Jan Rocha is LAB’s Brazil correspondent and has been writing for us, the BBC and the Guardian from São Paulo for more than forty years. In this impassioned plea, from a city which in August 2019 was made dark at midday by the smoke from the burning Amazon rainforest more than 1,600 miles away, she asks: ‘Is this a war against the future of the world… the war to end all wars.

Wars are going on all over the world, not just in Ukraine. But few people realize that what is happening in the Amazon is also a war, a war against the rainforest and its original inhabitants and, in effect, a war against the future of the world. Perhaps this is the Third World War, the war to end wars.

The weapons are not bombs and heavy artillery, but tractors and bulldozers, excavators, dredges, chainsaws. It’s not trenches that are dug, but roads. And it’s not napalm that is sprayed, but pesticides.

Every second, 18 trees are felled. Every minute, the equivalent of five football pitches is cleared. Systematically the rainforest is being razed, burned and transformed into cattle pasture and soy fields.

It’s a war not only against the forest, but against everyone who lives in it: indigenous peoples, traditional communities, the inhabitants of the cities, towns and villages located in it. And because the war is destroying the world’s largest tropical forest, a vital barrier to global warming and rising temperatures, it is a war against the entire population of the planet.

On the battlefield, the roar of the flames and clouds of dense smoke are everywhere. Terrified animals and birds flee the fires, although many do not make it. Thousands die. Millions of insects perish. Brazil has up to 20 per cent of the planet’s biodiversity, but the war on the Amazon is steadily reducing it.

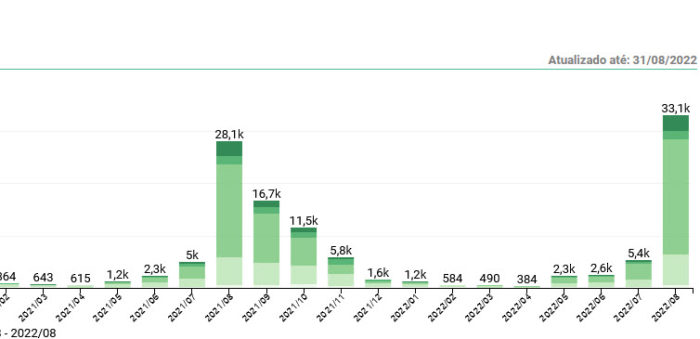

On one day alone, 22 August, a record 3,358 fires were registered in 24 hours by the government space research agency, INPE. In the month of August INPE detected over 33,000 fires, the highest number since 2010. The rainforest is humid, it does not catch fire spontaneously, as President Jair Bolsonaro has claimed. The fires are started deliberately after the forest has been cleared, to prepare the land for agriculture.

In the towns and cities of the Amazon basin, where over 20 million people live, hospitals and health posts are crowded with the victims of the war, many of them children and old people, red eyed and coughing, struggling to breathe, suffering from respiratory illnesses caused by the thick palls of smoke that hang over their homes.

The frontline in the war on the Amazon is now the region known as Amacro, the southern swathe of the rainforest which includes parts of three states, Amazonas, Acre and Rondônia, hence the acronym. Over a third of all the deforestation now takes place here, as land is illegally cleared for cattle pasture and maize and soy plantations.

The teeming forest is replaced with silent fields of pesticide-drenched soy tended by giant machines, grown to feed Chinese pigs. Or with vast herds of white zebu cattle, munching grass among the charred remains of the mighty trees that once stood here, destined for the meat counters in Brazilian and European supermarkets.

The Amazon is huge. It covers two thirds of Brazil and sizeable chunks of Bolivia, Peru, Colombia, Ecuador, Venezuela, Surinam, Guyana and French Guyana. But the relentless onslaught, unleashed by the government of Jair Bolsonaro in the four years since he took power, is clearing larger and larger areas. Satellite images show that deforestation is reaching into previously untouched areas where until recently the lack of roads protected the rainforest. The advance of roads, both legal and illegal, is changing that.

Roads of destruction

In any war, roads are vitally important. Traditionally the rivers of the Amazon were its roads. In the 1960s and 1970s the military dictatorship decided to drive roads 1000s of kms long through the region, to integrate what they saw as an empty region into the rest of the country. The roads enabled and spurred deforestation. Today roads are also being built, illegally, by loggers, miners, landgrabbers and landowners. A study carried out by the NGO Imazon discovered over 3 million kms of illegal roads, most of them running through conservation units, indigenous territories and state-owned forest areas. Many were recently opened. The government is also planning roads, resuscitating the 900 km long BR319 highway from the Amazon capital Manaus south to Porto Velho, and a 480 km extension of the existing BR163 highway north over the Amazon river to the border with Surinam. More roads, both legal and illegal, always mean more deforestation.

Where roads cannot be built, the invading army uses airplanes. IBAMA, the government environment agency discovered 277 illegal airstrips built inside and around the area of the Yanomami indigenous people. Every day there is a constant traffic of small planes and helicopters which fly men and supplies to the dozens of illegal mining camps that now infest the Yanomami area and return laden with the tons of gold being mined. Last year alone 86 small planes and helicopters and over 16,000 litres of fuel were confiscated by the environment agency. Once the garimpeiros were amateurs, digging away at the riverbanks with pickaxes and shovels, now they work for companies which use heavy machinery to destroy the riverbanks and expose the gold, while scores of dredges work the riverbeds.

War always destroys homes

These operations use mercury to separate the specks of gold, depositing the toxic element in the rivers where it contaminates the fish, one of the Yanomamis’ main food sources. The stagnant pools of water left by the mining become breeding grounds for malarial mosquitoes. The Yanomami, one of the last large indigenous groups to come into regular contact with the outside world, depend on the rainforest not only for food but as home to their spiritual world. None of that matters to the invaders, and they and many other indigenous peoples have become helpless victims of the war on the Amazon, watching their habitat destroyed by outsiders, just as Ukrainians, Yemenis, Syrians and Congolese have seen their homes being destroyed.

As always, war attracts all sorts of criminals looking for easy profits, and the war on the Amazon is no different. Besides the illegal loggers, miners and landgrabbers, criminal gangs have also seized the chance to enlarge their drug trafficking activities, as the presence of government agents, posts and bases is reduced, and federal authorities have given the green light to the war. Scientists are warning that the Amazon’s tipping point is getting near. The extreme climate events seen all over the world this year are dramatic warnings of what will happen if the world continues to warm. Brazil’s responsibility, as home to the largest tropical forest in the world, and therefore the largest absorber of carbon, is crystal clear. The only hope of a peace treaty in this war is a change of government. While the warmonger Bolsonaro remains in power there is no hope of saving the Amazon.