This article is based on an interview carried out by ABColombia in August 2018.

The text does not reflect the views of ABColombia rather the personal views of two women of the FARC who took part in the reintegration process during the Santos Government and their experiences between 2017 and 2018.

For more information on women and the Colombian Peace Process, please see the ABColombia Report “Towards Transformative Change”.

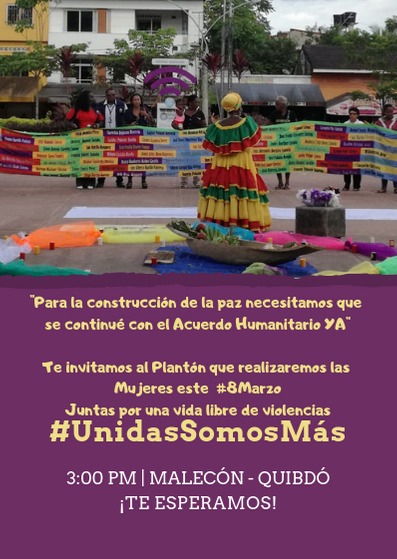

QUIBDÓ. This is the story of two sisters whose lives have been shaped by the FARC. Edy (35), an ex-combatant participating in a reincorporation programme; and Yorladis, her younger sister, who works for the newly formed political party of the FARC. Because of the armed conflict, the two sisters grew up apart; the Peace Accord brought them back together. In summer 2018, they met with ABColombia to talk about the past, but also about their hopes for a better future: for peace, social justice and equality for women.

‘I want people to see us as persons, not only as ex-combatants,’ says Edy Baitá. ‘I want them to see us as women who can work against gender discrimination and the macho culture’.

When we met in Quibdó, Chocó, Edy arrived incognito, worried about her security. She asked if her sister had arrived; when she learnt that Yorladis was not there, she started calling her to see where she was. It turned out she was OK and not far from Quibdó.

Edy talked about the difficulties of re-incorporating into civilian life. To be known as an ex-FARC combatant is very dangerous, she tells us. That is why the FARC preferred to live together for their security, in the Transitory Zones for Normalisation (ZVTN). However, the Santos Government had significantly failed to provide adequate conditions for them to live in these zones – there was a lack of sanitation, clean water, food, electricity and extremely poor housing and, as a result, she had decided to leave the zone.

Edy

Edy was a member of the FARC for 20 years; she joined the guerrilla when she was 15 years old, after her family had been forcibly displaced.

When Edy speaks about the reincorporation process, you can feel her anguish. When she laid down her weapons, she had high hopes, especially in relation to her education and career. Edy had been a nurse in the FARC, but her qualification was not recognised by the Colombian Government, so her dream was to obtain her bachillerato (high-school diploma) and then officially train as a nurse.

We were prepared for reincorporation, but we expected food, housing, employment and education. The state has not fulfilled this agreement.

– Edy Baitá

Education is a crucial point: ‘I was told that the only training I could get was to become a bodyguard or security guard. I did not want that, because it seemed like continuing with what I had done previously. I’ve always wanted to be a nurse and work in the communities, because I have seen the poverty and desolation there. I know people from the cities don’t really like going there. For me it’s no problem, I am used to being in the mountains, and I would like to help the communities.’

In Quibdó, Edy is part of a group of female ex-combatants. They have their own projects and ask for support. The sense of community is still very strong among them. ‘Everything I do, I do for the collective.’, Edy says. However, there are obstacles that have made it difficult for them to start their new life. One of the problems Edy highlights is that ex-combatants have no land to work.

Machoism still rules in Colombia. I feel that nobody really listens to the women of Chocó. I want women to have a voice. In the FARC, we did have a voice.

– Edy Baitá

Edy explains that women in the FARC were free to have relationships, but they used birth control. Pregnancies were a security risk, and life in the guerrilla was not safe for children. She went on to tell us that she had borne two children whilst in the FARC. The first, a girl, she had left with her family, but the little girl had an accident when she was only two years old and drowned. Then Edy had a little boy; when he was two months old, he was given to the father’s parents to look after. ‘I wanted to be a mother,’ says Edy, ‘but I knew: either I give him away, or they take him away from me.”

In the FARC, Edy says, she received an education. She was taught to read and write and later she trained as a nurse.

‘In the guerrilla, we were free,’ she says. ‘As women, we used to do the same things men did. There was no discrimination, men and women respected one another. We were never housewives. Men had to do the laundry, they had to do everything. Women were seen as capable persons. Maybe life was better for women in the guerrilla than in society.’

The guarantees of political participation provided in the Peace Accord and the international support for this created high expectations among former FARC combatants. However, they are worried about the implementation of the first Chapter of the Accord on the Integrated Rural Reform. This was a central point for the FARC, but not much of it has been put into practice. Another big concern is the security of ex-combatants. Edy does not feel safe. She fears she may endanger her family, so she cannot tell people about her past and avoids going out at night. Edy visits her family now but is introduced as a relative who was working in another city and has now moved back to Chocó. It is not safe to be known as an ex-FARC combatant.

Yorladis

Yorladis was still quite young when her older sister left. At first, Edy visited her family from time to time, but then she realised she was putting them in danger and so, although she missed them, she decided not to visit them anymore.

Not knowing whether Edy was dead or alive was difficult for the whole family, but particularly for her mother. During the demobilisation process, before Edy got back in touch with her family, her mother was told that Edy had been killed in combat. Someone had spread that lie on purpose. It was a shock for her mother, but for security, the family had to pretend that they did not know Edy. They were not allowed to show their feelings and enquiring about their daughter was risky.

Yorladis had always sympathised with the FARC; she became part of the underground political party of the FARC, the Clandestine Colombian Communist Party (Partido Comunista Clandestino Colombiano – PC3). Many times, she had played with the idea of following in her sister’s footsteps to take up arms. Today, she is actively involved in the political party of the FARC, where she works on projects promoting gender equality. At the moment, she is part of a project supporting single mothers in poor neighbourhoods in Quibdó.

We have not given up our political ideal to transform society, and we won’t give up until our dream of a decent country with social justice and equal opportunities for all Colombians has come true.– Yorladis Jimenez

The family must be cautious not to reveal Edy’s real identity. However, Yorladis is also worried about her own security. She spends a lot of time in the office of the political party, was seen in many of the political campaigns during the elections in 2018. When she goes to events, she has to ask for police protection. ‘The police have been very good with me’, she says.

I think that today more than ever, our security depends on being as visible as possible. We have nothing to hide from Colombian society or the international community, and it is the State that is responsible for guaranteeing our security. We believe in the institutions, even if they are fragile, but we believe in the fragile institutions.

– Yorladis Jimenez

At the moment, Yorladis is still waiting for her accreditation by the Colombian State through the Office of the High Commissioner for Peace, as a member of one of the structures of the now defunct FARC-EP. She emphasises that there were different structures within the FARC-EP: the guerrilla fronts, the militias, the Bolivarian Movement and the PC3, the structure in which she developed her political activities. Yorladis is worried, because the procedural delays in obtaining her accreditation have affected her reintegration into civilian life economically, socially and politically.

What next for peace?

Both sisters emphasise how grateful they are for the support of the international community. ‘If the international observers were not here, the peace process would already have collapsed.’, says Yorladis.

However, both sisters express concerns about the lack of certainty regarding the future of the agreements made in the Peace Accord. Edy and Yorladis want peace, but it is very unclear what aspects of the Peace Accord the new president, Ivan Duque, will implement.

‘Do you think peace will last?’, asks Edy. ‘Will they implement the Peace Accord?’

ABColombia recently published a report about the implementation of the gender focus in the Colombian Peace Accord. The report contains a chapter on the reintegration of women of the FARC. You can access the report in English and Spanish.