reports from Ojo Público.

Peru’s government has also taken positive steps to enhance protections for environmental defenders, through the adoption of fresh legal frameworks and important policy changes.

Increased cooperation between eight ministries, including the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights, Ministry of Energy and Mines and Ministry of the Interior, among others, to prevent human rights violations against defenders, promote their work and ensure they have access to justice has also been a central goal.

In April 2022, the government published a supreme decree to improve this coordination. The decree specified specific actions that government agencies should take and outlined procedures to identify those in need of protection. It established an ‘early warning system’ to improve available protections and emphasized the importance of providing technical assistance to regional and local governments to achieve this.

Nonetheless, there is still a long way to go. While measures to support defenders have been welcomed by civil society, many believe that their implementation has been limited. There are also serious concerns about continued delayed responses to the threats defenders receive. It remains to be seen how effective the promising supreme decree will prove to be.

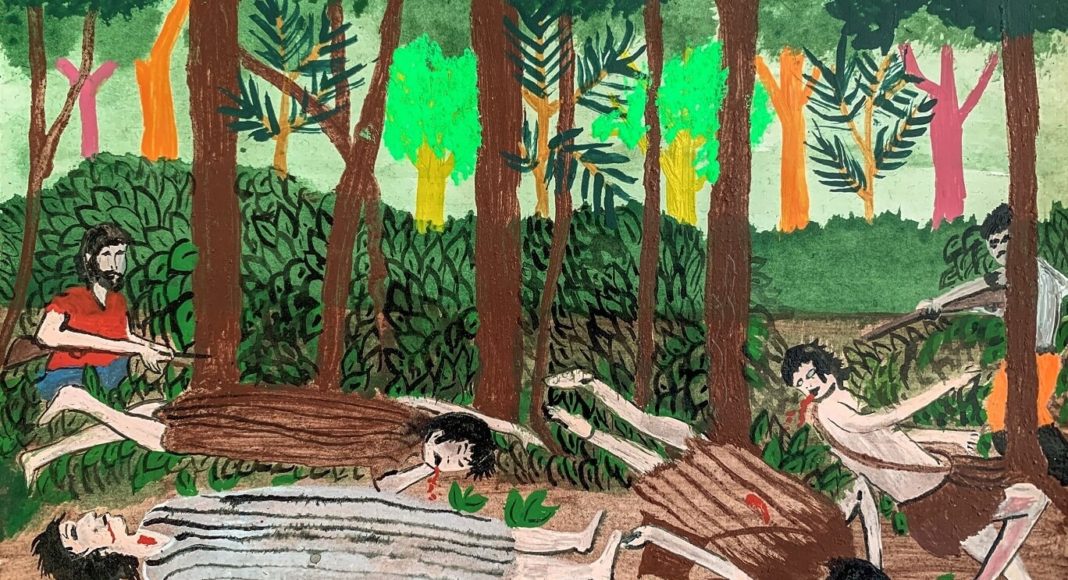

Main image: ‘FEAR: The Asháninka communities in the Tamaya basin are not denouncing the illegal [loggers] for fear of being murdered. Image: Asháninka artist Enrique Casanto Shingari