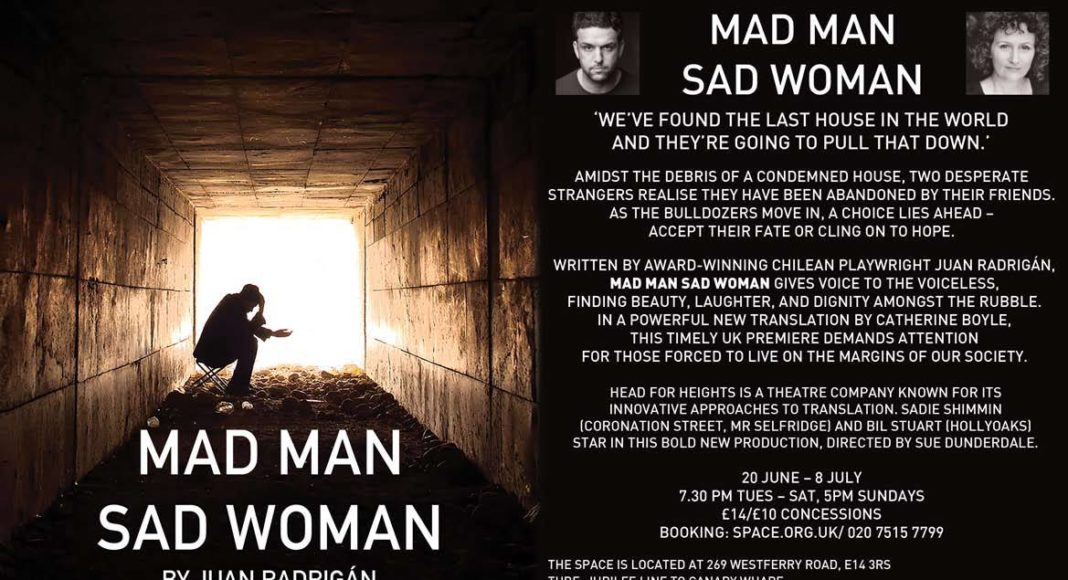

‘Mad Man Sad Woman’, by Juan Radigan, is on at The Place, 269 Westferry Road, London E14 3RS, until 8 July. Tickets from www.space.org.uk

Translated by Catherline Boyle. Directed by Sue Dunderdale.

with Sadie Shimmin and Bil Stuart.

To write a work of art about absolute deprivation is a never-ending challenge. The most absolute deprivation is death itself, but there are uncounted ways of living on the verge of death, when individuals undergo extreme physical and mental suffering. Destitution is a statisticians’ term to describe people at the extreme of poverty, but how to describe life with absolutely no resources whatsoever? To bring such a life ‘to life’ it has to be infused with something other than material emptiness: it is a kind of raising of the dead, though the raising we see in this play hardly brings much merriment. This is what Juan Radigan, the Chilean playwright who died last year, has achieved. What less promising raw material could there be than two people thrown together by chance, sharing a shelter which barely merits the name, the one terminally sick because of his alcohol consumption, the other born with a lame leg since birth and with not a penny between them. Their cardboard shelter is under sentence of demolition yet there is no escape. In the interminable, testy exchanges, the hardened small-time criminal and the prostitute, both retired (in a manner of speaking), bicker and taunt one another about nothing in particular, yet manage to keep the audience riveted on their physical and existential cul-de-sac. The exchanges are full of dark humour: ‘you are more touched than the bell of a whorehouse’ (‘estás más tocada que el timbre de una casa de putas’) is one which sticks in my mind. At one point Huinca looks into Eva’s eyes and says they remind him of someone; she gets excited and then he says – ‘yes they remind me of a man I once killed’; she’s had an easy life, he tells her – ‘you made a living lying down’. Prisoners in their own plotless endgame, Eva and Huinca (a nickname which is the mapuche word for a ‘white’ or ‘Spanish’ Chilean, though if the truth were known they all have a drop or more of indigenous genes) speak of another place where they might be. At one point she seems to go off to the plaza in a fruitless search for punters, and later she tries to conjure up an idyllic image of ‘over there’ – of their imminent life after death, which Huinca ridicules. They try to make a meal of a few bits and pieces she has salvaged- a tomato and a biscuit which remain untouched. Eva even tries heroically to conjure up a romantic atmosphere – ‘let’s get married!’, she says at one point, and she tries to dance, to sing, to construct a wedding ceremony, but it all falls flat. The barbs go on and the steamroller growls. Eva never sits down, throughout the 90 minutes of the performance. She is constantly on the move, gathering up her things in plastic bags in one corner of the tiny square stage and putting them down in another, making as if to escape. Yet still she manages to sustain the exchanges. Played by the unceasingly energetic Sadie Shimmin, she faces the premature end of a life in which from the first day she has suffered at the hands of others – her mother, who neglected her and threw her out of the house at the first opportunity, giving her no choice but to sell her body; and the men. Bil Stuart gives multi-faceted expression to Huinca’s suffering in his extreme pain and his aggression, not least towards himself: he picks up a bottle for the last time and drinks even while Eva implores him not to, because they both know that it will kill him. The play is stuffed full of chilenismos posing difficult challenges to the translator, surmounted brilliantly by Catherine Boyle. The Director, Sue Dunderdale, has made sure the play keeps up momentum, as it must to sustain the repartee which is fuels it. The show is a production of Head for Heights, a theatre company devoted to translating and producing work about people living on the margins and doing so for the benefit of audiences who also ‘have direct experience of marginalisation’. The play is on at The Space, a small converted round church which favours an intimate circular audience arrangement particularly well-suited to this play.