This report was prepared for LAB by Linda Etchart, author of the chapter on Indigenous People’s in LAB’s Voices of Latin America. Linda is a lecturer in Human Geography at Kingston University, and author of the chapter ‘Indigenous Peoples and the Rights of Nature’ in LAB’s 2019 book Voices of Latin America.

N.B. Figures for Covid-19 cases and fatalities in some of the images may differ from those in the text, where the figures given are the official Ecuadorian government statistics for 31 March 2020

31 March 2020

Ecuador is the country with the fifth highest number of corona virus cases in Latin America, yet is one of the smallest, between Guatemala and Bolivia in size of population. It has the ninth largest population of the continent with just short of 18 million inhabitants.

There were around 2,302 cases of COVID-19 in Ecuador confirmed on 31 March 2020, according to state figures. At least 79 people had died, indicating a death rate of 3.35%. (El Universo 31 March 2020). A nationwide shutdown was in place until at least 5 April.

There were 3,252 suspected cases, 2,485 negatives, and 54 people acute cases hospitalised, with 7,982 tests conducted.

On 31 March, those in self-isolation numbered 1,805, in a stable condition in hospital 206, and with uncertain prognosis 100. There were 1,209 men and 1,031 women confirmed infected. The age of those most infected was between 20 and 49 years old, with, 1,320 cases.

The vast majority of cases of COVID-19 were in the coastal province of Guayas, where the largest city in the country, Guayaquil, is located, with around 900 cases in Guayaquil itself, and where the mayor, Cynthia Viteri, had tested positive. It was reported that there were bodies in the streets of Guayaquil (El Universo 31 March 2020), and that 100 bodies had been collected from homes in the last 3 days.

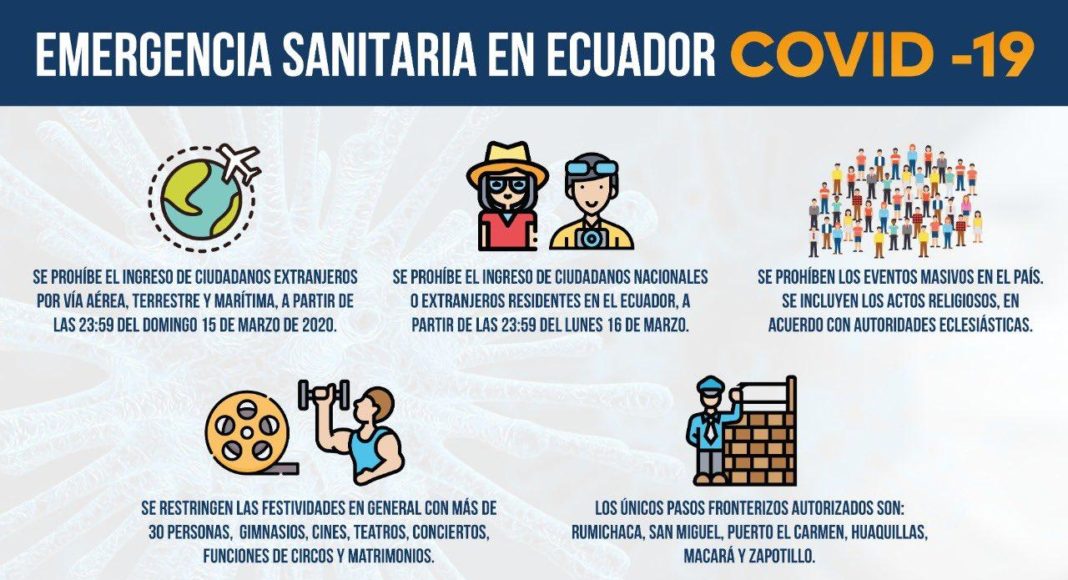

Government action in the crisis

A number of measures had been implemented: a ban on entry from abroad, a curfew from 2pm to 5 am, a ban on public and private events; the closing down of Yasuní national park to tourists. Food banks had been mobilised with the support of Diakonia, the Archdiocese of Cuenca, the National Police and the municipality of San José, among others.

On top of the existing US$60 Family Protection benefits, from 1 April, 400,000 of those most in need will receive extra state benefits, as will the 1 million citizens who receive occasional Human Development benefits. This will be in place for April and May (El Universo 31 March 2020).

The Ecuadorian government was crowdfunding for donations of US$5, $10 and $20, to buy survival kits of basic food for the most needy, with the goal of providing 1 million kits, supported by donations from philanthropists, and efforts by scientists to design and manufacture ventilators. The Chambers of Commerce of Quito, Guayaquil and Cuenca were stepping up with support.

In Guayaquil, Mayor Viteri announced that the US$10 million funds reserved for the city’s bicentennial celebrations would be diverted to requirements to combat the coronavirus; and on Sunday 29 March, she announced the purchase of 50,000 protective masks, 40 ventilators and 6,120 sets of protective clothing. Thirty new beds were being made available for homeless people who would be kept in a facility separate from the existing homeless people’s hostels, whose inhabitants feared contagion. Telemedicine advice from doctors was available on computers and mobile phones for those who had access to the internet (El Universo 30-31 March 2020).

Fears for indigenous peoples

With regard to the indigenous peoples of Ecuador, there were fears that they were in the gravest of danger from COVID-19. Data on the relative vulnerability to the new virus of Latin American indigenous communities was not available, although data gathered from indigenous communities in Australia, Canada and the USA affected by previous viral epidemics indicated that the indigenous people in those countries were three to seven times more likely to suffer severe consequences.

Indigenous people’s health is often precarious, as they have less immunity to infections common to the rest of the population; in indigenous communities the prevalence of diseases such as hepatitis B, tuberculosis, malaria or dengue is high, and their access to health care is limited (Sierra Praeli 2020). The majority of the indigenous population of the Ecuadorian Amazon were killed by disease soon after the arrival of the colonisers in the sixteenth century (Newson 1995): for those communities that have survived, the COVID-19 threatens both those who endeavour to retain their cultures and a more-or less self-sufficient way of life, and those who continue to live in voluntary isolation but who have occasional contact with the outside world.

By the week beginning 16 March 2020, COVID-19 had already spread to the northern Ecuadorian Amazonian province of Sucumbíos, home to several indigenous groups, where a tourist visiting the Cuyabeno nature reserve tested positive. Another case was reported in the southern province of Morona Santiago, also inhabited by a number of indigenous communities, with the reported cases increasing to six in both provinces (Brown, Al Jazeera, 26 March 2020).

Mobilising against infection

Over the entire Amazonian region, indigenous people have been mobilising against the virus, with the support of Coordinator of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon River Basin (COICA), the umbrella organization of the indigenous communities of the Amazon rainforest inhabiting Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guyana, Peru, Suriname and Venezuela. COICA requested that all the governments of the nine member countries take measures to protect the indigenous peoples from the virus, such as controlling entry into indigenous territories (Sierra Praeli 2020). All of over the Amazon, indigenous communities are responding to the recommendations of COICA and have taken their own initiatives, as COICA has called on them to do.

In Ecuador, the president of the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of the Ecuadorian Amazon (CONFENIAE), Marlon Vargas, declared that if the virus spread among the country’s 500,000 indigenous Amazonians, it would constitute an extermination. CONFENIAE issued an order that access to the Amazon rainforest should be closed, and that all the companies engaged in oil drilling, mining, logging and hydroelectric projects should prevent movement of personnel and suspend their activities near indigenous communities (Collyns et al., The Guardian 30 March 2020]

The Shuar, one of the most numerous and powerful of the Ecuadorian indigenous nationalities, took the lead in closing off their villages to outsiders. The Guardian reported that in late February, weeks before Ecuadorian president, Lenín Moreno, ordered a nationwide lockdown, Shuar indigenous leader Tzamarenda Estalin placed a sign at the entrance to his village that read: ‘Entry forbidden as a health precaution.’

Similarly, the Achuar Nationality of Ecuador (NAE) prohibited the entry of tourists to its territory and requested that the lodges that host foreign visitors remain closed (Sierra Praeli 2020).

Economic survival

The absence of tourists will take an economic toll on a number of indigenous groups who rely on tourism for their income. Many indigenous communities practise small-scale agriculture, supplemented by hunting for fish and game, and some community members work in the extractive industries. Evidence from scientific research suggests that where there is greater income from outside sources, the communities rely less on the hunting of wild animals for sustenance (De la Montaña et al 2015). Anthropogenic pressures have long since reduced the habitat that sustain populations of species of monkeys, peccaries, tapirs and other mammals, resulting in diminishing supplies of game for indigenous hunters, so that continued hunting of mammals is already unsustainable, as was demonstrated by Zapata Ríos et al in a study of Shuar hunting in 2009.

With the appearance of COVID-19 and the consequent loss of income from tourism, wildlife hunting in some areas of the forest may become more widespread, putting protected species in greater danger of extinction. Some indigenous communities are waiting for the last of the supplies to arrive before closing down until the epidemic is over, which has implications for wildlife populations and the maintenance of game hunting as part of indigenous culture into the future.

Race to the Amazon before shutdown

In the case of the Huaorani – inhabitants of the Amazonian Napo, Orellana, and Pastaza provinces of Ecuador– as with many indigenous communities, fleeing into the forest is one solution for those with precarious incomes in the informal economy who are unexpectedly faced with destitution as a result of government shutdown of the economy. In the forest, survival through hunter-gathering and subsistence agriculture obviates the need of cash. Moreover, taking flight from cities and towns at a time of epidemic has been a longstanding practice for South American indigenous communities, a survival technique passed down from generation to generation (Collyns et al., 30 March 2020).

The dilemma of wanting to return home but fearing being a carrier of the virus is illustrated by the words of Nemonte Nenquimo, leader of the Coordinating Council of the Waorani Nationality of Ecuador Pastaza (CONCONAWEP). When the virus made its appearance in Ecuador, Nenquimo stayed behind in the town of Shell, just outside Huaorani territory, saying she had ‘travelled too much, spoken to too many people and kissed too many cheeks’ over the previous weeks, it was reported by Al Jazeera. It would be too risky to go back to her community now; if she were a silent carrier of COVID-19, it could be devastating to the Indigenous population there. ‘We haven’t heard of any cases in the communities yet, that’s why it’s better to take care and protect them,’ she said. ‘Now, it’s all under control, nobody can enter or leave the territories.’

For those living in voluntary isolation, there is perhaps even greater danger, as their isolation is ever more precarious with the advance of agriculture, cattle ranching, and oil drilling which necessitate the building of roads, which in turn encourages illegal logging. Although not wishing to engage directly with modernity, the Tagaere and Taromenane people of the Ecuadorian Amazon do engage in periodic raids on their more integrated neighbours and cousins, the Huaorani.

As their chances of remaining isolated diminish with the advance of oil exploration and drilling into the Amazon rainforest, their future survival may depend on their agreeing to vaccinations against communicable diseases, a moot point among the various institutions under whose jurisdiction they fall. Where there are no vaccinations available, as in the case of COVID-19, it is even more essential that they be left in peace.

The Sarayaku Kichwa

The isolated communities’ ephemeral hold over their fate contrasts with the experience of the Sarayaku Kichwa of Pastaza province, who have so far been able to manage and negotiate their exposure to the dangers of modernity, but in the case of COVID-19, have found themselves relying on support from local and national government in order to protect themselves.

The 1,200 members of the Sarayaku community live on the banks of the Bobonaza river near Puyo, across the mountains from Guayaquil, the port city where most of the COVID-19 positive cases are located, and where some of the community members work from time to time.

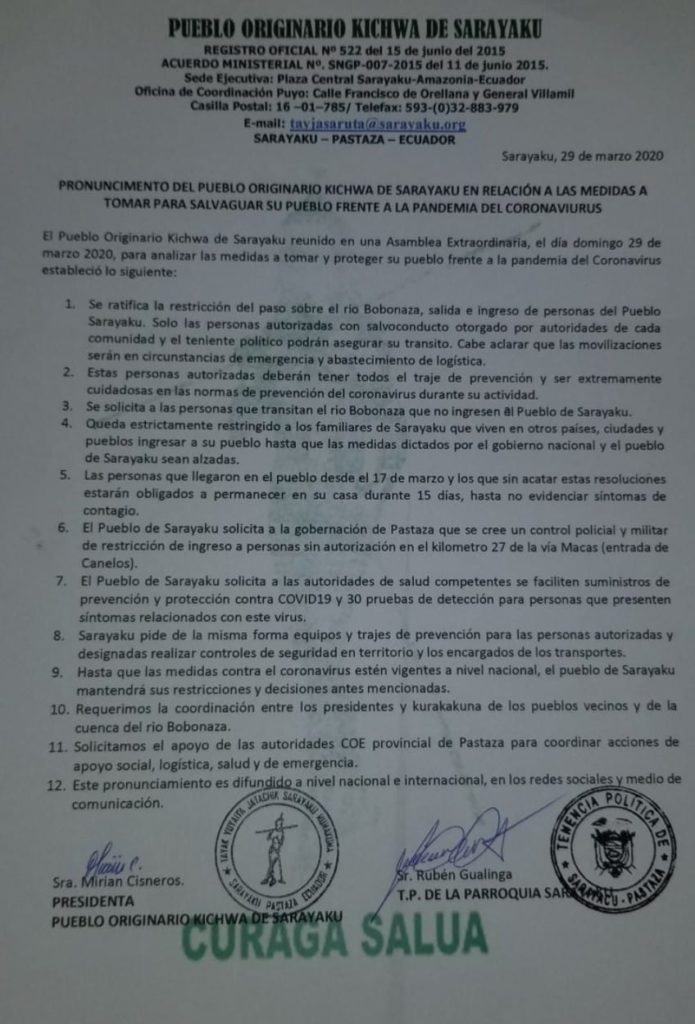

The Sarayaku Kichwa leadership of elders, the Kuracas, held an emergency COVID-19 assembly on 29 March 2020, after which the president of the Sarayaku Kichwa, Mirian Cisneros, and Ruben Gualinga, the political representative, issued a declaration that was posted on 30 March on the Sarayaku Facebook page, Sarayaku Defensores de la Selva (13,987 followers), entitled Pronunciamento del pueblo originario kichwa de Sarayaku en relacion a los medios a tomar para salvaguar [sic] su pueblo frente a la pandemia del coronaviurus [sic] – ‘Declaration of the Ancestral Sarayaku Kichwa with regard to the measures to be taken to safeguard the people in the face of the coronavirus pandemic’, explicitly intended to be circulated on social media nationally and internationally.

The document requests that anyone who arrived in the community after 15 March remain in isolation for 15 days; that the members of the community stay in place except in cases of emergencies; that people passing by on the river – there is no road to the community – do not disembark at Sarayaku. They also request that family members do not return home until the restrictions are lifted. The Sarayaku declared that they would lift the restrictions only when the Ecuadorian government ends the national lockdown. The pronouncement asks the provincial government of Pastaza to close down with a police or military roadblock the road out of Canelos, the town nearest to the Sarayaku Kichwa communities.

In their declaration, the Sarayaku leaders also made a request from the government to supply the community with 30 COVID-19 test kits and protective equipment in case of any suspected cases or outbreaks in the community. They declared their wish to coordinate as part of a collective effort with villages and communities nearby and with the provincial government.

Buen vivir more urgent than ever

The Sarayaku find themselves subjected as ever to the perils of Western civilisation, against which they have fought for 500 years. They continue to advocate their philosophy of sumac kawsay, buen vivir – living in harmony with nature – elaborated by the Uruguayan sociologist Eduardo Gudynas and incorporated into the Ecuadorian constitution in 2008 by former Ecuadorian Minister of Mines Alberto Acosta. Acosta is himself author of several books on Buen Vivir – a way of life that eschews globalised industrial consumer capitalism and aspires to a cessation of global trade and global travel on a large scale. Buen vivir, however, has been long abandoned in practice by the Ecuadorian government that has continued to expand extractive industries geared to exports. It is only now with the global spread of the COVID-19 virus and the prospect of future similar viruses that the necessity to adhere closely to the tenets of buen vivir is more urgent than ever.

References

Acosta, A. (2013) “El buen vivir: sumak kawsay, una oportunidad para imaginar otros mundos.” Icaria: Barcelona.

Brown, K. “Indigenous race into Ecuador’s Amazon to escape coronavirus” Al Jazeera. 26 March 2020. https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/indigenous-race-ecuador-amazon-escape-coronavirus-200325132155853.html

Collyns, D., Sam Cowie, S., Parkin Daniels, J., Phillips, T. “Groups in Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru withdraw into homes as physicians highlight history of diseases ‘decimating’ communities” The Guardian 30 March 2020 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/30/south-america-indigenous-groups-coronavirus-brazil-colombia

De la Montaña, E., R. del Pilar Moreno-Sánchez, J. H. Maldonado, and D. M. Griffith (2015) “Predicting hunter behavior of indigenous communities in the Ecuadorian Amazon: insights from a household production model.” Ecology and Society 20(4):30

Gudynas, E. (2011) “Buen Vivir: Today’s tomorrow” Development 54(4), 441–447

Newson, L. (1995) Life and Death in Colonial Ecuador. Norman and London: University of Oklahoma Press.

Sarayaku Defensores de la Selva Facebook post 29 March 2020

Sierra Praeli, Yvette. “Indigenous people are most vulnerable to the spread of coronavirus in Latin America” Mongabay 30 March 2020 https://news.mongabay.com/2020/03/indigenous-people-are-most-vulnerable-to-the-spread-of-coronavirus-in-latin-america/

Universo, El “Casos de coronavirus en Ecuador marzo 31, 11h00: 2240 contagiados y 75 fallecidos” www.eluniverso.com/noticias/2020/03/31/nota/7800636/casos-coronavirus-ecuador-marzo-31-11h00-2240-contagiados-7

Zapata Ríos, G., Urgiles, C., Suarez, E. (2009) “Mammal hunting by the Shuar of the Ecuadorian Amazon: is it sustainable?” Fauna & Flora International, Oryx , 43(3), 375–385