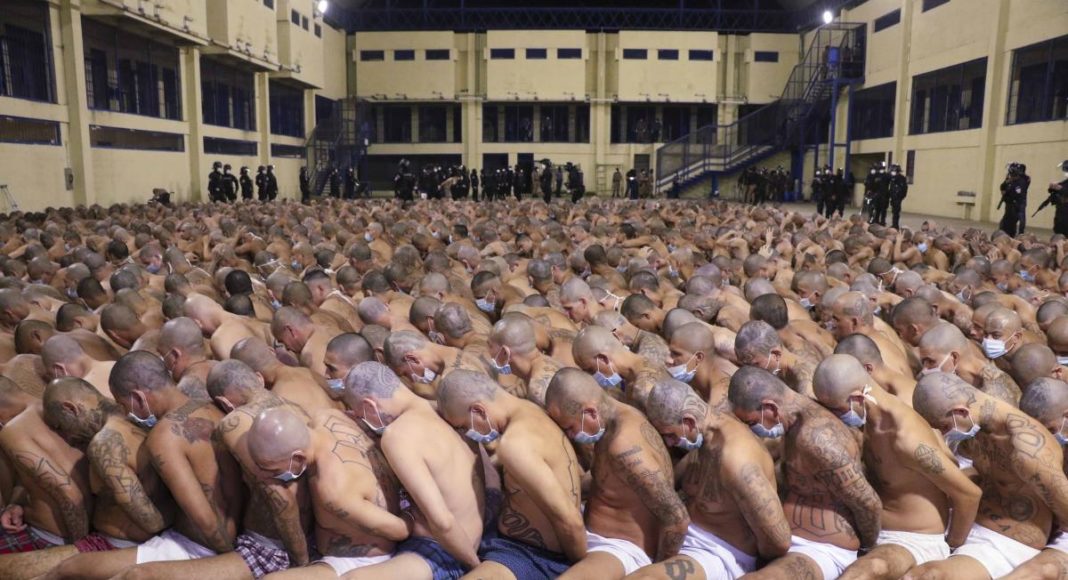

Between the 24 and 27 April 2020, 76 gang-related murders were reported in El Salvador – a significant hike from the 65 murders which took place across the country in the previous month. As a reaction to the bloodiest few days that El Salvador had seen for a while, President Nayib Bukele authorised a 24-hour lock-down of prisons and sent gang leaders into solitary confinement. Salvadorian security forces were authorised to use ‘lethal force’ against gang members in the country, and images were published of inmates grouped together – breaking current social distancing guidelines – whilst guards searched their cells.

This spike in murders comes after a strange few months in El Salvador. Human Rights Watch recently warned of the dangers of the country becoming the next dictatorship in Latin America. Bukele has been accused of ignoring and intimidating other branches of government and violating human rights – moves that have led organisations such as Amnesty International and the World Organization Against Torture to issue warnings to Bukele.

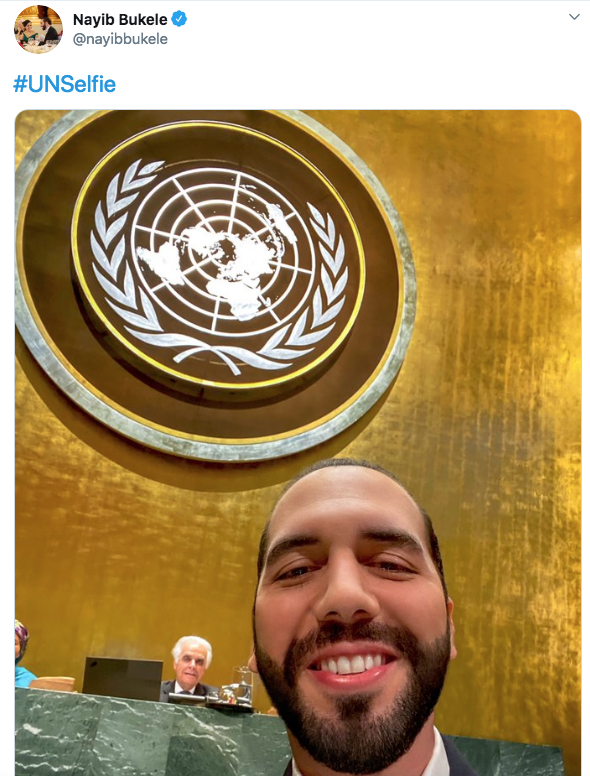

So, how has the trendy, young, social media-savvy leader – who gained attention by taking a selfie at the UN General Assembly and whose popularity reached 91 per cent after assuming office in June 2019 – come to be accused of having authoritarian tendencies and undermining democracy?

The outsider

Nayib Bukele, 38, is the former mayor of the capital San Salvador. He was elected president in 2019, the first holder of this office not to come from either FMLN or ARENA, the two political parties that have held the presidency since 1989. After his landslide victory, Bukele promised a ‘new era’ for El Salvador and said he would fight corruption and improve security.

A turning point came in February 2020 when armed soldiers marched into the country’s Legislative Assembly as Bukele appeared to give his political deputies an ultimatum – either approve a loan of $109-million to finance his security program or face similar military action the following week. He also threatened to invoke Article 87 of the Constitution, which authorises action to ‘re-establish constitutional order’. Bukele also claimed that God had asked him to be patient with the politicians.

Bukele and his party, GANA, have a minority in the Assembly and both FMLN and ARENA politicians questioned the funding request, arguing that it was not clear where the funds would go, and called for more time to study the proposal. Bukele called this an insurrection and accused politicians of the two largest parties of not caring about the country’s security.

In a strongly worded editorial, El Faro (a Salvadorian online newspaper) said Bukele had ‘laid to rest the last doubts about his character: he is a showboating populist, anti-democratic, and authoritarian. With the cheapest tricks – vile, dangerous and claiming he has God on his side – he turned over a dark page in the history of our young democracy.’ Sonja Wolf, an expert on El Salvador at CIDE University in Mexico added, ‘his popularity is making him a little arrogant.’

Draconian enforcement of the Covid lock-down

The coronavirus pandemic emerged amidst this strained political atmosphere. El Salvador reacted to the crisis earlier and more strongly than others in Central America. The Ministry of Health declared a national health emergency on 23 January 2020, however Bukele took direct control of containment efforts in early March.

Responses have included a 30-day quarantine for those entering the country, the closure of borders and a domestic lock-down imposed on 22 March, where it was only permitted to leave the house to buy food. As of 3 May, 28,500 tests had been carried out in El Salvador, with 490 confirmed cases and 11 deaths.

Those breaking the lock-down have been detained and held in containment centres for 30 days. However, questions exist over the legality of arresting citizens for breaking quarantine measures and there were reports of people being detained arbitrarily and with excessive force. The Salvadorian Supreme Court ruled that such action was unconstitutional, and the Legislative Assembly also announced that it did not approve of the measures. In the first month of the quarantine, the country’s Human Rights office received 778 complaints of violations stemming from arrests for breaking lock-down rules.

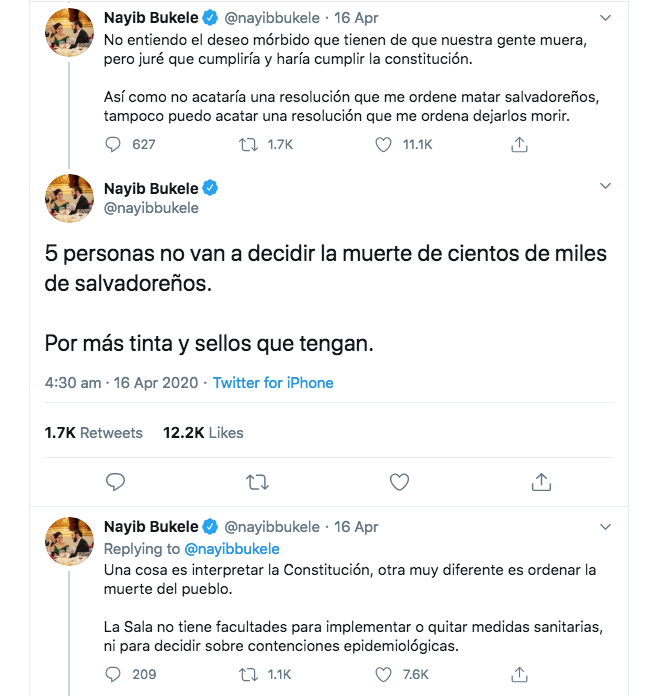

However, Bukele ignored these rulings and accused the five Supreme Court judges of trying to kill their compatriots. When a TV report from the coastal town of La Libertad showed strict lock-down rules being broken, Bukele ordered entry routes into the city to be blocked and the city’s businesses to shut for 48 hours. Since then, the country’s Chief Prosecutor has declared that they are investigating whether this move, too, was unconstitutional.

International responses

Jose Miguel Vivanco, Head of the Americas Division at Human Rights Watch said ‘Bukele acts as if Covid-19 justifies removing the Supreme Court’s critical role as a check on rights abuses by the executive branch.’ In addition, Bukele vetoed a law brought by deputies in the Legislative Assembly to protect the human rights of citizens during the pandemic and to regulate the application of the quarantine. In response to HRW, Bukele invoked ‘constitutional order’ to validate the veto on Supreme Court review, claiming to be acting in the public interest.

This coincided with the recent hardening of policy against and followed reports that gangs had initially helped to enforce the lock-down in El Salvador. Erika Guevara-Rosas, the Americas Director for Amnesty International, argued that Bukele’s decision could lead security services to commit human rights violations and would make social distancing hard or impossible to enforce in these circumstances. The latest moves built on the already tough ‘mano dura’ measures imposed by Bukele, such as mixing members of rival gangs in the same prison sectors and blocking phone and Wi-Fi signal for inmates.

The people’s leader?

ABC in Spain reported that only 8 murders were recorded on the first full day (28 April) after the harsh measures were introduced and recent figures from the Salvadorian government indicate there were 441 homicides between January and April this year, down from 1,059 in the same period last year.

It is important to highlight, too, that Bukele remains one of the most popular leaders in Latin America. He receives significant support on social media and, in mid-April 2020, a CID Gallup poll of 1,200 Salvadorians suggested that 97% supported how Bukele was managing the pandemic, 93% approved of his work as President and 98% had a positive image of him as a person.

Main image: Inmates are lined up during a security operation under the watch of police at Izalco prison in San Salvador, El Salvador, on April 25, 2020. © 2020 El Salvador presidential press office via AP