Almost three years of hope and optimism for change in Chile came crashing down with an overwhelming rejection of the Carta, the new draft constitution, last night. Only a few hours after polling closed, it was clear who had won. The Rechazo (reject) camp gained almost 62 per cent of the obligatory vote, with a majority in every region in the country. Only the Chilean ex-patriate population voted in favour of the proposal.

The result was in some ways surprising – the proposed constitution offered a much-needed overhaul to key themes, including healthcare, education, and pensions. These were major issues raised during the 2019 protests that led to the constitutional process. Thursday’s closing of campaigns ceremonies also saw hundreds of thousands gather in Santiago’s Alameda for an event in support of the new constitution, compared to only a few hundred at the Rechazo camp.

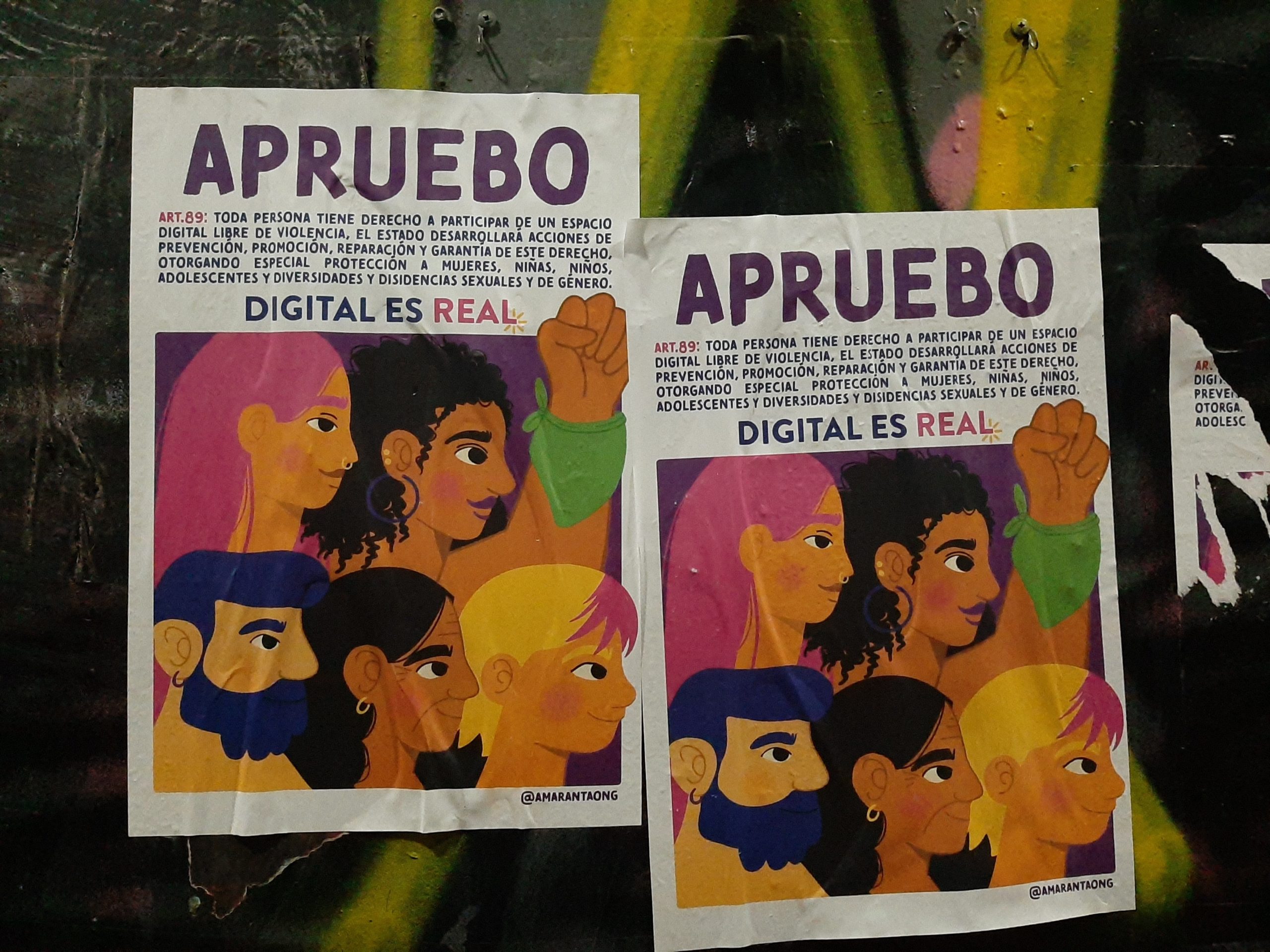

Apruebo propaganda often appeared wordy, worthy and tentative

However, the last-minute show of support for Apruebo (approve) was not enough to counter the Rechazo camp’s successful, albeit fear-mongering, campaign; with copious amounts of false information spread on social media leading to a loss of faith in the Constituent Assembly.

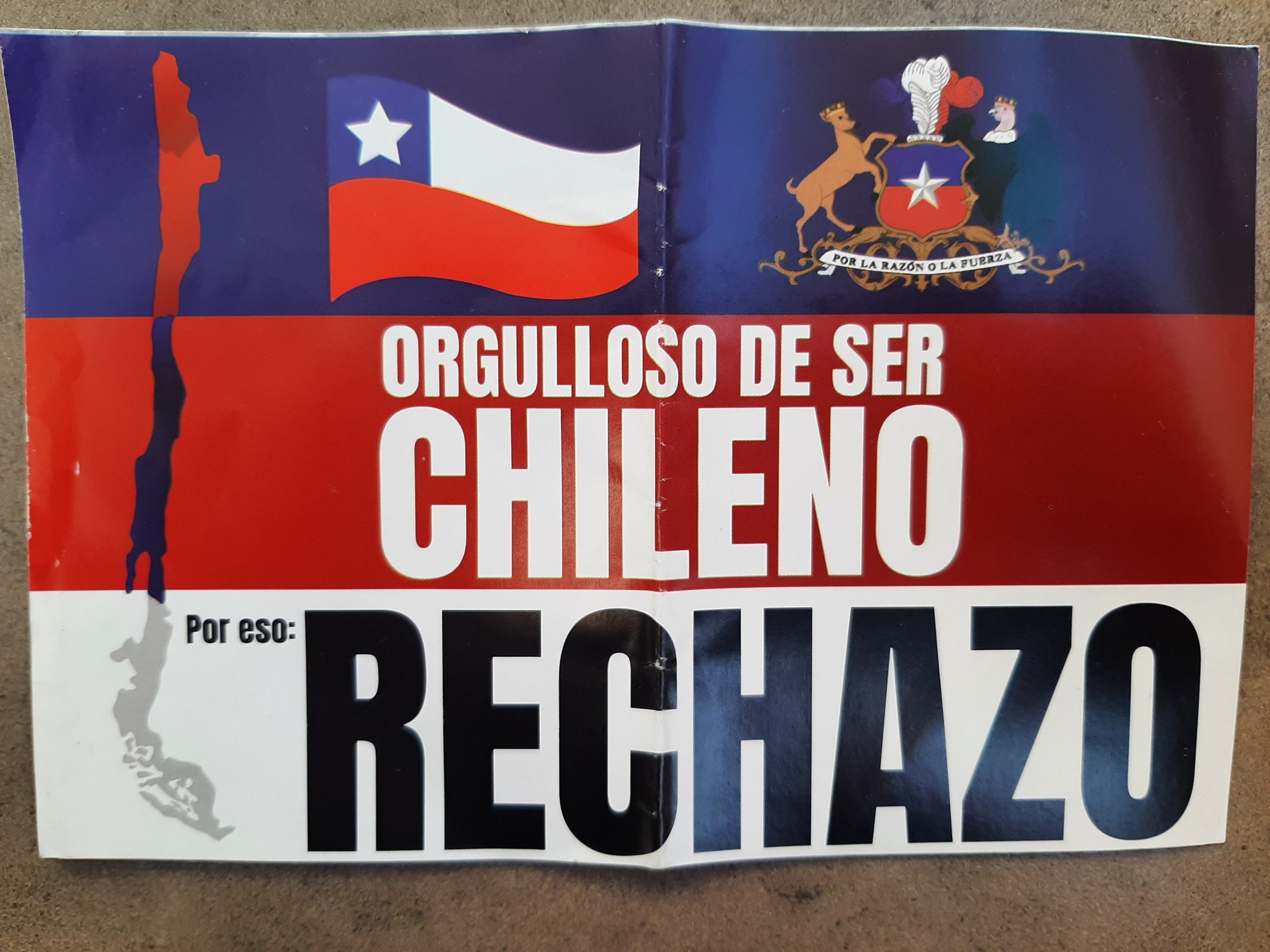

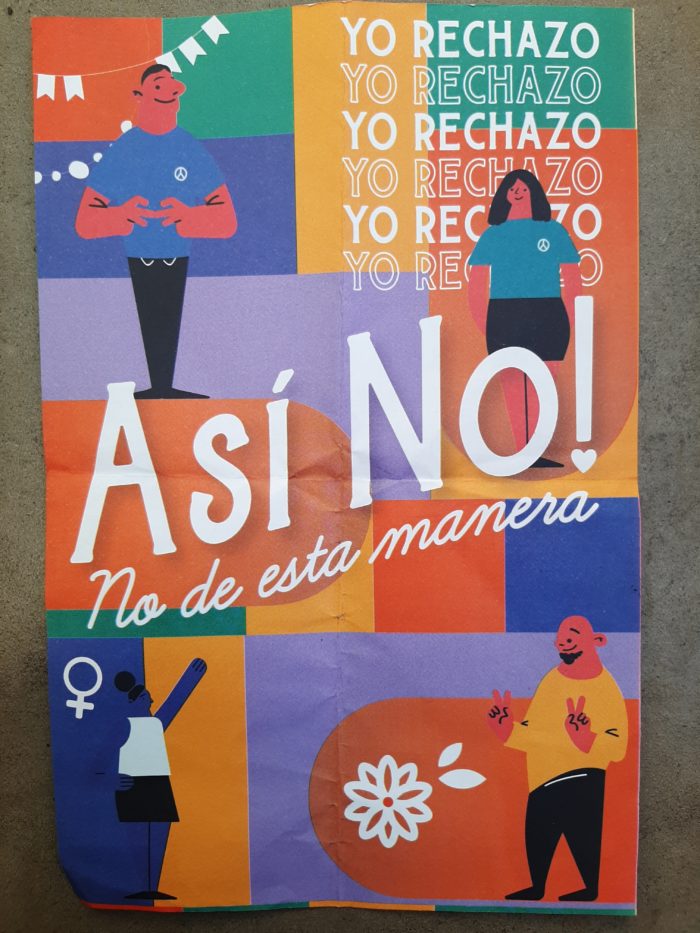

By contrast, Rechazo signs and slogans were often brief, clear and persuasive

The Constitutional Assembly

The Constitutional Assembly was initially hailed as a milestone for democracy. It was made up entirely of civilians, as determined by the initial referendum in 2020. The elected constituents came from all walks of life: amongst them doctors, lawyers, teachers, ex-politicians, activists.

In a world first, the assembly guaranteed gender parity – half the seats would be for women, and half for men – as well as seats for representatives of Indigenous peoples, proportional to the population. It was a stark difference to the commissions that wrote the existing 1980 Constitution: they had been carefully picked friends of the Pinochet regime. Only one woman, Mercedes Ezquerra, was present in the final commission that finalized the 1980 Constitution.

However, the modern Assembly suffered a host of scandals which served to undermine its legitimacy. One constituent, Rodrigo Rojas Vade, was caught having lied about a cancer diagnosis. He had used during his election campaign to show that he would better understand the Chilean medical system. Insults were openly thrown between constituents in the chamber, while others showed a clear disdain for the process, unaware their microphones were switched on and being recorded. Nicolás Nuñez, another constituent, requested to vote on an article while he was in the shower.

Considering the constituents earned up to six times the median wage in Chile and, on too many occasions, showed that they did not take it seriously, their blunders made a laughing stock out of the most important event in the country for 30 years. It left a sense of bitterness, disappointment, and incredulity in the air.

False information

False information, something of a guaranteed factor in modern elections, was no stranger to this referendum. When a country’s entire legal framework is up for play, without the definitions of the corresponding laws, it is easy to play on people’s fears.

Entirely privatized and with payments purportedly calculated on a life expectancy of 110, the majority of Chileans believe the pensions system in Chile is flawed. The proposed constitution guaranteed ‘the right to age with dignity’, including ‘sufficient social security payments for a dignified life’ (Article 33). However, without any precise laws, it was open to misinterpretation. On social media, many fanned the flames of claims that the Government would expropriate Chileans’ hard-earned savings, divert them for other purposes and prevent people from bequeathing their fund to children and family.

Similarly, the draft provided greater guarantees for private property than the existing Constitution. However, when the changes would be made under comparatively radical left-wing government, it didn’t take long for opponents of the draft to claim that ‘if the constitution is conceived under collective equality, your right to property is at risk’.

Fear-mongering

Fears were not limited to the alleged threat to pensions and properties. A third key issue was Chile’s unity, as much territorial as in spirit. Rumour and criticism ignored the Carta’s careful provisions for Chile’s territorial make-up and focused on two other issues.

The first was the proposal to create regional parliaments. Instead of the House of Senators in Santiago and the House of Deputies in Valparaíso, there would be a House of Deputies in the central region, and a smaller House in each region. The intention was to create a faster, more dynamic, and de-centralized system of government for a country that stretches 2,600 miles from the tropics to Antarctica, with varying cultures, climates, and economies in between.

Nonetheless, without any precise details of how the chambers would work, counterarguments suggested it would lead to an imbalance of power, or as ex-President Eduardo Frei suggested, even a dictatorship – powerful words in a country that’s trying to re-write a dictatorship-era constitution.

The second, and probably more potent factor, was the recognition granted to Indigenous territory (article 234) and Indigenous judicial systems (article 309). These would have allowed for the 11 named Indigenous Nations to manage their own security and business in the region, with the potential to decrease tensions and violence. The current constitution does not recognize any of the Indigenous nations living within Chilean territory.

However, the proposals seriously underestimated the effects of years of mounting conflict between Mapuche groups and the State in the south of the country. Less than two weeks before the election, Héctor Lliatul, the leader of the radical militant group Coordinadora Arauco-Malleco (CAM), was arrested along with his son, on charges ranging from calling supporters to take up arms to arson and attempted murder.

Chileans, long influenced by deeply negative reporting of indigenous groups in the mainstream press, genuinely fear what would happen if these groups were granted power or autonomy. In fact, the five regions that saw the most votes for Rechazo lie in the Macrozona Cento-Sur and Macrozona Sur – the regions closest to the conflict. Would violence increase? Would Indigenous people be able to attack non-Indigenous, and gain favour in their own courts? Would they seek independence, or try to take over the rest of the country? These were the questions on many Chileans’ minds.

What’s next?

The referendum was a simple two-option vote: ‘I approve’ or ‘I reject’. Of the 388 articles contained in the proposal, it only took a handful, or perhaps just one article to convince a voter to reject the whole thing.

A key strategy of the Rechazo camp’s campaign was to proclaim: ‘Así No’ [Not like this], rather than just a blanket ‘No’. They do, at least superficially, still want to change the constitution.

This morning, Chileans woke up to the same country they were in yesterday. After last night addressing the nation and stating the importance of listening to the voice of the people, President Gabriel Boric called a meeting with party leaders this morning to discuss how to continue the process. For him personally, and his government, which had greatly favoured ‘Apruebo’, the vote is a major setback. For now, however, the idea of change is preferred over change itself.

The crucial question, not just for Boric, but for the entire Chilean people, is: if not ‘Así’, then precisely how? And more than that, how to find a way forward that can assuage the fears that the rejected draft Carta gave rise to? Failure now to find a way presents Chile with a prospect of deepening divisions and uncertainties. All those who mobilised and sacrificed so much during the 2019 estallido social are unlikely to tamely surrender their determination to obtain real change.

The draft constitution can be read here.