The arrival of Covid-19 in Latin America devastated the region. Simultaneous health, economic, and humanitarian crises and catastrophic loss marked communities across Latin America, as policies failed them. The pandemic exacerbated pre-existing issues in the region such as gender-based violence, violations of Indigenous rights, and unequal access to information and education. Despite the adversities, the Coronavirus pandemic has also shown the strength and determination of communities struggling for a fairer society. Across the region, there are calls to build a more just economy and society than the one that was left behind.

This is a virtual chapter of LAB’s book ‘Voices of Latin America’. The full text was first available to LAB’s Patreon subscribers and is now available to all LAB readers. On the Voices book website you can also find articles, videos, and information about LAB events linked to this chapter.

Voz brings our loyal subscribers a long-read article each quarter, conveying the experience and analysis of our partners: activists, journalists, artists and academics. We hope that their in-depth testimony and commentary will help broaden our understanding of Latin America, and through it, the world.

“The pandemic has been a clear reflection of the inequalities in this world. If we had a vague idea of inequality beforehand, by now the pandemic has exposed us to its full reality. We’re able to see who the most and least important people are nowadays: who are the invisible ones that nobody cares about.

Onésima Lienqueo, Mapuche educator, Chile.

The first case of Coronavirus in Latin America was officially registered in São Paulo, Brazil on 26 February, 2020. Cases were confirmed across the region over the following few days. Since then, given the region’s poor health infrastructure, the reliance of some communities’ economies and livelihoods on tourism, and political instability, the situation has escalated into simultaneous health, economic, and humanitarian crises. The region experienced catastrophic loss. Images of coffins on the streets of Guayaquil, Ecuador, made global headlines; Peru saw the most Covid-19 related deaths per 100,000 people in the world; and misinformation, minimalization, or denial about Covid became notorious in Brazil, Nicaragua, and Mexico.

The health emergency provided an excuse for increased authoritarianism in some areas of Latin America. In Colombia, Covid-19 monitoring apps threatened the rights and privacy of the most vulnerable, and violations of isolation rules led to harassment, abuse, or violence at the hands of the police. Meanwhile in El Salvador, draconian measures introduced a 30-day detention for anyone breaking the lockdown and there were reports of arbitrary arrests with excessive force. Where the Government did not enforce the lockdown, some armed groups and militias threatened anyone who left their home with baseball bats or guns.

As the virus spread, concerns grew for Latin America’s vulnerable communities. Indigenous peoples, who have historically been decimated by diseases such as measles and who face systematic discrimination, lacked the resources to confront the pandemic. The land-grabbing and invasions of their territories did not halt as the world stopped, but the invaders now brought the second threat of a potentially fatal disease. In a region in which around a quarter of women have experienced intimate-partner violence, quarantines left many women trapped indoors with potentially violent partners and relatives. Trans communities in Panamá, Colombia, and Peru found themselves unable to leave home due to gender-based restrictions. Migrants were forced to return to their homelands after losing work and their homes, while others became migrants, desperately fleeing unliveable situations. With schools closed, and many families lacking access to the internet and internet-enabled devices, Latin American children lost on average almost a year’s education. Across the region some 4.7 million people formerly regarded as middle class slid into poverty, a number only slightly reduced by social transfer programs such as Auxílio Brasil.

Despite the adversities, the Coronavirus pandemic has also shown the strength and determination of communities struggling for a more just society. Many of the issues they faced did not originate with the pandemic. They are long-term, deeply complex and often intersectional problems. Nonetheless, as the pandemic exacerbated many of those issues to catastrophic levels and brought others to the forefront, social leaders were determined to protect and provide for their communities.

Indigenous survival: ‘the invisible ones’

For many of the region’s Indigenous communities, the arrival of the pandemic in Latin America recalled the decimation of Indigenous groups by diseases such as measles, flu, and chickenpox, historically carried into their lands by European explorers and conquistadores. Today, Indigenous lands and health are threatened by invading miners, famers, and foresters, both artisanal and big business, as well as evangelical missionaries. Systemic inequalities make Indigenous communities more vulnerable to the pandemic in other ways, including higher rates of overcrowding and greatly reduced access to sanitation, healthcare and water. Meanwhile, pandemic-related mobility restrictions limited remote communities’ access to markets, to sell produce and to buy food, and curtailed freedom of movement for communities that straddle national boundaries.

In the absence of governmental protections, many Indigenous communities implemented their own measures to protect themselves from the pandemic, including monitoring and data collection, information campaigns, health cordons, restricted access to and movement within communities, isolation and traditional medicines. These measures were essential. For many Indigenous communities, the threat of Covid-19 meant not only the potential loss of loved ones, but also the loss of languages, traditions, and ancestral knowledge. As the disease affected older people more severely, communities lost elders and their memories: libraries of knowledge of how the moon affects crops, when the rain will come, the meanings behind traditional dances, and the preparation of medicines and foods. Younger generations have rushed to record this knowledge before it is lost forever.

Colombia

In Provincial in the La Guajira region of Colombia, the arrival of the pandemic was in some ways a blessing, because it meant that work at Cerrejón, the vast coal mine which borders Wayúu territory, was suspended. Marcos Angel Brito Uriana, a community leader, activist, and social communicator from the Wayúu community explains:

‘It’s quite ironic what has happened in Provincial, actually, because to a certain extent the pandemic helped us. It hasn’t affected our inhabitants – thank God – and we haven’t had a Covid death in the territory. We’ve had very few deaths because we practice traditional medicine, and this has helped combat Covid-19 in the Wayúu community. But elsewhere in La Guajira, among the Alijunas and westerners – those who aren’t Wayúu – obviously there’s been a big impact.

‘Why do I say it’s ironic? Because at the start of the year, when the pandemic began, all companies were ordered to stop [production]. And the company [Cerrejón] stopped thanks to the pandemic and also thanks to the efforts of a labour union. The company stopped for eight months, and that helps us by reducing levels of pollution and contamination in the community. During that time, we could breathe clean air. How does that help us? Because while the company isn’t functioning, the possibility of pollution making us sick is minimal. Therefore, we’re not going to hospital appointments or doing anything outside of the community, so that helps us to reduce the possibility of contagion by Covid-19. So, in that way Covid has actually worked in our favour in the community, because it stops the company, allows us to breathe clean air and sleep soundly because there’s no noise or vibrations… So, if you will, we’re seeing the good side of Covid.’

However, the benefit was limited. The pandemic also forced the community to change their traditions, and restrictions meant a loss of income, as Marcos explains:

‘But obviously it goes without saying that it has had a huge impact because, like everyone else, it’s forced us to adapt, to use means of communication, for example, to break with our customs and implement new ones. In the Wayúu community, for instance, it is very important to gather together around bonfires and share stories, tales, and myths and transmit traditions orally from generation to generation. So Covid has had an impact in that sense [because we can’t gather as we did before]… Thank God we haven’t lost a single loved one because of Covid but it has impacted us because, obviously, we can’t go out like we used to, we can’t do the same things we did before to generate income in the community…

‘For example, the commercialization of the products we make… We can’t sell agricultural products like we used to. Before, people went out and sold those products and now they can’t do it. There are also people, for example, who have small businesses like restaurants which have had to close because of the pandemic. And these are economic activities which allow people in the community to be self-sustaining. For example, going out and selling the bags they make in the community, which is part of traditional Wayúu craftmanship, can’t be done anymore. Now they have to start to commercialize the bags, to find strategies to sell them via social media.

‘We Wayúu don’t have a great grasp of technology, so we’ve had to adapt to that, acquire that knowledge. We have our own traditions and it’s very difficult because we are, as I said, in a rural area and we don’t have access to all the new technology with which we can commercialize our products. So, for example, the sale of yucca, corn, beans, all the things we plant and which we used to go out to sell to people as street vendors or on the roadside, we can’t do that anymore. The eggs from the hens we have here, we can’t sell those either. All these kinds of things we can’t do because of the pandemic. That forces us to look for alternatives and obviously we’re limited because what other alternatives can we pursue to generate income? People who work at the company can guarantee food for their family, but the commercialization of mutton or lamb is something we have had to stop doing.’

Brazil

The experience of Marcos’s community was not the norm and many Indigenous communities continued to be adversely affected by mining. While many industries shut down due to Covid-19 restrictions, legal mining continued, deemed a ‘strategic sector’. The increase in the price of gold and loss of work also accelerated illegal mining on Indigenous lands. In ‘normal’ times, illegal mining contaminates water supplies and sometimes threatens the lives of those defending their land. During the pandemic, the possibility of locals contracting Covid-19 was added to the list. The death of a Yanomami teenager, aged 15, due to Covid-19 provoked an outcry and calls to the authorities to take immediate action against illegal miners. The boy was from the Uraricoera region, an area on the Venezuela-Brazil border known for artisanal mining.

In Brazil, with the Bolsonaro government’s racist rhetoric against Indigenous peoples, there was little acknowledgement of the need for special measures to protect them against the pandemic. Many communities took the decision to shut themselves off, closing the entrance to their lands, to protect themselves from the virus. Nonetheless, according to the Association of the Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (Articulação dos Povos Indígenas do Brasil – APIB), government agents carried the virus to four communities in northern Brazil. In eastern Brazil, Indigenous people in urban settings have avoided hospitals and vaccination centres due to the racial discrimination they experience there.

Elder Juarez Munduruku, from Pará in northern Brazil, describes the struggles he and his community have faced during the Bolsonaro administration and how illegal logging presented another threat during the pandemic:

‘We are facing a huge battle now. Our struggles have increased. We worry under this current government because it doesn’t listen to us. This government doesn’t support the interests of the Indigenous people… Since Bolsonaro stepped into power, we have not set foot in Brasilia. Fighting [for our rights] has become more difficult for us. This is why things have worsened. Then this pandemic arrived. We can’t go anywhere. And here in the middle of Tapajós everything has multiplied. Invasions and forest harvesting have increased. And we can’t react. We can’t go to the loggers and say “This here is ours. You can’t extract. You can’t be here.” At any moment, the logger will kill us for being in our own territory. If we ask him to leave, it is because it is ours. But he doesn’t recognize this. They think that it is us who is stealing something that is theirs. They kill us for something that is ours…

‘Since the arrival of the pandemic, we all isolated ourselves as requested by the local state governments… The loggers and the miners are not respecting this. The loggers themselves bring the virus into the village. They enter the village invading the territory… and all of a sudden, those people spread the virus to us. The same can be said for the mining prospectors. They are not respecting this government protocol at all.’

The Munduruku people used their knowledge of traditional medicine to defend themselves against the arrival of the pandemic:

‘When [the virus] started spreading, we, the Munduruku people, started to prepare ourselves… So, we gathered the leaders of the Middle Tapajós. We had a meeting here in Sawré Muybu about the pandemic. Then there was a case in Sāo Paulo… We sat down with the leaders and with the elders that have more knowledge than us. I see them as our teachers because it’s from them that we learn about a lot of things. For example, it was from them that I learned about medicine derived from the forest. They said that we have traditional rainforest medicine, a medicine that we are going to take to fight the pandemic. So, we sat down with the teacher. The students and everyone. The elders taught the children about the types of roots and the types of cures for inflammation. We, the leaders, also accompanied them.’

Thankfully, Juarez’s community survived.

‘We began making medicine and taking it before the virus came. We already knew that it was near. It started in the Amazon and then it got here. And that’s how it came. When it came, we didn’t realize that we were infected with the coronavirus. We caught the coronavirus as if it was a cold. Thank God that not even one person ended up dying because of it. The people that we lost were those people who were hospitalized in Jacarepaguá and Sāo Paulo. We lost those people.

‘But we didn’t lose the people that we looked after inside the village. We have medicine to prevent it. But these days we know that there is a vaccine, which will weaken the impact of the pandemic. We didn’t make a medicine that will cure the virus at once. Instead, it prevents it. So, then the coronavirus spread throughout the village. Everyone caught it but nobody ended up using the equipment that was donated to us by our partners. We didn’t use it because we didn’t have one severe patient to use this equipment on… Not one person died in the village.’

Chile

In Chile, the arrival of the pandemic brought with it a new stage in the ongoing conflict between the Mapuche people and the Chilean state. Onésima Lienqueo is Mapuche, living in the Araucanía region in Chile. She is an educational psychologist, teacher, and human rights defender, working mainly for the rights of Indigenous children. Onésima is one of the founders of La Red x la Infancia Mapuche (Network for Mapuche Childhood). She describes how the authorities threatened and failed her community during the pandemic:

‘Authorities have turned a blind eye to the pandemic. I think even as the region with the highest number of Covid cases in Chile, we’ve seen more repression than access to healthcare and prevention of coronavirus cases. I point this out because in Chile we’re divided. In other parts of Chile, the police are out keeping the pandemic under control. In the south of Chile – in Araucanía and Biobío – the police are not controlling Covid. Instead, they’re repressing the Mapuche people and communities in our territory. They don’t comply with health protocols. In reality, the accusations, attacks, and paramilitary force are acts of terrorism. It’s as if we were living in two separate worlds. We’ve got illness, Covid, the pandemic, and infections. But it’s only given rise to more repression and militarization.

‘This is also down to how many natural resources there are in the territory and the economic interests of business. What we see in the news here is that a forest or a school has burnt down, or that there was an attack last night by a group of Carabineros en Lleu Lleu. This is the breaking news in Wallmapu [Mapuche territory] – not Covid. We’ve been totally abandoned in that sense.

There’s the vaccination programme, for example, for which Chile has been noted for its success. But the vaccines haven’t reached the Indigenous communities.[1] There’s been no way to vaccinate the elderly here. So, in the end it’s all biased and we’ve been cast off as if we didn’t exist. It’s like, we’re not a part of the state, so they won’t make it easy for us. They give us militarization, the police, and security, but they don’t develop our education or healthcare. That’s the reality of life in Araucanía, which is different from the rest of Chile.’

All but four countries (Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru) in the region failed to collect data on Covid cases, deaths, and vaccination rates disaggregated for Indigenous peoples, making it difficult to understand the true impact of the pandemic on them.[2] In Chile, the Ministry of Health did not initially implement measures for Indigenous communities in its Coronavirus Action Plan and only released recommendations for Covid-19 prevention and promotion of health protocols for the Indigenous population in September 2020, six months after the arrival of the disease in Chile.

For Onésima, this was too little too late:

‘The pandemic has been a clear reflection of the inequalities in this world. If we had a vague idea of inequality beforehand, by now the pandemic has exposed us to its full reality. We’re able to see who the most and least important people are nowadays: who are the invisible ones that nobody cares about. In the latter, we see the Indigenous people.’

Locked in with their abusers

“The violence was already there, Covid simply exacerbated it”

Sofía Lozano Snively, Alternativas Pacíficas, México.

A major concern at the beginning of the pandemic was how restrictions on movement would impact women living in situations of violence. In Latin America, it is estimated that one in ten women have experienced sexual violence from a partner. While lockdowns were necessary for public health, for women who experience physical, sexual, or psychological violence from their partner or other members of their families, quarantines did not mean safety.

In the early days of the pandemic, Brazil’s Ligue 180 domestic violence hotline received 18 per cent more calls in the first 10 days of the pandemic than in the previous two weeks. Colombia’s hotline received four times as many calls than usual during the first week of lockdown. In Argentina, the average number of daily calls made to the 144 helpline for gender-based violence (GBV) increased by 27 per cent.[3] Despite the increase in the number of calls for help, the number of official complaints did not increase in parallel, leaving women at risk and without justice.

The Argentine government had been proactive in tackling gender-based violence since the approval of the 2009 National Law 26,485 for the Integral Protection of Women, which took a more comprehensive approach. In anticipation of the potential rise in GBV, the Ministry of Women, Genders, and Diversity enacted a series of emergency measures to create a gendered response to the pandemic. These included declaring the 144 helpline an essential service, expanding the hotline’s capacity by hiring more staff and improving its technology, introducing a WhatsApp channel for people unable to call the hotline, and providing shelter at hotels and other accommodation for people in situations of extreme violence.

Elsewhere however, there was a conspicuous lack of action. Legislation in Haiti and Cuba does not consider gender-based violence, leaving women with no recourse to state support or justice. In Mexico, the government continued to dismiss the issue of violence against women. President Andrés Manuel Lopez Obrador publicly denied any increase of GBV during the pandemic. Mexican authorities are obliged, under current legislation, to stop violence to guarantee victims’ integrity; to prevent any further harm to the victim; and critically, to ensure a safe space such as a shelter for victims. Yet 15 out of the 32 state judiciaries did not provide protection for victims in their emergency health lockdown plan.

Across Mexico, April 2020 saw a 42 per cent increase in emergency calls relating to violence against women compared to April 2019, the highest number since 2016. In Mexico City, the number of calls made to Línea Mujeres increased by 97 per cent in May 2020 compared to the same month the previous year. AMLO, however, declared in a press conference that ‘90 per cent of these calls were fake’, contradicting official statistics, which include only calls deemed genuine by the Government itself.

Similarly, the number of new criminal investigations into family violence in Mexico was the largest since the crime was first registered five years earlier. April 2020 saw the number of women murdered increase by two per cent on March, compared to a slight decrease in murders of men.

Sofía Lozano Snively works at Alternativas Pacíficas, a women’s shelter in Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico. She explains how the arrival of the pandemic exacerbated violence against women:

‘We say that there are many factors that facilitate violence. For instance, here it’s very hot so some say “oh, it’s the heat that leads to violence.” I think that is a discourse that was replicated during the pandemic: that Covid caused the violence. But no, it was this quarantine, these restricted mobility policies, this obligation to be confined to a particular place without being able to leave that turned into another enabling factor. The violence was already there, Covid simply exacerbated it because of this situation of being in the same space together for longer. What we saw is that the number of emergency calls skyrocketed in all of Mexico. In Nuevo León and Alternativas Pacíficas we saw it like that – more women asking for help on these emergency helplines.

‘Those [first months] months we saw few women entering refugee centres… The pandemic arrived in March and April with the first “Stay at Home” order, and everything went downhill. As the months went by, around May, June, July when spaces began to open up, that’s when we saw more women coming forward. That’s when we noticed an unusual number of attempted femicides during that lockdown. Women that were almost killed. I think that the quarantine enables that – not knowing how to manage emotions, the stress caused by economic conditions, free time, the aggressor drinking more and taking drugs. All of those things put certain women at risk. In four months, there were 116 attempted femicides in Nuevo León. That is an alarming statistic, because if 19 women were victims of femicide in those four months, 116 women were in that risky situation. And those are the ones we know about.’

Alternativas Pacíficas never stopped providing support. Five of their seven Violet Doors – a network of safe spaces around Nuevo León – remained open throughout the pandemic. While figures show the increase of cases of domestic violence, fewer women were able to access help, safety, and support, as Sofía explains:

‘The clear message of “Stay at Home” played against us as an organization because fewer women stopped physically seeking help. Few continued with their therapy. Few came for the first time to seek help because the situation was complicated. They are women who are mothers, the ones who look after the home, they have more tasks to do and less time to themselves. I think this was something very negative that forced us to seek alternatives so that we could continue providing our support without neglecting them, knowing that these women were in risky situations in their homes. We had to start providing support at a distance, principally by phone, and here is when another obstacle arose. There were women that felt comfortable having their psychological therapy or follow-ups on the phone, but there were women who didn’t because they were much closer to their aggressor. They were being monitored, and many women don’t tell their partner they’re receiving psychological therapy. Many have not yet managed or have not wanted to separate themselves from the aggressor. They didn’t feel comfortable having this support. That worried us. How can we be there for women when they are so isolated from us and from society?’

CAMI Zihuakali is another women’s refuge in Nuevo León. It provides services and shelter for Indigenous women, who regularly face discrimination and an absence of services available in their languages. Isabel Muñiz, head of administration and coordination at CAMI Zihuakali, spoke about the refuge’s determination to remain open:

‘Lockdown led to this new way of coexistence that many Mexican traditional families were not used to. There was an explosion of violence because there’s a very important factor in Mexico… Often, men tried to deal with lockdown with alcohol, and that triggered violence… The way families were living became very different during the lockdown. That represented a big challenge for us. We decided not to close, we were one of the few organizations that decided not to. For example, in previous years, we would accompany 15-20 women. Last year we had more than 50 cases requiring legal action, and 45 cases of psychological and emotional tension.

‘We provided our support in-person with all social distancing measures in place. We tried to do it digitally but the women weren’t comfortable. They said they preferred to see us in person even if they faced risks when going out… All the other institutions where women should be receiving attention because of their geographical locations were closed or working virtually or by phone. We, in this case, decided to keep the house open. That for us was the main tool we had, to keep the house open alongside our presence and support for women.

‘We had users who had Covid but we couldn’t deny our services to them… We had a taxi service that would not refuse the service even if they knew they were transporting a person with Covid. We tried to be available 24/7, which was very important for the women.’

In 2020, at least 4,091 women were victims of femicide in Latin America and the Caribbean. Surprisingly, this marks an apparent decrease of about 10 per cent compared to 2019 – it may reflect lower reporting because the work of monitoring agencies themselves was restricted by the pandemic. Also, during lockdown most violence took place within the home and with less likelihood of other witnesses being present. Data regarding other forms of violence against women is far more ambiguous, for reasons including a lack of formal reporting and varying definitions. The accounts of Sofía and Isabel show the importance of their services in providing support for women in situations of violence during the pandemic.

In the long term, the pandemic has set back gender equality across the region. Women took on a larger burden of unpaid work, including taking care of the home, and raising and educating children while schools were closed. Furthermore, women were more impacted by the economic consequences of the pandemic, as they occupy a greater proportion of the informal economy and hold more jobs in sectors most affected by restrictions, such as food and accommodation services. Increased sexual violence against girls will leave more out of education if they become mothers. Meanwhile women across the region were less able to access healthcare, including sexual and reproductive health services, and it is estimated that the increase in home births may have led to higher maternal mortality rates.

Gender-based violence and machismo is the pandemic that preceded and will unfortunately succeed Covid. Sofía believes there is a lot more to be done to create a more holistic approach to ending gender-based violence:

‘You need a more holistic vision. Women not only need to file a complaint so [the aggressor] can go to jail –if he goes to jail–, we need to have tools to be able to leave these situations of inequality. I think that economic empowerment of women who face violence has not been made a priority in the governmental agenda… I think we have to work with the aggressors… I don’t see any programs of male re-education. [Nor do we] work with children. We talk a lot about equality, but how much really are we changing at the childhood stage? These roles and stereotypes are still being reproduced in schools and in families, where we learn everything. We need to question this machista culture in which we live, and which we are trying to survive every day.’

Gendered lockdowns

“It was, in short, hell.”

Lu Gilberto de la Rosa, Co-founder of Hombres Trans Feministas

Gender-based violence was not only limited to women. Legislative simplification of GBV as violence against women excludes the LGBT+ community and therefore the attacks on that community are not included in the data. During the pandemic, however, the trans community in particular reported attacks by security forces as well as discrimination in the street or supermarkets during quarantines, especially where the restrictions were determined by sex.

According to a 2020 report, Latin America and the Caribbean has some of the highest number of cases of rape of trans people and transfemicides (the murder of a trans woman). No country in the region has a specific law for transvesticide or transfemicide, and only Argentina has published guidelines for the recording of statistics on these crimes.

Yet, during the pandemic, trans people were disregarded by the law in another way. In Panama, Peru, and Bogotá (Colombia), ‘pico y género’ lockdown policies determined by sex the days one was permitted to leave the house. The aim was to reduce the number of people going out of doors, and therefore reduce transmission rates.

For example, in Panama, ‘women’ could leave their homes on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, to go to the supermarket, pharmacy, or run errands; ‘men’ could do the same on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays. The policy was introduced under a cis and binary understanding of sex and based on the sex marker on the Panamanian identity card, which shows the sex assigned at birth. Juan Pinto, Minister for Public Security, stated that the measure was ‘for nothing more than to save your life’. However, trans groups and international human rights organizations immediately criticized the measures for their disregard of trans and non-binary people’s lives.

Lu Gilberto de la Rosa is a writer, artist, and activist from Panama. He is also a trans man who exudes optimism and whose two main principles are feminism and love. He co-founded the group Hombres Trans Feministas based on his belief that men need to be involved in the fight for gender equality and the need to create what he describes as a ‘more conscious, more colourful, nicer, healthier masculinity.’ The group also supports its members through the difficulties they face as trans men in Panama, both emotional (processing the trauma of being outcast from their family, for example) and pragmatic (for example, changing the name shown on their identity card). The group has grown from its three original members to 60 to 80 men seeking the kinds of support that became even more vital during the pandemic. Lu recounts his reaction to the ‘pico y género’ policy:

‘[W]hen that news was released, I felt very sad because I knew the implications that this was going to have on the lives of many people. Fortunately, I have the support of my girlfriend… She was the one who went out to buy medicine, to buy food and all that. But I had been sentenced to a prison. We live in an apartment in the city. I couldn’t even go out to sunbathe. It made me practically blend in with the bed. I was completely depressed for three months. I did not know what to do. You need to move. You need the sun… The Government said that it was to control the number of people, the movements of people who were going to be on the street. The truth is, it seemed crazy to me because it did not control anything. The cases continued to rise because there was a mismanagement of resources. It’s the corruption in Panama that is killing us… Speaking with my other trans friends and colleagues, they had the same feeling: the frustration that our rights were going to be violated by the Panamanian state again.’

Reports emerged from Peru, Bogotá, and Panama of horrific examples of abuse and violence against trans people during the ‘pico y género’ policy. One video which circulated on Twitter showed three trans women forced by Peruvian police to squat with their arms outstretched and say ‘I want to be a man’. In Panama, a trans woman was detained by the police for three hours for breaching the lockdown rules before being fined US$50. She had gone out on the day designated for women. Lu describes the difficulties he faced:

‘If there was a trans partner who needed to go out, a witch hunt began. Because on my identity card my sex is F, female, well that was the day that I had to go out. For many trans men with a masculine appearance, going out on that day caused a lot of trouble in the places where we went to look for food, injections, or medicines, because they did not allow us in on the day designated for that ID. Security staff in the supermarkets said that this was going to confuse people and that we had to go out on the day assigned to men, like our appearance. But what happened when we went on the day assigned to men and they checked the gender on our identity card? Then also they wouldn’t let you in. There was a lot of trouble. Many trans women especially – because they take more risks and they are more empowered – were dragged out and mocked, which was the most degrading thing. When they yell at you and expose your private life in a queue where 200, 300 people are waiting to buy food, that’s terrible. There was a lot of violence on the part of the police and the supermarket security staff.

‘It was very frustrating, very difficult…. It is illogical to lock up a person because of their sex, because of their identity. It is a terrible violation of the rights and freedoms of human beings. It was, in short, hell, what trans people went through, with this restriction of movement based on gender.’

Unable to go outside, Lu fell into a deep depression. He found refuge in art and literature:

‘It was very easy for me to understand that what was happening to me was a very deep depression. I took a lot of refuge in reading: in reading a couple of feminist writers’ work and another couple of wonderful writers that I found out there. And I started to write. I said, well, this is my opportunity to make them listen to me, so people around me know what we were going through. With all the things that my friends and colleagues were telling me, I began to write. I began to create a little empathy in the minds of the people who read my posts on social networks. Of course, if people don’t know what’s going on, they don’t understand.’

Despite the difficulties he has faced, from being arrested for a kiss he shared with his girlfriend in public to being rejected by his family, Lu maintains an admirable mindset. He uses those setbacks to feed his determination to make the world a better place for everyone. As he said himself,

‘You know what, I am Lu Gilberto, I am a trans man and I am proud of who I am. From my resistance and from my writing and from my activism, we can change the world, we can improve this world. That is what I believe: with feminism in one hand and love in the other, we can, of course, change the world.’

In Peru, the ‘pico y género’ policy lasted only eight days although not because of any concerns about discrimination. Instead, it was because gender norms meant women did most of the shopping and therefore the streets remained crowded on those days. Likewise in Bogotá, the measure lasted four weeks before it was lifted due to changes in national regulations. Mayor Claudia López declared the measure ‘very successful’ – a judgement based on questionable statistics. In Panama, the ‘pico y género’ policy was enforced each time the country entered a new lockdown. Only in February 2021, almost a year after the beginning of the Pandemic and after several lockdowns, did the Government abandon the gender-based approach.

Misinformation and disinformation

Globally, mis- and dis-information has been a major barrier to countering the pandemic, with some research suggesting that it led to more infections and deaths. In Latin America, the Covid information battleground was also used for political gain and control.

In the early days of the pandemic, Daniel Ortega, President of Nicaragua, described stay-at-home measures as extreme and even encouraged mass gatherings. He claimed the virus was ‘a sign from God’ against militarism and hegemony: to show how transnational forces wanted to take over the world but that the United States ‘isn’t able to provide for its own citizens’. Even as late as the end of 2021, international organizations including the Interamerican Commission for Human Rights expressed alarm at the lack of information provided by the Nicaraguan Government relating to the pandemic.

In Venezuela, journalists were threatened, harassed, or even detained for reporting about Coronavirus. Their reports questioned the official case and death figures, which were dubiously low given the parlous state of the country’s healthcare system and other basic infrastructure, and the lack of beds for Covid-19 patients. In the first two months of the pandemic, attacks on freedom of information more than doubled compared to the previous two months.

Brazil’s experience of Covid-19 quickly drew international attention. Jair Bolsonaro, the populist far-right president, set the tone of his approach to the pandemic when he described the virus as ‘a little flu’. Despite himself catching the disease and suffering from a chronic lung infection afterwards, the president continuously denied the severity of the virus and consequently refused to take measures to limit its spread. Bolsonaro and his allies pushed hydroxychloroquine, a medicine used to treat malaria, as a cure for Covid-19 despite scientific evidence demonstrating that it was not effective and could cause adverse effects. The president’s attitude contributed to dangerous levels of misinformation and a fatal lack of measures and supplies to deal with the pandemic.

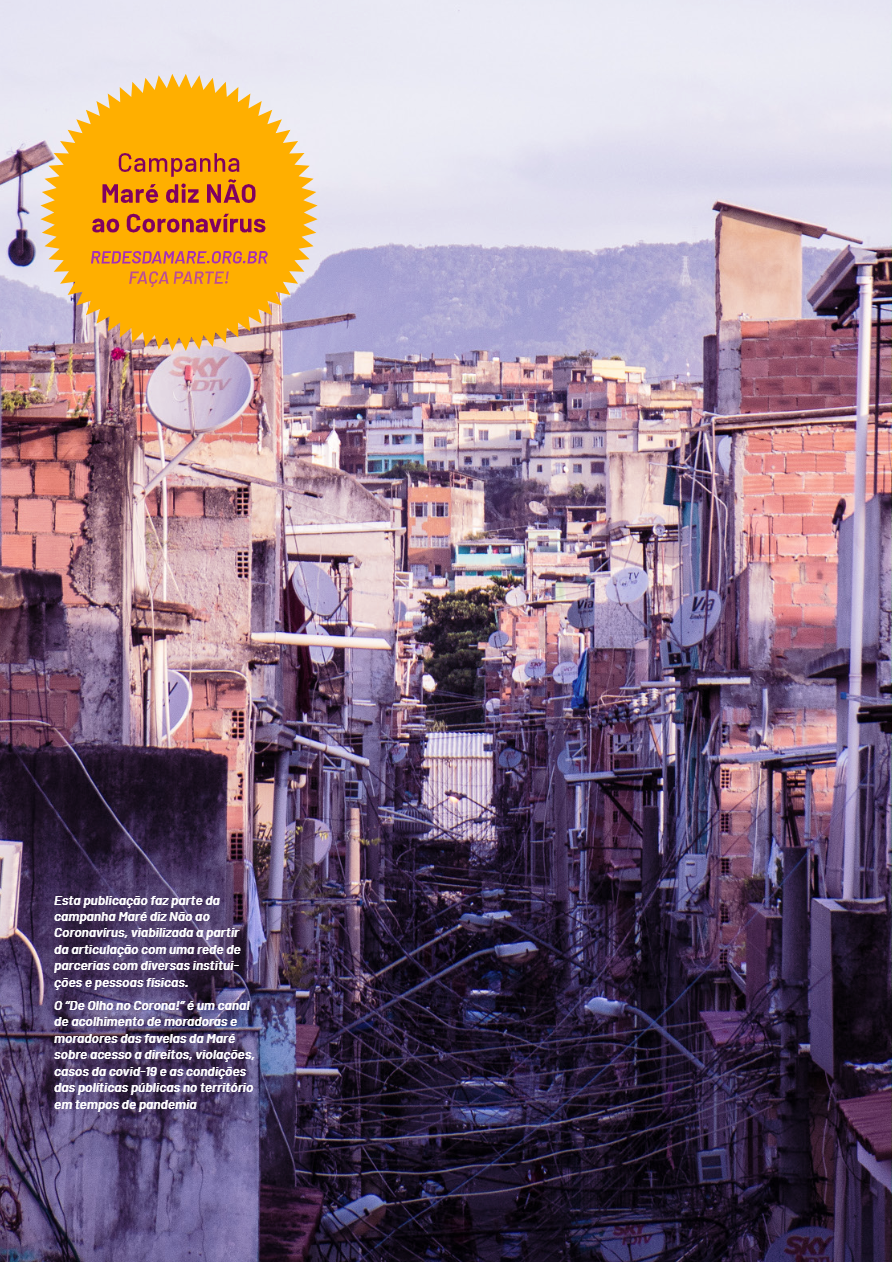

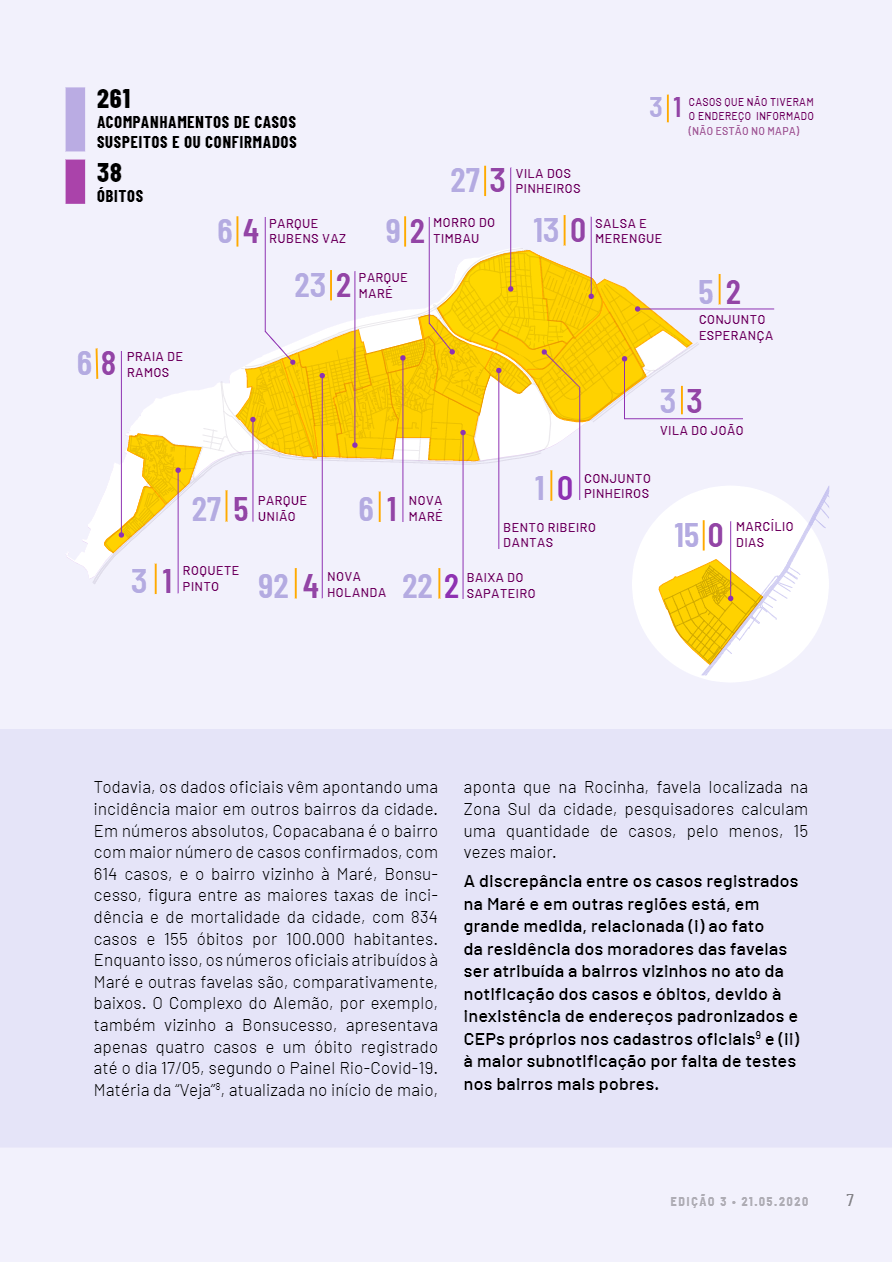

In the Maré favela, Rio de Janeiro, a group of young people gathered to tackle the misinformation. Data Labe was founded in 2016 in response to the propaganda during the presidential election. They use data to produce reports and to monitor their community. During the pandemic, they stopped going to their galpinho (a small shed) and began to work from home. Despite the challenges of not having space to work and weak internet connections, Data Labe’s outputs boomed.

Paulo ‘Polinho’ Mota Medeiros Junior is the Data Coordinator at Data Labe. He explains what happened at the beginning of the pandemic:

‘I guess [the boom] is because we work in communications, and in Brazil the political sphere works hard to spread misinformation. At first, there was a lack of data transparency, which was totally intentional, and people tried to hide the severity of things. In addition to that, we faced widespread misinformation. It had a huge impact on us when we heard some political actors talk about misinformation. We thought, “Dude, we need to develop a platform for that”. So, we tried to address what wasn’t being addressed. Newspapers and the mainstream media already discuss the impacts of Covid, its fatalities, right? But we started addressing other things as well: How do people have fun nowadays, how should we spend our time at home? An online funk gig maybe? What’s going on with food distribution in poor neighbourhoods? How are the youth from poor areas of Manaus coping with challenges? And so on.’

Beyond the disinformation and misinformation produced by authorities, there was also a lack of information on the extent of the pandemic within the favela too. Polinho explains why, and what they did about it:

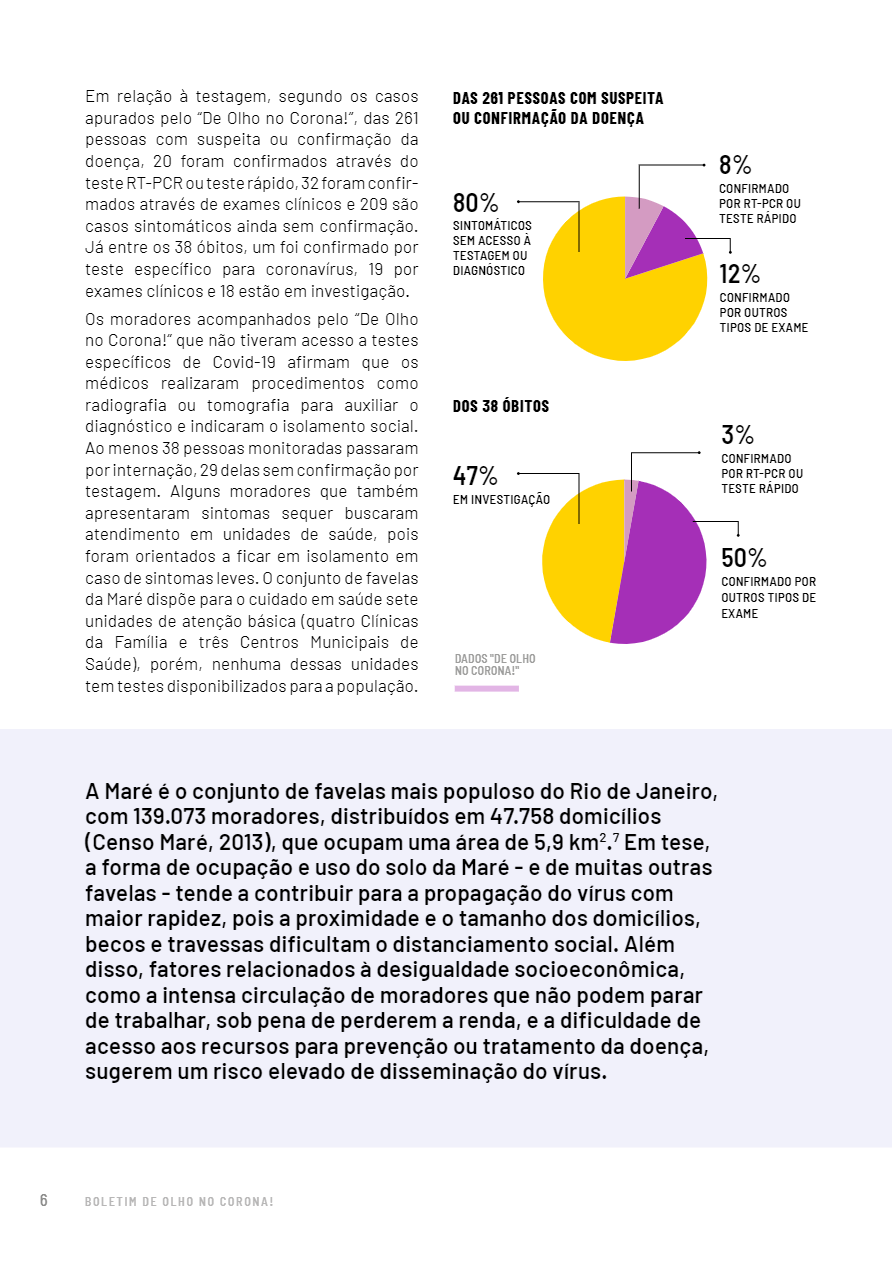

‘Something very important to us when it came to Covid and dealing with it was participating it projects by other organizations that were handling Covid data. There were two main initiatives: one was “De olho no Corona” (‘Watch out for Corona’) from Redes da Maré, and the other was the Covid-19 in Favelas Unified Panel. There’s also a monitoring programme called CocôZap (PoopZap), which deals with matters related to basic sanitation in the Maré favela. These are initiatives we could have done ourselves with our expertise, but we figured it was great that people were already doing it. So instead, we thought we’d help out with that was already going on.

‘We chose the “De olho no Corona” initiative and helped program their platform. It includes a form to monitor who got the virus, who did not, whether they tested positive, when it caused death, and which community they are from. It’s rare for city authorities to go into these communities. We are fully aware of the political bias that means they simply choose not to care. We helped the group at Redes da Maré carrying out “De olho no corona”, and made it something really useful by making a programmable database where all the information could be uploaded. As for the Covid-19 in Favelas Unified Panel team, we helped them build something similar.‘

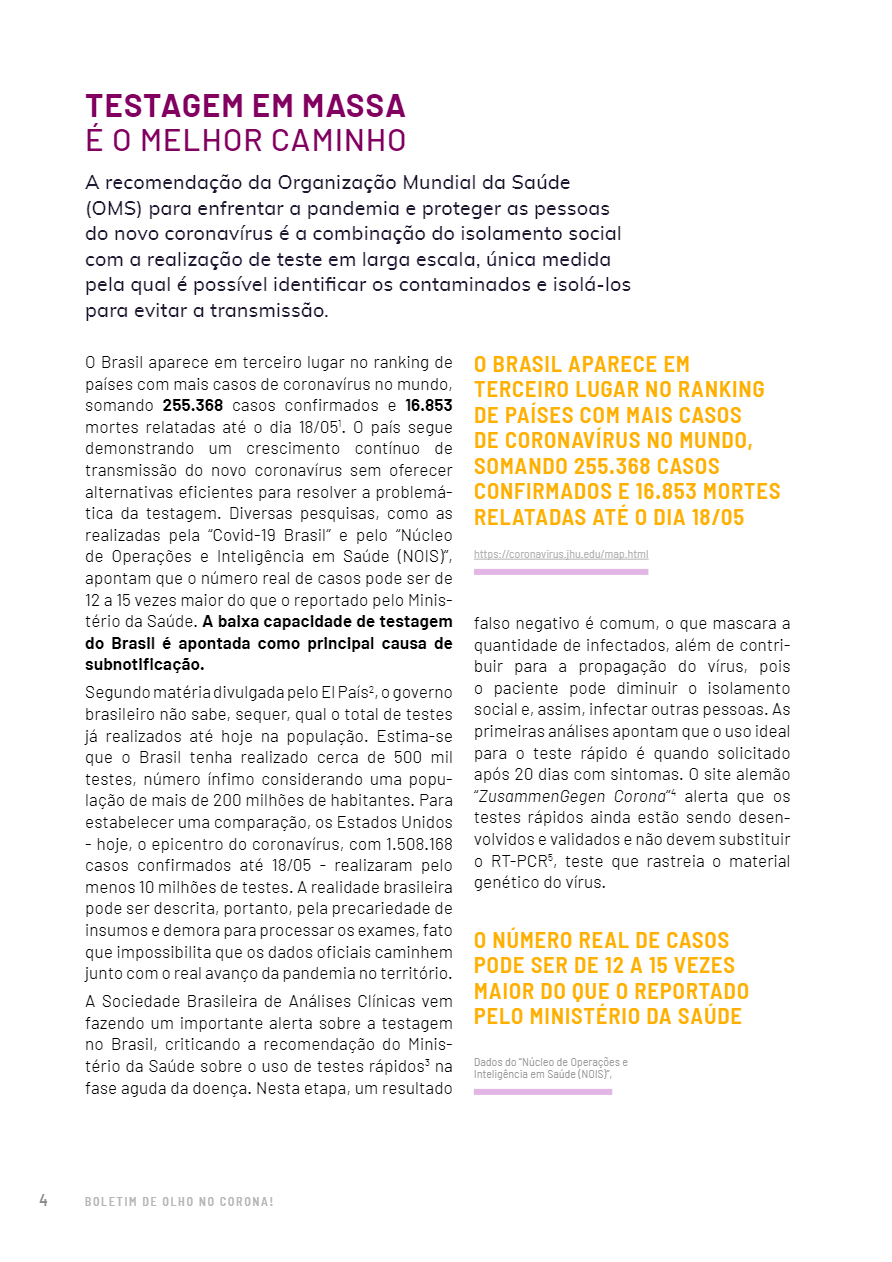

De Olha no Corona, No. 3, 21 May 2020.

For Data Labe, it is vital to ensure their work is accessible to the community, both by being free and relevant to their audience:

‘We write articles with slang and informal expressions. We have no intention of acting or looking like a formal vehicle of communication. Colloquial terms such as “quebrada” (home or neighbourhood) and “vida loca” (crazy life), are common in our articles, because it draws in our readers. This is how our readers speak in their everyday conversations with friends and neighbours. They are people who don’t speak like teachers or the mainstream media.

‘Since we work a lot with data transparency, especially when it comes to this particular project, we thought, “We’re monitoring Covid, but we also want people to independently input their data and say whether they’ve tested positive or not. That’s what the authorities should be working on, right?

‘Our databases are all public. Nowadays paywalls have become common for newspapers like Folha de São Paulo, but either you want to facilitate communication or you don’t, right? There are times when you want to perform data analysis from some source, or download this or that, but you can’t because you have to pay for it. All our analyses are done by using free software. We do not pay a penny to use any of the licenses. It’s not that we are pirates. We start the programme from scratch, and then we make it all available through a hub… [For example], the dashboard’s database has a postal code entry section, so all confirmed cases that have been inputted into the database can be traced back to a location.

‘[W]e built from the bottom-up because we know how crucial this stuff is. If it wasn’t done this way, we would never be able to map out real scenarios and realities. Our work was therefore to support local networks that had already said they were up for creating platforms to track Covid-19 cases. We helped them with the operational side of things, always with data transparency in mind, thinking of why it’s important and how best to deliver it.‘

President Bolsonaro maintained his popularity in the polls thanks to emergency cash handouts to the poor and his attitude that quarantines don’t pay bills. By summer 2021, all this began to change. Protests against the president’s policies that had by then led to over half a million deaths, and corruption scandals relating to the purchase of vaccines, made his populist rhetoric redundant. The scaling back of the emergency social program added increased economic insecurity to the national trauma caused by a surge in cases. One survey by newspaper Folha de S.Paulo suggested that over half the Brazilian population was in favour of impeaching Bolsonaro for his handling of the pandemic and the ensuing scandals. By December 2021, his approval ratings had dropped to a record low of 22 per cent.

However, organization to spread awareness and empowerment has been largely successful. One highlight came from São Paulo’s governor, João Doria. The governor played a key role in MC Fioti’s viral funk track/video, which changed the hyper-sexualized lyrics of the original song into to an anthem that celebrates Instituto Butantan, the São Paulo vaccine manufacturer that was producing Coronavac, and encourages people to get vaccinated:

A vacina é saliente, [The vaccine is coming]

Vai curar nois do virus, [It’s going to cure us of the virus]

E salvar muita gente. [And save a lot of people]

In Maré, the De olho no Corona campaign continues to publish a newsletter with information about the developments of the pandemic in Brazil as well as providing free services for the residents of the Maré favela including Covid-19 testing, online consultations with doctors and psychologists and support for safe isolation.

A year out of school

As across much of the world, schools and educational institutions in Latin America closed with the arrival of the pandemic. In March 2020, every country in the region apart from Nicaragua closed their schools. By August 2021, the education system across Latin America and the Caribbean had been fully or partially closed on average for 347 days.

Educational content was often broadcast on television and radio, to which the majority of the region’s population has access (90 per cent of households have a television and just less than three-quarters have a radio). However, many families, especially in poorer areas, lacked access to the internet or to devices to access the internet. According to a report by the OECD, in 2018 less than 14 per cent of poor primary school students (those living with less than $5.50 per capita per day) had a computer at home with an internet connection. Meanwhile students attending public schools were less likely to receive online teaching than those in private schools. Both of these facts raise serious concerns for social mobility and point to wide socioeconomic gaps in education.

The ongoing economic crisis in Venezuela had degraded the country’s telecommunications system before the pandemic, often causing blackouts. During the pandemic, demand exceeded supply and in May 2020, Venezuela had the slowest fixed broadband download speed globally, and the third slowest mobile download speed.[4]

In Uruguay, on the other hand, the Plan Ceibal program that provides a free laptop and internet connection to every child was stepped up to reach 85 per cent of primary students and 95 per cent of secondary students and teachers. Nonetheless, only 30 per cent of teachers took advantage of the connection to hold live video-conferencing classes with their students.

Chile

Mapuche children in Chile already faced difficulties in accessing education before the pandemic. Onésima explains why she and her colleagues founded the Network for Mapuche Childhood (Red x la Infancia Mapuche):

‘[Mapuche] children living in poverty have a right to education. That right has been denied by violence, negligence, and racism. We consider having no schools in Indigenous communities to be an act of racism. A lot of children [in Wallmapu] aren’t learning to read or write. They don’t have any type of recreational activities outside of their communities or away from violence, because the territory here in the south is militarized. That militarization means there are a lot of police with weapons in the communities, mainly attacking children. Children! By focusing on attacking children, they’re also able to hurt the parents and wider community.

‘The schools in the Indigenous communities or nearby have been victims to attacks and arson. Schools have been set on fire. So the only educational spaces the children have left are outside of their communities. This means they take risks on the journey, because there have been a lot of attacks on children on their way to school: they’ve been shot at or made to get out and walk… Others have been victims at school, such as the arson cases or tear gas attacks on the smallest children in their first year. They allow attacks in schools, which I think is deliberate. Access to education and the right for children to share with their peers in a safe learning environment is denied to them due to violence and fear. Burning a school down spreads fear in the community because they’re attacking the children’s only safe space. Many schools have no reliable drinking water supply, which produces other negative impacts like health problems.

‘There’s a significant school dropout rate because children do not have access to schools in their communities and have to travel to larger cities to be able to receive an education. This means that children and teenagers have to go to boarding schools; they live away from home to learn.‘

During the pandemic, those boarding schools closed. However, many Mapuche children do not have access to resources to continue learning remotely, as Onésima explains:

‘Before the pandemic…. a lot of children had to leave. They would only come back on weekends, but during the week they were outside of their communities. Now, with the pandemic, these boarding schools aren’t running. The children that don’t have anywhere to learn quite simply go without an education. This lack of schooling nowadays isn’t made any easier with online classes, because there’s no Wi-Fi in rural communities. There’s no internet connection and the families don’t have devices like a phone or computer. So, we’ve found ourselves neglected like this for about a year now. Children remain without teachers to come into their communities and teach; they don’t facilitate access to education. We also find ourselves with a government that has totally ignored the importance of rural education in Chile.‘

The Red has been working in their community to help Mapuche children and ensure they do not miss out on their education due to the pandemic. However, with limited resources and risking their health not only due to Covid, Onésima laments that they couldn’t help more.

‘[We haven’t been able to help] all the children, but in specific cases we’ve been collaborating to produce educational material. We’ve worked in a more personalized way with the children, delivering material and guiding parents on how to help their children learn. With other children, we’re starting to register them to take remote exams. That way the children don’t have to keep retaking exams and can move on to the next level by learning from home. Those of us travelling about are the ones giving the classes. We go to their houses because there isn’t a specific place where we can do it otherwise. This is something the network has carried out very independently because nowadays it’s really difficult to access the communities with so much militarization and police persecution.‘

Colombia

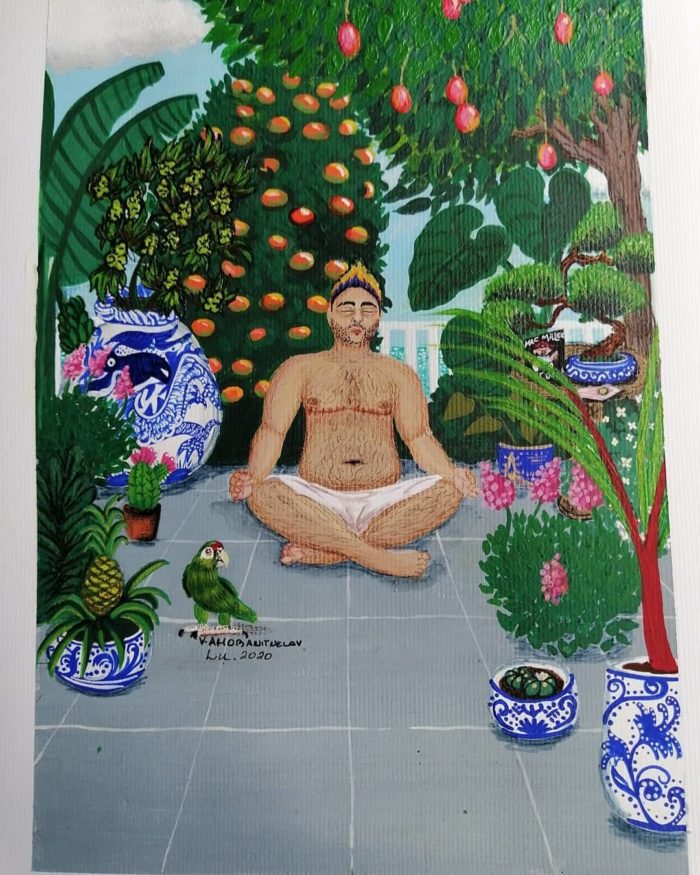

Beyond missing out on education, not being able to go to school has had serious and immediate consequences for some children in Latin America. In some rural areas of Colombia, children’s absence from school has led to them being recruited into armed groups.

Hilda Molano Casas is the coordinator of the technical secretariat of the Coalition against the Involvement of Children and Young People in the Armed Conflict in Colombia (COALICO). COALICO is a group of civil society organizations working to defend the rights of children and adolescents. Specifically, they aim to make visible and reduce the impact of the armed conflict on children, especially the involvement, recruitment, or use of children in the conflict. For the past 12 years, COALICO has also contributed to the UN’s monitoring of children and the armed conflict. Hilda explains the importance of schools in preventing recruitment:

‘For a space such as ours, monitoring education makes perfect sense as part of our commitment to monitoring the issues that affect children, and the work we do to prevent recruitment and other forms of violence… It allows us to work with the educational communities beyond the children, including the teachers, the management structures of the educational institutions, and the parents and caregivers of the children, and from there to the community… School has become par excellence the place where children must be protected …, but at the same time there must be conditions to guarantee the protection of the school.’

The landmark signing of the peace agreement between the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) and the Colombian government in 2016 reduced the extent of the conflict. The recruitment of and violations against children also fell. Since the signing however, some demobilized members of the FARC have returned to arms while others never demobilized. Hilda explains:

‘This has meant that between the years 2017-2019 we have seen a rise in the number of attacks on schools, threats to teachers, displacement, [… and an] increase in accidents with anti-personnel mines and unexploded ammunition. When the pandemic arrived in 2020, between March and June we saw almost equal numbers of children recruited [into armed groups] as in 2019 as whole. Our calculations tell us that…there was a 500 per cent increase in this period from one year to the next.

‘One reason for this remarkable increase in the recruitment situation was the closure of schools.[…]During the period of strictest quarantine, which for us was between March and July last year, this type of violation [recruitment] really shot up. There we found a relationship that in practice shows us the link between the school and recruitment.

‘When schools closed, the need for access to virtual media brought to light other issues. One of these is that it has become easier for children to access the internet and also for armed groups to be able to contact them. Social networks and virtual media became part of a dynamic recruitment process. And on the other hand, unfortunately we have encountered situations where the armed group has hacked into the school’s accounts and got into the [virtual] class with the children. So on a normal school day, the armed group, although they no longer occupied the school, could penetrate the virtual classroom.‘

Despite the new challenges, Hilda and her team have worked to ensure that children are able to stay in school. Unfortunately, however, too many children continued to join the armed groups, as Hilda explains:

‘It was not only for reasons of the conflict that the closure of schools was a problem, but that in many cases, especially in rural areas but also in cities, accessing virtual media has been impossible. There are no conditions for children to be able to stay in the education system, either because of access – the technological resources are not available for this to be possible – or because of the increase in certain expenses that families have not been able to cover in the majority of cases, which is to have an internet connection in their home or even a mobile or computer. We have had cases of families with at least 3 or 4 children, who are at different school levels, all have to access the same mobile phone, on top of the work that the father or mother can do.

‘So from 2020 to 2021, there was a high percentage of dropouts. In the areas where we have worked, [this was] up to around 20 to 30 per cent… Effectively, this virtual learning, having to make certain efforts, not having the conditions, [and] finding other alternatives for survival have discouraged young people from staying in school. Finally, for them sometimes staying in school serves only to pass the time, because what does it guarantee? Reaching a different level or earning another type of income sometimes is not a realistic prospect for their daily life. It’s very, very difficult to convince them to keeping making those extra efforts.

‘With the pandemic, it became clear that many of them ended up going to the armed groups, because there was no way to guarantee the conditions to stay in the system. Many of the students who left told their teachers, “I wanted to study, but it wasn’t possible.“‘

Recovery from the pandemic in rural Colombia, at least for children and their teachers, will not be easy. However, there is a determination from everyone involved to make children’s rights heard and to prioritize education. Hilda explains:

‘If it was difficult before, now it is much more difficult to think about reopening schools, to think about teachers being able to come in. In other words, now it is much more complex to think about returning to something that looks like normality. What they had before [the pandemic] was not good, but it is not even possible to return to that, especially in the area of greatest exclusion, violation, and the most dispersed areas of the country, which is where the impact of the conflict has been most felt.

There are voices in the territories saying, “I don’t want to be a war machine.”[5] And that seemed to me to be the most difficult thing. It brings a tear to your eye when a child says, “I want to be something else. Even though I don’t go to school – I can’t go to school – I can have a chance and I want to do something else [besides being a guerrilla].”

‘I definitely think that for a country like ours, for Colombia, times are not going to be easy, because unfortunately we have been living in a situation that we haven’t seen for ten or fifteen years. But one thing that persistence has taught us is that if we were not doing what we are doing – as small as it may be -, if there were not a voice to stand up and say that this should not have happened, the situation would be worse. It should not be like this. Certain institutions have to be changed, because everything has been lost […]. With our social movement peers, we have to grant [children] a space [in the human rights movement]. We have to continue working for them and keep demanding.‘

Despite a slow start, mostly due to a lack of supply, vaccination rates are generally high in the region. From being one of the worst affected regions it has become one of the best prepared to take on the virus. Cuba has vaccinated over 90 per cent of its population, including children aged just two, with vaccines developed in the country. In Brazil, despite President Bolsonaro’s falsehoods, vaccine take up has reached one of the highest levels in the world. Meanwhile Chile became the first country in the world to offer a fourth shot to immunocompromised citizens.

Nonetheless, as Brazil and Costa Rica head toward presidential elections in 2022, following Colombia’s elections earlier this year, other questions about recovery from the pandemic will be key points of debate – as they were in Chile’s elections at the end of 2021.[6] Recent trends in the region suggest a new ‘pink tide’ and an appetite to shift away from the political establishment. This is perhaps due in part to the pandemic’s lessons and sufferings, and may offer some hope for those working for social change and justice.

For the present, the pandemic continues in Latin America but the additional challenges it has posed for the region’s vulnerable communities will remain long after it has subsided. As social justice leaders continue to make their causes seen and heard, and to demand the resources and support they need, it gives hope that the post-pandemic period may see a fairer world for their people.

Interviews

Hilda Molano Casas (COALICO – the Coalition against the Involvement of Children and Young People in the Armed Conflict in Colombia): interviewed via Zoom on 20 April 2021 by Emily Gregg. Translated by Mark Wilson.

Isabel Muñiz (CAMI Zihaukali): interviewed via Zoom on 30 June 2021 by Emily Gregg and Antonella Navarro.

Juarez Munduruku (Sawré Muyby Village, Brazil): interviewed via Jitsi on 31 January 2021 by Nayana Fernandez. Translated by Sara Da Costa.

Lu Gilberto (Hombres Trans Feministas). Interviewed via Zoom on 5 June 2021 by Emily Gregg and Antonella Navarro. Translated by Antonella Navarro.

Marcos Angel Brito Uriana (Wayúu community, La Guajira, Colombia): interviewed via Zoom on 1 February 2021 by Tom Gatehouse. Translated by Will Huddleston.

Onésima Lienqueo (Red x la Defensa de la Infancia Mapuche): interviewed via Zoom on 14 April 2021 by Emily Gregg. Translated by Natasha Tinsley.

Paulo ‘Polinho’ Mota Medeiros Jr.(Data Labe): interviewed via WhatsApp on 25 February 2021 by Gianna Giordani. Translated by Elenice Araujo and Gianna Giordani.

Sofía Lozano Snively (Alternativas Pacíficas): interviewed via Zoom on 16 June 2021 by Emily Gregg and Antonella Navarro. Translated by Fernanda Alvarez Pineiro.

References

Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL) et al. (2021). The Impact of COVID-19 on Indigenous Peoples in Latin America (Abya Yala): Between Invisibility and Collective Resistance. CEPAL. Available at: https://www.cepal.org/sites/default/files/publication/files/46698/S2000893_en.pdf.

CEPAL (2021). The Pandemic in the Shadows: Femicides or Feminicides in 2020 in Latin America and the Caribbean. CEPAL. Available at: https://oig.cepal.org/es/documentos/la-pandemia-la-sombra-femicidios-o-feminicidios-ocurridos-2020-america-latina-caribe.

Comisión Interamericana de Mujeres (2020). Covid-19 en la vida de las mujeres: Razones para reconocer los impactos diferenciados. Cuaderno Jurídico y Político, Volume 6(15), pp. 97-107. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5377/cuadernojurypol.v6i15.11159.

Gielow, I. (2021). Datafolha: Maioria acha Bolsonaro desonesto, falso, incompetente, desprepardo, indeciso, autoritário e pouco inteligente. Folha de S. Paulo. Available at: www1.folha.uol.com.br/poder/2021/07/datafolha-maioria-acha-bolsonaro-desonesto-falso-incompetente-despreparado-indeciso-autoritario-e-pouco-inteligente.shtml.

Intersecta et al. (2020). The Two Pandemics: Violence Against Women in Mexico amidst COVID-19. Available at: https://equis.org.mx/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/report_thetwopandemicsF.pdf.

Islam, M. et al. (2020). COVID-19–Related Infodemic and Its Impact on Public Health: A Global Social Media Analysis. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine, Volume 103(4). Available at: https://www.ajtmh.org/view/journals/tpmd/103/4/article-p1621.xml.

Martin et al. (2020). ‘Violentadas en Cuarentena’. Distintas Latitudes. Available at: https://violentadasencuarentena.distintaslatitudes.net/actions-prevent-gender-violence/.

PROVEA (2020). Civil Rights Violations Patterns 2 Months into the State of Alarm in Venezuela. PROVEA. Available at: https://provea.org/publications/researches-and-investigations/report-civil-rights-violations-patterns-2-months-into-the-state-of-alarm-in-venezuela-1/.

Santiago Ortiz Correa, Javier, Marco Valenza, Vincenzo Placco, and Thomas Dreesen (2021). Reopening with Resilience: Lessons from Remote Learning during COVID-19 in Latin America and the Caribbean. UNICEF. Available at : https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/Reopening-With-Resilience-Lessons-from-remote-learning-during-COVID-19-Latin-America-and-the-Caribbean.pdf.

Speedtest Global Index. ‘Venezuela’s Mobile and Broadband Internet Speeds’. Accessed 14 July 2021. https://www.speedtest.net/global-index/venezuela.

Tapia Jáuregui, Tania (2020). ¿El Pico y Género fue tan exitoso como asegura la Alcaldía? Los datos muestran otra cosa’. Cerosetenta. Available at: https://cerosetenta.uniandes.edu.co/el-pico-y-genero-fue-tan-exitoso-como-asegura-la-alcaldia-los-datos-muestran-otra-cosa/.

World Health Organisation (WHO) (2021). Fighting misinformation in the time of COVID-19, one click at a time. WHO. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/fighting-misinformation-in-the-time-of-covid-19-one-click-at-a-time.

World Bank (2021). The Gradual Rise and Rapid Decline of the Middle Class in Latin America and the Caribbean. World Bank. Available at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/35834.

World Health Organisation (2021). Violence Against Women Prevalence Estimates, 2018: Global, Regional and National Prevalence Estimates for Intimate Partner Violence against Women and Global Regional Prevalence Estimates for Non-Partner Sexual Violence against Women. World Health Organisation. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240022256.

Woskie, Liana R., and Clare Wenham (2020). Do Men and Women “Lockdown” Differently? An Examination of Panama’s COVID-19 Sex-Segregated Social Distancing Policy. MedRxiv. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.30.20143388.

About the author

Emily Gregg is a LAB correspondent and author, and manager of the ‘Covid-19: Loss, Survival, Recovery, Transformation’ project. Emily lived in Arica, Chile until returning to the UK due to the pandemic from where she produced a series of regional Covid updates. She is currently based in Concepción, Chile. Emily was also author of the Student Revolution chapter of the Voices of Latin America project.

[1] Official government data shows that vaccination rates in La Araucanía were similar to those across Chile. However, those data do not disaggregate Indigenous vaccination rates compared to non-Indigenous population in that region. We contacted Mapeando el Coronavirus en Wallmapu for information but did not receive a response.

[2] Some Indigenous communities and organizations recorded Covid-19 related data themselves, for example the National Committee for Indigenous Life and Memory in Brazil, and the National Coordination for the Defence of Indigenous and Campesino Territories and Protected Areas (CONTIOCAP) in Bolivia, and the Coordinating Body for the Indigenous Peoples’ Organizations of the Amazon (COICA). In Mexico, cases are disaggregated by Indigenous language speakers, with a monthly overview of data for people identifying as Indigenous.

[3] Methods to access the helpline also increased during this time.

[4] Fixed broadband speed has steadily increased in Venezuela since May 2020. As of May 2021, it sits at 140/180 countries with a download speed of 18.53 Mbps.

[5] Colombia’s Defence Minister, Diego Molano, described child soldiers as ‘máquinas de guerra’ (war machines) in a speech justifying the March 2021 bombing of guerrilla forces, which killed at least one minor.

[6] Elections also took place in Nicaragua in January 2022, which incumbent President Daniel Ortega won, although amongst much criticism and doubt over the freedom of the elections.

Main photo: Mural outside the public hospital in Concepción, Chile. Credit: Emily Gregg.

All other photos, unless otherwise stated, have been kindly provided by the interviewees.