In 1924 following an uprising in São Paulo a military rebellion broke out in Brazil against the oligarchic rule of the First Brazilian Republic. The most conspicuous part of the revolt was the formation of the Coluna Prestes, some 2,000 strong at its peak, which completed an astonishing 25,000 km march through the Brazilian countryside, avoiding direct confrontation with federal government forces, but aiming to provoke further mutinies and social uprising.

Malcolm Boorer has traced the history of the rebellion in two previous articles for LAB, the first about the column’s arrival in Pernambuco with the hope of an uprising in Recife; the second about the quixotic ‘18 of the Fort’, who in 1922 anticipated the revolt with a mutiny in Rio de Janeiro.

This third article charts the Column’s actions in Bahia in 1926.

Chapada Diamantina covers a large area (greater than Wales) in Bahia State in north east Brazil, much of it national park and now very dependant on tourism. Not far from the town of Lencois is Pai Ignacio Mountain, a popular attraction providing magnificant views of an area once the preserve of backlands strongmen known as Coronels and briefly the route of the Prestes Column.

The Column had already survived a year of its war of movement, marching around inland Brazil. Having failed to start an uprising in Permanbuco it arrived in Bahia in April 1926. Then numbering more than a thousand troops it sought recruits and supplies, in the hope it could then advance on the Government in Rio.

At that time this part of Bahia was a poor area subject to Coronelismo, the rule of Coronels (colonels), who exercised near feudal powers in the backlands of Brazil. This is the power structure described in Jorge Amado’s novel Gabriela, Crabo y Canela. Visiting Lençóis earlier this year I found an exhibition pointing out that the coronels together with their jagunços (armed security men) ‘transformed Chapada Diamantina into a battlefield at the beginning of the 20th century.’ By the 1920s the local strong man was Horácio de Matos, who fought against federal and state governments so he could control this area. The exhibition described him as being prone to violence but ‘a defender of peace in the hinterland and of moral values’.

The Prestes Column hoped to make an arrangement with Matos but made the mistake of killing some of his relatives. Matos then sided with the government and formed Patriotic Battalions, and according to a tourist guide I was given, he ‘set off with 600 men, pursuing the Column for six months’. The local press also demonised the Column with exaggerated stories about its misbehaviour.

Many local residents tried to escape from its path, but some fought back, harassing and ambushing the rebel soldiers, and by the time they reached the neighbouring state of Minas Gerais their campaign had become unsustainable. Backtracking through Bahia, loosing more troops on the way, and exacting more retribution on the local population, the Column then headed for exile, still pursued by jagunços, undefeated but no longer capable of winning. Bahia proved to be the most difficult part of their long march.

A mystery, a miracle

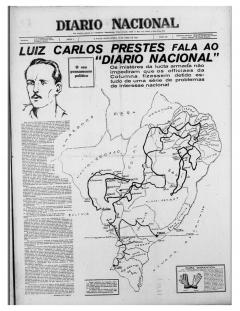

While the rebel Column was loosing militarily in Bahia, it started to win the propaganda war. Just weeks after leaving Bahia, an eight part series about the ‘Columna Prestes’ started in a Rio newspaper describing it as ‘a mystery and, at times, a miracle……. undaunted and triumphant, without being defeated.’ And it was already named after Prestes, who would become known to history as the Cavalier of Hope, not after its commanding officer, the now largely forgotten Miguel Costa.

The story of the Invincible Column, the grand march that gave hope to the backlands of Brazil, was helped by effective narrative management, with officers giving press interviews after they reached exile in Boliva, and later writing their memoirs. Years later researchers started to publish the stories of those now elderly people who found themselves in the path of the Column. They remembered destruction, killing and looting caused by these ‘revoltosos’. Compared with the violence endemic in places like Chapada the Column may not have been the worst offender, but necessity of feeding over a thousand men was bound to generate tensions with the local population, exacerbated by the indifference, fear and resistance they faced.

Later researchers also heard the stories from the Column’s foot soldiers. In the 1990s one of them noted that ‘drunkenness was almost constant [as we passed] through the rivers and backlands of a country that seemed to have no end.’, not quite the view advanced by Prestes’ daughter who wrote about her father’s approach of encouraging education and literacy among the troops he commanded.

In its few weeks in Bahia the Column achieved little other than uniting government and irregular fighters, and adding to the violence and destruction. Coronelismo and the rule of people like Matos continued until the 1930 revolution, which was supported by most former Column leaders, and which led to the demise of Matos, along with the Old Republic.

The PT hang on in Bahia

Today the State has a greater presence in places like Chapada, with Rui Costa of the PT, Lula’s party, completing an eight year term as Governor. When I visited Bahia in June, and for the months since, in the lead-up to the October elections, polls suggested that former Salvador Mayor ACM Neto of the União Party would easily replace him. Neto is part of a family dynasty, his grandfather a previous State Governor, and the family own state wide TV radio and newspapers. But the polls were wrong, and Jeronimo Rodrigues, of the PT, was elected as the State’s first indigenous Governor. And like most of north east Brazil, Bahia voted strongly for Lula.

Visiting Lençois I soon learnt about local diamond mining, which created great wealth in the 19th century. After widespread environmental devastation mechanised mining was stopped in the mid 1990s, and many poor people continue to survive on subsistence agriculture, while traditional land owners,still own vast tracts of land.

Much of the area is now a National Park, and tourism, helped by a 1992 telenovela (TV soap opera) partly filmed in Lençois, is a vital part of the economy. The Covid-19 pandemic led to a strict local lockdown and the suspension (now ended) of flights to the local airport. I was assured that hotels and restaurants in town would soon be full with long queues at attractions like the Gruta Azul (Blue Cave).

Nearly 100 years ago and not far from Gruta Azul, the Column’s detachment led by Siqueira Campos arrived at a hamlet then called Agua de Rega, to be met by gunfire from the residents. In Bahia the revoltosos did not get the recruits or supplies they sought, and lost probably a quarter of their number. Returning towards exile a few weeks later the column burned and looted more homes around Agua de Rega. While poor people in Bahia suffered, the Prestes Column went on to establish its reputation in history.