The sound of sabres

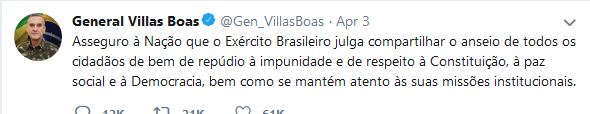

A retired general declared that a decision in Lula’s favour would encourage violence, and if Lula were allowed to run for president there would be no alternative but military intervention to ‘restore order’, with the crisis being solved with bloodshed and bullets. Another general, who seemed to think he was still in the 19th century, tweeted that he was booted and spurred, his horse saddled, ready to follow his chief.

Radicalization

The consequences of the Supreme’s narrow decision against Lula could be a ramping up of the radicalization which has already led to violence against the ex-president and other leftwing parties. Lula’s recent campaign tour in the southern states of Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina and Paraná was met with organised hostility in many places – not just barrages of eggs and stones but in one place bullets were fired at the buses and, in another, barricades were erected to stop him entering a town. The leadership of the Workers Party (PT) held an emergency meeting in São Paulo to discuss the supreme court verdict. Video: Jornalismo SBT/Youtube This radicalization is encouraged by the lame duck government of Michel Temer, more concerned with saving his own neck than saving Brazilian democracy. Temer had thought he was out of the woods, and even begun to talk about running for re-election, but a new accusation by Chief Prosecutor Raquel Dodge which involves him and a group of his close friends in a corruption scheme at the Port of Santos, could lead to another attempt to get him impeached in Congress. This time several of Temer’s friends and collaborators, including a retired military police colonel, were temporarily detained for questioning. With practically all the president’s men, both ministers and now friends, accused of corruption, Temer’s political future looks bleak. Although as he has shown before, he is remarkably resilient, or perhaps impervious, shaking off the flood of accusations, incriminating e-mails, recordings, videos, etc., like a real duck.Saving skin

This time, however, congressistas facing the ballot box in October will probably be more interested in getting re-elected than in saving Temer’s skin. And Rodrigo Maia, speaker of the Chamber of Deputies, himself a potential candidate, might relish the chance to stand in as president for the last months of Temer’s term, from where he can conduct his own campaign, pen in hand. Unable to approve any reform in congress that would reduce the government’s deficit, but instead pouring money into attempts to buy support, Temer’s prestige in the business and financial community is also at rock bottom. Lula’s supporters on the streets. Video: Telesur/Youtube Brazilians can now choose between following the real-life drama involving corrupt politicians, melodramatic court judgements, and federal police raids on posh mansions and offices, and a thinly disguised fictional version in a Netflix serial entitled The Mechanism, involving corrupt politicians, melodramatic court judgements and federal police raids on posh mansions and offices. Director Jose Padilha has spiced up his version with lots of sex, but has been criticised by the PT for putting MDB senator Romero Juca’s infamous phrase ‘we must stop the bloodletting’ -interpeted as a threat to the Lava Jato investigation – into the mouth of the Lula character.No justice for Marielle

Meanwhile, over three weeks after she was killed, the police have failed to produce any information about PSOL councillor Marielle Franco’s killers. Two people who witnessed the crime have not even been questioned, while all Marielle’s aides, colleagues and friends have been intensively interrogated. Experts agree that it had all the hallmarks of a political crime, carried out by professional killers.

The contradictions and ‘schizophrenic posture’ in the procedure and verdict of the Supreme Court are analysed by Aury Lopez Junior, professor of Criminal Law at the Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul (read here, in Portuguese). He highlights the way in which the judges avoided ruling on the central issue: whether it is constitutional, in Brazil, to enforce a sentence of imprisonment while an appeal is pending. He mentions, in particular, the contradictory position of judge Rosa Weber: “é um imenso paradoxo dizer que é contra uma execução antecipada e negar um habeas corpus no qual se discute a execução antecipada”