This article was originally published on the the author’s own website. You can see the original here.

El Salvador ranked 142nd out of 163 countries for Societal Safety and Security in the 2019 Global Peace Index. Nayib Bukele coincidentally became president the same month the report was published. He claimed his victory would be the end of El Salvador’s violent postwar period. However, his methods only perpetuate El Salvador’s cycle of violence.

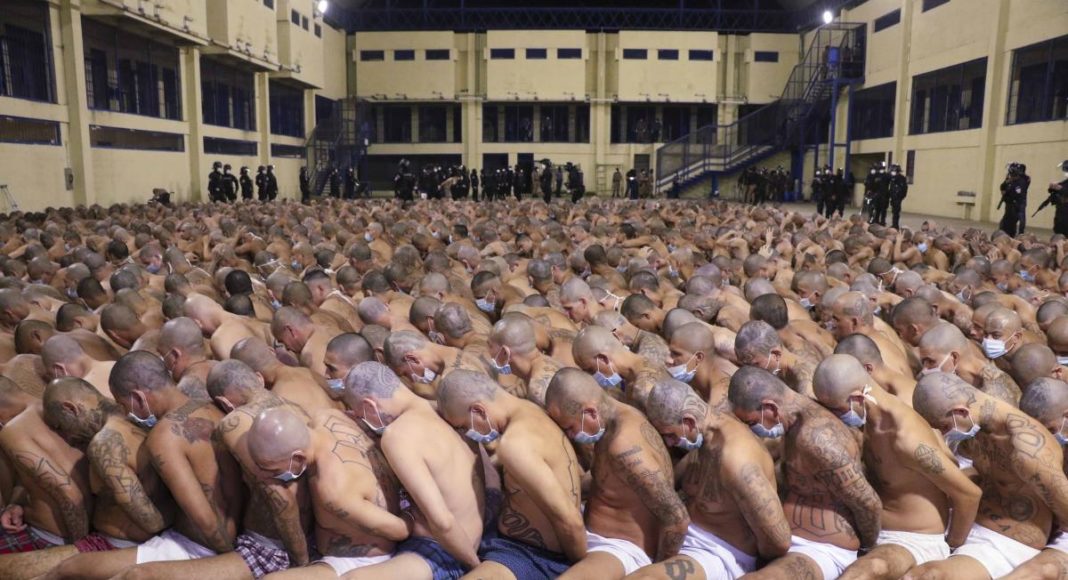

Main Image: Inmates are lined up during a security operation under the watch of police at Izalco prison in San Salvador, El Salvador, on April 25, 2020. © 2020 El Salvador presidential press office via AP.

Look at the photo at the top of this article. No. Really look at it. Absorb it. Let your eyes gather every part of that image. Every tattoo. Every shaved head. Try and count the number of prisoners. Try to imagine what that would feel like, jammed together like boxes in an overcrowded closet, close enough to feel the breath of the person behind you tickling the bare skin of your back.

Have you looked at it long enough? Can you no longer bear to look at it anymore?

Then think about this: that photo is not leaked. That photo was released, publicized, broadcast triumphantly to the world, by President Nayib Bukele and the government of El Salvador to demonstrate their treatment of imprisoned gang members.

Seventy-seven people were murdered in the small Central American nation between 24 April and 27 April. Bukele claimed that the killings were orchestrated by gang members currently incarcerated in the country’s overburdened penal system. In response, he took to Twitter to demand a “maximum emergency in every detention facility holding gang members,” and called for an “absolute lockdown” on imprisoned mareros. The Deputy Prime Minister and prisons director, Osiris Luna, backed up his boss by declaring that “not even a single ray of sunlight will enter any of these cells.”

The new standard of prisoner treatment in El Salvador is in direct violation of UN resolutions regarding humane treatment of prisoners. There are 38,000 prisoners in El Salvador; the prisons only have a capacity of 18,051. Cramped conditions have facilitated the spread of tuberculosis and contributed to a rise in mental health issues. The measures come into effect at a time when El Salvador, like the rest of the world, is combating the spread of the novel coronavirus. Any outbreak in the Salvadoran prisons is likely to prove catastrophic.

And the government is proud of what they’ve done.

There is a demon in El Salvador, and his name is Violence. The demon must be a he, for the way he acts is deeply imbued with masculinity, power, and oppression. He is endemic, ubiquitous, omnipresent. He has been there for centuries. He was there when the Spaniards introduced cold steel to the Mesoamerican peoples by demonstrating its brutal power at the end of a sword. He was likely there even before that, when the gods demanded blood in exchange for goodwill and protection.

He is cunning, this demon. He knows we recognise him as a demon when he dresses in black. He knows we see the violence of the Salvadoran gangs; he knows we recoil at the brutality and disregard for human life and demand answers, reforms, punishment. So he comes to our aid as a demon dressed in white, telling us that the violence of the government will end the violence of the gangs. He dies so that he may yet live again.

The demon has died once before, at the end of the Salvadoran Civil War. Seventy-five thousand people lost their lives in that conflict; over half a million fled the country. Right-wing death squads–some funded by the United States–stalked the urban streets. Left-wing guerrillas patrolled the jungles. Both sides committed atrocities including rape, torture, and mass killings. It seemed like Violence’s grand finale. In 1992, the two sides came together to sign the Chapultepec Peace Accords. The left-wing Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (FMLN) transitioned from a guerrilla movement to a legitimate political party, ushering in a period of political stability that has largely remained intact.

But our demon was smart; he laid the seeds of his own rebirth in the civil war. Many Salvadoran refugees settled in Los Angeles in the 1980s and 1990s, where they were targeted by other ethnic groups and gangs in the city. They formed gangs of their own to help protect themselves from rival ethnic communities and local law enforcement. Two of the strongest were Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and Barrio 18. Exposure to street gang culture and the US penal system turned many Salvadoran refugees into hardened criminals.

After the signing of the peace accords, the United States began deporting Salvadorans with criminal records. Members of MS-13 and Barrio 18 arrived back home to find a country broken by war. Economic opportunities were nonexistent; security forces were undermanned and underfunded; and bonds between and within local communities had decayed and collapsed. In this vacuum, the gangs began to grow in numbers and in strength. The demon in black was born.

Now, he is everywhere. Journalist Tariq Zaidi estimates that there are 60,000 gang members in El Salvador. A report by the International Crisis Group states that the gangs are active in 94 per cent of El Salvadoran municipalities. News correspondent Miguel Patricio reports that some 600,000 Salvadorans live off the proceeds of gang activity — a number amounting to some ten per cent of the population.

But it is not much of a living. Salvadoran community leader Reverend Gerardo Mendez told NPR that gang members “still live in the same neighborhood, they still go hungry, they have no luxuries.” Most gang members live on less than $250 per month. Nor are the gangs motivated by any sense of political ideology. Gangs have taken money from both ARENA and FMLN, the two major political parties in El Salvador, in exchange for votes in presidential elections.

Rev. Mendez told NPR that the gangs fight for identity above all else. MS-13 and Barrio 18 have long been rivals; the hatred between the two is so strong that members of MS-13 won’t deign to say the number eighteen. But there is little difference between the two gangs in ideology or practice. Barrio 18 is more transnational, with members in nearly every Central American country, but within El Salvador both gangs are predominately Salvadoran.

The gangs don’t fight over their identity; the fight is their identity. The violence exists as a rationale unto itself. It is not a tool of the gangs; it is their purpose. Every action is taken in order to perpetuate violence. The demon must be fed.

The violence permeates every facet of life. Many gang members come from abusive families; they meet the demon at an early age. Even for those with healthy home lives, the violence is unavoidable. In 2015, El Salvador averaged more than seventeen murders per day. A survey conducted by the UN Refugee Agency from the same year found that 62 per cent of female refugees directly witnessed violent activity. The same percentage reported seeing dead bodies; some claimed to see them on a weekly basis.

Gangs are petty tyrants, controlling their destitute neighborhoods with a bloody fist. They are obsessively territorial; visitors often have to flash their car lights to indicate allegiance to the gang in control of that neighborhood before entering. In 2015, a 15-year old girl named Marcela was shot and killed at close range because she sold tortillas in one neighborhood, but lived in another. Dead at fifteen, all because she was on the wrong side of the street.

The gangs are the poor robbing the poor. It is not about acquisition of wealth; it is about the feeling of power, of control, of total dominance, that only violence can provide. The extortion rackets run by both MS-13 and Barrio 18 are not tools to create profit, but a means to rationlize their violence.

Rita, a Salvadoran woman, sold pupusas out of her house in Chalatenango. Soon after she began, members of Barrio 18 arrived. “First they came and demanded two dollars, and I was afraid to say no,” Rita said. “Within a week they were back and said I had to pay $10 a day.” Rita refused to pay. In retaliation, eight men from Barrio 18 raped her daughter. She had just left the house to collect water from the nearby water pump.

Sexual violence is pervasive. Women don’t leave the house alone at night. Most go without makeup for fear of catching the eye of one of the gang members. For the mareros, “women are objects to be used and discarded,” says Rev. Mendez. “A gang member can kill his woman for the smallest detail or suspicion. He can easily beat her to death and pick another girl.”

No one is safe from the depredations of the demon. Norma, the wife of a police officer in El Salvador, was extorted by MS-13. When she refused to pay, she was attacked by four mareros. “Three of the four of them raped me,” she told UNHRC. “They took their turns…they tied me by the hands. They stuffed my mouth so I would not scream. They took off my clothing. They then threw me in the trash.”

Norma and her husband filed an official report. It did little good. Few Salvadorans trust the police. Some see them as incompetent and unable to offer protection from the gangs. Others believe the incompetence is purposeful. “The police and the maras work together,” one Salvadoran woman told UNHRC. “It’s useless to go to the police. They let everyone go after 48 hours. If you call the police, you just get into more problems.”

The demon in black is winning. Gang violence has broken Salvadoran society. There is no trust between citizen and government. There are few communities that feel wholesome and secure. They live in fear of violence; it is all they know.

But it does not have to be this way. The demon can be defeated. Both gangs have at one time offered ceasefires to the Salvadoran government. A survey of 1,200 Salvadoran gang members conducted by Florida International University found that almost every marero thought of leaving the gang at some point. There is a way forward. It will not be easy – exorcisms never are – but El Salvador does not have to remain locked in this cycle of violence.

Three major steps need to be taken. First, police forces at the local and federal level need to rebuild trust with their communities. Salvadorans need to know that they can go to the police to help solve their problems and address their grievances, particularly those related to gang violence. Police forces must be able to ensure safety to anyone filing a complaint or an official report. Citizens will not report a crime if they fear retribution at the hands of the mareros.

Building a more demonstrably effective police force is a good place to start. According to La Prensa Gráfica, impunity rates for homicides reached 95 per cent in 2014. Bringing criminals to justice will show communities that the police are there to serve and protect the people, not the gangs. It should go without saying that such measures only work if arrests are accurate and evincible; the people arrested must actually be guilty of the crimes at hand.

Second, the government must improve rehabilitation programs to offer a path back into society for gang members. Most incarcerated gang members lack employable skills. According to a report by the International Crisis Group, 80 per cent of gang members have never held formal employment, and 94 per cent have no secondary education. Prisons should be viewed as centres of rehabilitation rather than punishment; incarcerated gang members should partake in training programs and employability courses so that they can earn a living outside of the mara upon their release.

Rehabilitation programs must focus on reforming the man, not the worker. There is a strong stigma in El Salvador associated with gang membership. Many of the gang members had troubled upbringings; nearly all have had traumatic experiences while involved in the maras. The gangs are social networks as much as they are criminal enterprises. Reformed gang members must have the skills necessary to succeed socially as well as professionally upon their release.

Finally, and crucially, local and federal officials must work to address the underlying causes that feed the maelstrom of gang violence. They must invest in improving local communities. Maras largely operate in poorer sections of El Salvador, where job prospects are grim and poverty rates are depressingly high. The bare necessities of food, shelter, and clean drinking water sometimes go unfulfilled here. In these dire situations, membership in a gang can seem the only reasonable way to provide for one’s family. Alternatives must be put forward; young people must be able to earn wages and provide the necessities for their families without resorting to crime. Investment in infrastructure and small business-friendly loans, coupled with effective security strategies to protect those investments from the gangs, is a good place to start.

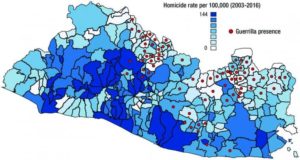

Investment of a different sort must be made in restoring social cohesion to local communities. Communities with stronger kinship networks are less likely to become hotbeds of gang activity. There is an intriguing inverse correlation between gang activity today and guerrilla activity during the civil war. Guerrilla movements rely on close social cohesion to operate effectively; that cohesion seems to remain today. Areas where the guerrillas were more active in the civil war have lower homicide rates and less gang violence on average than places controlled by government forces during the war. Local community leaders, particularly religious leaders, should emphasise stronger ties within communities as a way to cut off oxygen to the fire of gang violence.

Investing in education and protecting schools from the depredations of gang violence are the single best way to improve local communities, both socially and economically. In 2017, some 25 per cent of Salvadorans between the ages of 15 and 24 were neither working nor studying. Education provides building blocks for future growth intellectually and professionally, and schools offer safe and productive opportunities for socialisation. Schools allow children the opportunity to create healthy social relationships today and acquire the skills to succeed tomorrow. They are the nearest thing to a silver bullet that El Salvador has.

But successive governments have demonstrated their fondness for steel bullets rather than silver ones. In 2011, 44 per cent of the security budget was invested in the police and justice ministry. Thirty-one per cent was invested in the judiciary. Just one per cent was invested in crime prevention and rehabilitation. The purpose of fighting crime, according to the Salvadoran government, is not to fight crime. It is to fight.

Sound familiar? It should. You’ve met this demon before. You’ve seen him in black; now, he appears in white. Salvadoran governments promise to end gang violence through mano dura (iron fist) policies, but in doing so they promote destructive practices of state violence. The cycle continues. The demon dies, so that he may yet live again.

Mano dura has been the standard operating procedure for Salvadoran governments since President Francisco Flores announced the plan in 2003. Despite the stark ideological differences between the two parties, mano dura is the primary anti-gang platform for both ARENA and FMLN. They say it is the only way to fight the gangs. But it’s been in place for seventeen years, and the gangs are still here. One official admitted that the government was “fighting a war they cannot win.”

But still they fight. Arrests run into the thousands, often without evidence. Young people living in gang-infested territories are frequently beaten and detained despite having no gang affiliation. The grander the violence, the better. In recent years Salvadoran police forces have launched more armed raids on gang territories, leading to direct firefights between the police and the gangs. If an innocent bystander catches a stray bullet, well, the demon must be fed.

Sometimes the gangs are given a fighting chance; sometimes they aren’t. In 2016, reported firefights between police and gangs saw 96 per cent of the casualties on the side of the gangs; just one per cent were police officers. James Cavallaro, a commissioner of the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights, says that number cannot be accurate. “The truth is that the proportion of people killed – when it comes to real confrontations – can be more or less two or three times more civilians than police, depending on the training that is supposed to be higher when it comes to a police officer.” In El Salvador, the ratio is 59 civilians to one police officer.

Extrajudicial killings are on the rise. According to a US State Department report, there was one potential extrajudicial killing by police officers in 2013. There were 41 in 2016 alone. An exposé by Revista Factum uncovered private conversations among forty police officers regarding extortion, torture, and execution of suspected gang members. Ten per cent of the women interviewed by UNHCR said that police officers or other security forces “were the direct source of their harm.”

It is unclear whether these inhumane violations are products of their own initiative, or directives from higher levels of government. What is clear is that the government is under no pressure to change their ways. Mano dura is popular. In a 2017 survey, 40 per cent of Salvadorans approved of torture as a crime fighting technique. Thirty-four per cent said the same of extrajudicial killing. Governments see no reason to address the root causes of gang violence with unpopular policies that may not prove effective in the short term. They prefer instead to give a free hand to security forces to combat the gangs, bask in the adoration of the people, and silence critics who complain about human rights and atrocities of violence.

That is clearly the strategy of the current president, Nayib Bukele. He promised to improve security in the country upon his election to the office in June 2019. He threatened military action against the Assembly after the legislative body moved lethargically on a $109-million loan for enhanced security programs. Bukele later backed down, claiming that God “asked him to be patient with the politicians.”

Bukele is flexing his authoritarian muscles. He has pushed through aggressive measures to contain the COVID-19 pandemic–measures which have been called unconstitutional by numerous observers. He has been warned about human rights violations by both Amnesty International and the World Organization Against Torture. Bukele does not care, claiming that human rights defenders want “the death of Salvadorans.” Observers are growing concerned. A recent editorial in El Faro claimed that “it has become common for the Nayib Bukele government to try and silence any truth that contradicts it and blames others for its inability and mistakes.”

“These days,” the author continued, “it’s evident the citizens fear the arbitrariness of the Police more than the risk of contagion.”

Fear. The demon of violence loves fear, whether he’s dressed in black or white.

Scroll back to the top of this page. Look at that photo again. See there, in the foreground, our demon of violence, dressed in black. Shoulders slumped, head down, incarcerated, he fears his time is near an end. That is something to be celebrated.

But wait. Look beyond that. See those blurry figures in the back, guns at the ready? Our demon of violence, dressed in white. He is poised for a rebirth, violence extinguished becoming violence reborn. He might be dying; but he might yet live again.

Scott Wagner is a freelance writer based in the US, writing about current affairs, politics, and sport.