On 19 March towards 7.30 p.m., I receive a WhatsApp message from Pedro, one of my main contacts for my PhD research in Buenos Aires. ‘Is it true that they declared the quarantine’, he asks. ‘Yes, until 31 March’, I type. I had just read the newspaper headings announcing what many observers had assumed for days: President Alberto Fernández declared the ‘preventive and obligatory isolation’ until the end of the month, starting at midnight.

People are only allowed to leave their houses for urgently necessary tasks, such as going to a supermarket or pharmacy. Only those employed in a few specific sectors, such as health and the police, are allowed to continue working. ‘Uh, I will be without money’, responds Pedro. ‘Didn’t you just receive your pay?’ ‘Yes, but I had to pay the hotel’.

‘We can’t afford a fine’

On the following day, Pedro tells me that, shortly after the president’s declaration, he received a message from his employer: ‘She told me that tomorrow it would be closed, that on Monday they might open, who knows? But it’s impossible. If you leave your house, you can be arrested … and they can impose a fine. And we can’t afford a fine.’

When I met Pedro in 2018, he had just lost his job and was trying to make ends meet by selling empanadas and going through the bureaucratic hurdles to enroll on various welfare plans. After months of fruitless and frustrating job-search, he finally found work in the kitchen of a restaurant in northern Buenos Aires where he worked until today – however, without a contract of employment. He is paid by the day, and if he does not work, he is not paid.

Since the death of his ex-wife, Pedro is a single parent. Together with his 14-year-old son he lives in a so-called hotel familiar in southern Buenos Aires. Such hotels let rooms by the month; Pedro and his son live in a single room and share a bathroom and kitchen with the other hotel inhabitants. For many people, hoteles familiares have evolved from a transitory to a permanent place of residence. Pedro, who moved from Salta province in northern Argentina to the capital in the 1990s, has been living in hotels for many years. Like others, he lacks the means to rent a flat, because most landlords not only require a deposit payment but also a real estate or bank guarantee, to which Pedro has no access.

Taking precautions

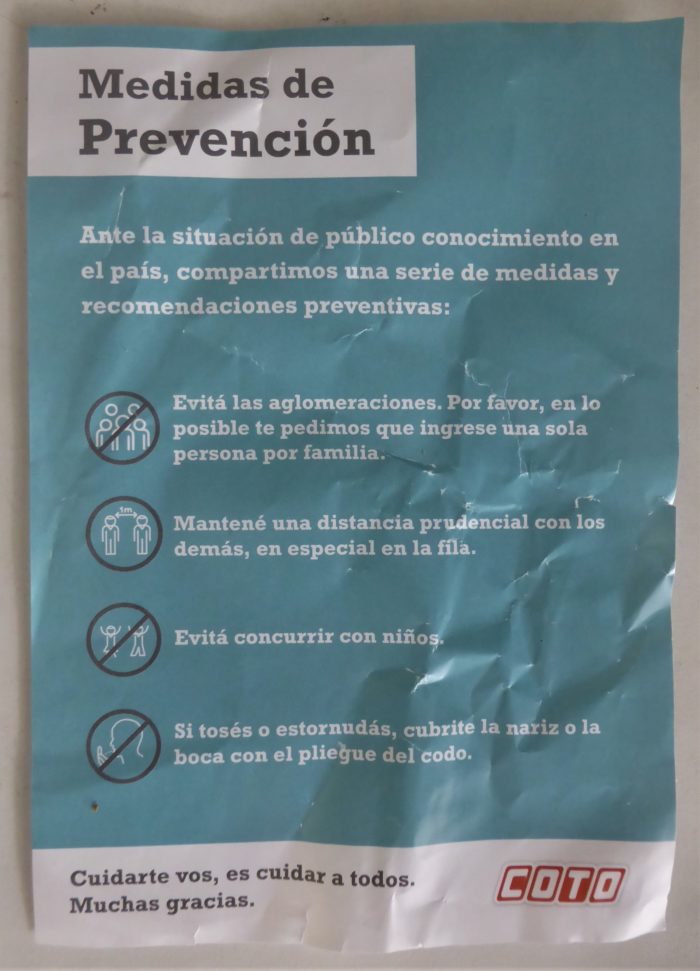

Pedro’s son has been off school since all schools were closed by presidential decree on 15 March. While Pedro was at work, his son stayed at home alone, doing homework that the school sends Pedro by email and that he receives on his smartphone. Now, Pedro and his son are both at home. Pedro tries to keep the house as clean as possible and has forbidden his son to touch anything in the shared kitchen, precautionary measures that, he believes, might help keep his son healthy.

Pedro does not question the necessity of the emergency measures per se. The prospect of a virus spreading in Argentina frightens him, and for him the ‘threat’ (amenaza), as Fernández called the epidemic in his speech, has become more real as emergency policies come into force. ‘Until last week, I didn’t really believe in this. But then I realize that what is happening now is really serious. At this moment,’ he continues, ‘I worry most about my health, the health of my family, of my son. The economic situation comes second.’ His partner lives in another part of the city. Probably, she could still join him and his son, because there are buses, even if they only transport one passenger per seat. But Pedro fears that his partner might risk infection if she travels by bus.

#YoMeQuedoEnCasa?

In theory, Pedro subscribes to the president’s request to stay at home, as do many of the people I have talked to in Buenos Aires. The hashtag #YoMeQuedoEnCasa (#IStayAtHome) that has been spread all across the Spanish-speaking world has also been massively shared by Argentine influencers and appeared on many Argentine websites. However, the very reasonable question ‘Stay at home: who does that apply to?’ (Ficar em casa para quem?) that Willians Santos asks in his article on the (im)possibilities of staying at home in the highly unequal Brazilian society is also relevant in Argentina. Structural inequalities ensure that not everyone has the same options. Being able to stay at home can be a privilege, even though it was scarcely being valued in that way by all those who treated their days off work as a holiday and set off to Pinamar and other Argentine seaside resorts.

There are many structural reasons that make it difficult to abide by the curfew, just as there are also personal stories and coincidences. For Pedro, the emergency measures related to COVID-19 come at a particularly inopportune moment. He always has to calculate his incomes and expenses, but especially now, this year. In February, he travelled to visit his family in his hometown in Salta province, a visit that was not only costly because he paid plane tickets for himself and his son, but also because, in his role as a rural-to-urban migrant returning home for a visit, his family expected him to pay part of their expenses. Moreover he took his partner with him to introduce her to his parents and in obedience to the gendered expectations that place the man as the provider, he paid all her expenses as well.

After his costly home visit, Pedro had to borrow money to pay his monthly rent of 8,000 pesos, and now faces several days without income. As for the next month, he will try to negotiate with the hotel manager to pay his rent in two parts, ‘to tide me over for a while’, as he says. On the telephone, he asks me if I can lend him 1,000 pesos to buy some food. He leaves his house despite the curfew. If there are any police about, he will tell them that he is just going to the supermarket next to my house, he says. As he walks towards my house, I see that he holds a shopping bag pressed ostentatiously against the backpack which he has turned to the front. Two police officers stand on the opposite side of the street but pay no attention to us.

Later, on

the telephone again, after we have talked long about how unsettling the

Coronavirus epidemic seems to him, the lack of a cure, the perspective that

there will be many more infections, he suddenly says: ‘Today, I feel afraid.

This situation that we are living through now, I didn’t see it coming. I have never

experienced anything like that. Never. Not in Salta, not here, either. It’s the

first time that I feel like this. That I’m afraid of ending up with nothing,

not even a roof, a house.’ On this first day of curfew, there is the fear of Coronavirus

and for the health of his family, the uncertainty whether and how the virus can

be countered. But the emergency measures also expose the precariousness of his

living and working conditions and these things combine, for Pedro, into an

unprecedented feeling of existential threat.

Franziska Reiffen is a social anthropologist from Mainz University (Germany) and currently conducting fieldwork on migration and, more generally, life in precarity in Buenos Aires, Argentina – at least as far as possible in times of Coronavirus-emergency-measures.

All names of persons interviewed have been changed.