The women of Tz’ununya’ Collective have struggled for eight years to defend and conserve Lake Atitlán by pushing for local authorities to stop the deterioration of the lake. To do so, the organization has sought the help of a program run by the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights offering legal counsel for the defense of the rights of women and Indigenous peoples.

This article was originally published in Spanish by our partners at No Ficción and has been republished in English as part of our partnership for the Environmental Defenders series, curated and edited by Katie Jones and inspired by the Global Witness report highlighting the terrible toll of killings of those who seek to defend their rights to land, water, and their own way of life. Each new post is released initially to LAB ‘patrons’ (paying subscribers), but will later be made available in full to all visitors to LAB’s website.

Nancy González strolls along the beach of Lake Atitlán, or, as it is known in the Mayan language Tz’utujil, Qatee’ Ya’: ‘our mother lake.’ González, 32, grew up playing with her siblings along the shore of San Pedro La Laguna. ‘We believe that the lake is like our mother, because she provides food. It’s important for us to have a connection with the lake,’ she says as she recalls how 20 years ago the water was crystal-clear and the beach was solid. ‘We can’t deny that it is deteriorating, and we must work to stop the contamination,’ she asserts.

San Pedro La Laguna, a town of 12 thousand mostly Maya Tz’utujil residents, sits along the mountainous northern end of the Atitlán Basin. It is home to a group of defenders of the lake, most of them women. In 2009 they were the first to warn municipal and health authorities of the appearance of cyanobacteria, an algae that threatens to contaminate the potable water supply of the 13 towns living in the 130 square kilometers around this important lake.

González is the coordinator of the Tz’ununya’ Collective, a group of 12 committees of Mayan women representing the aldeas and sectors of San Pedro La Laguna. For a decade they have acquired the necessary skills to save the lake through litigation. They also organize so that municipal authorities take into account their voices and ideas about care for the water and ending the contamination, as well as the socialization and preservation of Tz’utujil culture.

The collective’s first legal battle is its opposition to the mega-project known as Mega-Recolector (“mega-collector”), a proposal made in 2013 by the Private Association of Friends of the Lake to install sub-aquatic tubes that its proponents say would collect the dirty water of each town and send it to a treatment plant to produce methane that would power three hydroelectric plants.

Unsure of the benefits of the proposal, the Tz’utujil population of San Pedro La Laguna rejected the project and opted to find its own solutions to the contamination of the lake, like the installation of biodigesters that are pending municipal approval. The women also remove solid waste from the banks of the lake every two weeks.

González says that in 2019, when Mega-Recolector reached the desk of the president of Guatemala, the women decided to file an injunction before the Constitutional Court (CC) due to the project’s lack of prior community consultation. They feared that the state would finance the installation of the tubes.

In 2022, the CC rejected the women’s petition, accepting the government’s claim that it was not promoting Mega-Recolector. González says that the rejection was not a defeat. ‘If we look at it in a binary way, we won, because we gained time and managed to stop the project’s approval at the departmental and national levels,’ she says. ‘We also issued a warning and increased the visibility of the complex problems of deterioration of the lake.’

The need to turn to legal mechanisms in the preservation of territory and rights is not exclusive to San Pedro La Laguna. In Guatemala many individual and collective rights of Indigenous peoples and women have yet to be recognized. In that context, the Maya Program of the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) created an initiative in 2009 to offer strategic litigation training.

How Does the Program Work?

The program began by advising the law departments of three universities: San Carlos (USAC), Mariano Gálvez (UMG), and Rafael Landívar (URL). In sessions held in person around the country, the first two cohorts trained 157 people: 47 representatives of Indigenous peoples’ organizations, 14 attorneys, 84 students, and 18 university professors.

Those first two phases allowed for the creation of a network of attorneys to work on 23 litigation projects devised by Indigenous organizations during the program.

The third cohort received virtual training with a focus on gender from the Division of Juridical and Social Science of the University Center of Western Guatemala (CUNOC) in Quetzaltenango. Seventeen Indigenous leaders, six attorneys, nine professors, and 33 CUNOC students attended. The academic phase ended on June 3, 2021.

CUNOC professor Hector González became the liaison between participants in the virtual campus. ‘It was enriching to give technological tools to Indigenous authorities working to defend their rights because the internet is also a right. They not only received training on strategic litigation, but also on technology that can benefit their work, from cameras to Google Drive.’

Tz’utujil leader Nancy González participated in the third cohort on behalf of the Tz’ununya’ Collective. By then this group of women had already spent years working on behalf of Atitlán Lake. Nancy said her participation in the OHCHR program was enriching: ‘It enhanced our capabilities,” she said. “For example, before we had a communications strategy that went hand-in-hand with our juridical and political work.’

The collective’s participation in the program led them to draft a proposal to regulate protections for the beach. One of the environmental challenges facing the lake is the extraction of sand for sale in the construction industry. The regulations call on the municipality of San Pedro La Laguna to prohibit this activity, given that the extraction of sand weakens the beach’s surface and complicates the contamination of solid waste. The regulations are under revision by the municipal council, which should make a decision in the first half of 2022, according to González.

A Change in Paradigm

As part of the third cohort of the Strategic Litigation Program, attorney Juana Lisseth De León, from Quetzaltenango, was assigned as legal counsel to the Tz’ununya’ Collective in drafting the regulations to protect the beach and prohibit the extraction of sand. ‘My experience in this course was highly enriching. I gained knowledge about human rights that during law school I did not have the opportunity to learn about,’ she says. ‘My learning about the needs and struggles of women changed my life. Now I want to focus my legal practice on women.’

Edwin De León Soto shares his opinion about the program. De León, a law student at CUNOC, was assigned as a member of the third cohort to advise ancestral authorities in Palajunoj Valley in Quetzaltenango in the drafting of legal arguments in filing an injunction against the continued use of a garbage dump in their community. ‘As a law student this program allowed me to identify the state’s shortcomings in terms of the rights of Indigenous peoples. While the program has ended, I’ve stayed on as assistant attorney with the K’iche’ Indigeous authorities in the valley,’ he says.

This is one of the main objectives of the strategic litigation training: empowering Indigenous peoples in their courtroom struggles. It is what is also happening in San Pedro La Laguna, 100 kilometers from Quetzaltenango. ‘What’s most relevant is that all women have access to tools to defend territory and water,’ says Nancy González, ‘because only then can we make the state work on behalf of the people.’

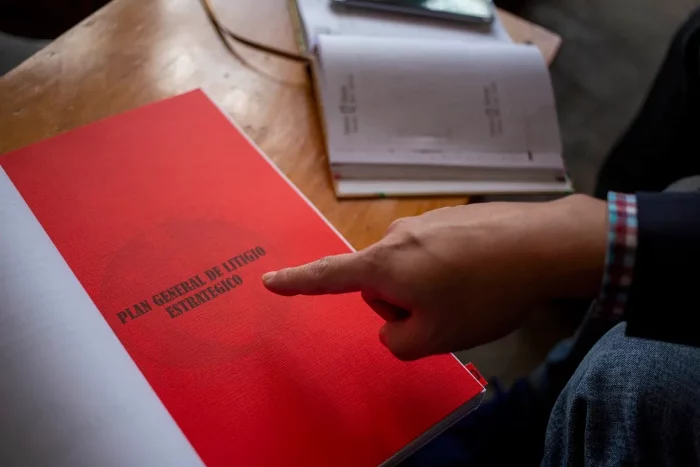

In Quetzaltenango, Julio Cesar Pérez Caguex (left), civil society representative, and Edwin De León (right), CUNOC law student, review the gender-focused strategic litigation plan in defence of Indigenous peoples. Photo Oliver de Ros.