Adam Isacson has worked on defence, security, and peacebuilding in Latin America since 1994. He now directs WOLA’s Defense Oversight program and just returned from his first visit to Colombia in nearly two years. Here are some of his reactions after having met a wide variety of officials, activists, and experts. This article originally appeared on Adam’s website.

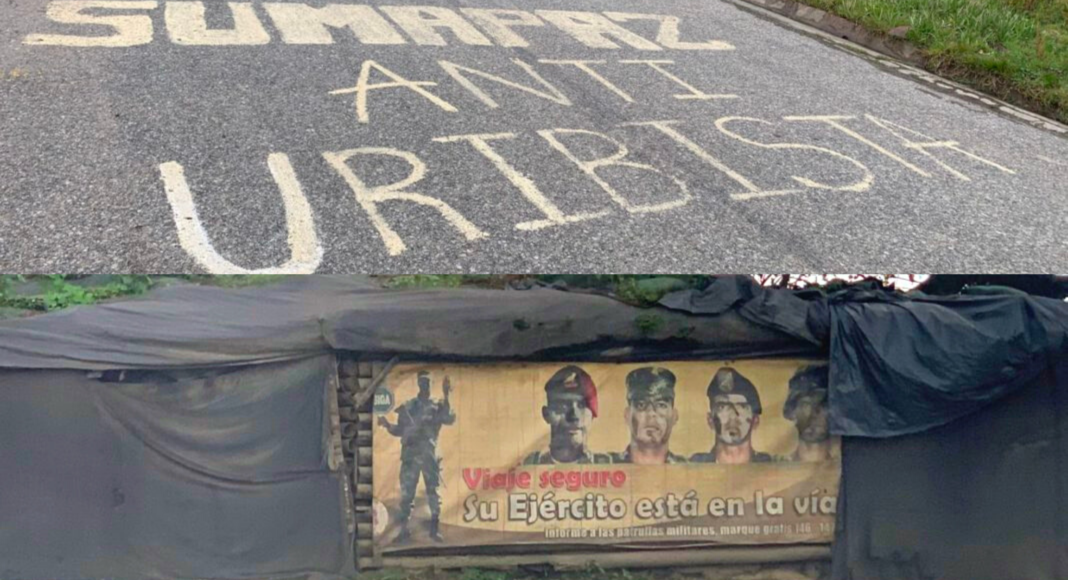

I spent October 3-9 in Colombia, flying back on the 10th. Most of the time, I was with a member of Congress, Rep. Jim McGovern (D-Massachusetts), and his staff. We went to Cali, a city still reeling from intense protests and the security forces’ vicious response. We went an hour and a half south of Cali to Santander de Quilichao, in the north of the department of Cauca, which leads all of Colombia’s 32 departments in killings of social leaders and of demobilized ex-combatants. We went to Bogotá, of course, and to the formerly guerrilla-controlled Sumapaz region about 2 1/2 hours’ drive south of Bogotá.

Traveling with Rep. McGovern meant having access to a wide variety of officials, activists, and experts. This was my first chance to visit Colombia for nearly two years, as I didn’t travel during the pandemic.

Here are eight reactions that are really fresh in my mind upon returning. These aren’t final, comprehensive, or necessarily backed up by hard data. These are my reactions, not necessarily those of the organization I work for or the people I traveled with. Some of them are just feelings or impressions. But they are strong impressions, and I am disturbed by them.

1. Even putting human rights concerns aside, Colombia’s security forces are in retreat. There is a notable territorial pullback in many parts of the country. Once you pass the last Army checkpoint, you’re on your own: everything after that is effectively ceded to illegal armed groups. These days, that last checkpoint is often quite close to population centers or the main road. After that, people plant coca while armed groups put up their banners and enforce their own sets of rules with a remarkable degree of freedom. I can’t remember feeling such a sharp security pullback since the Samper presidency in the mid-1990s.

2. Some of this is because of COVID: the government has very few resources right now (or is unwilling to seek enough revenue from its wealthiest citizens). In February 2020, just before the pandemic hit, only 15 of the Colombian army’s 42 Black Hawk helicopters were reportedly functioning. Even if that particular situation improved (I don’t know if it did), the pandemic depression has likely hollowed things out further—and civilian ministries are probably in even rougher shape.

3. In government-abandoned territories, community leaders don’t know what to do or whom they should be dialoguing with to protect themselves. When the FARC existed, and ungoverned spaces tended to be under a single illegal group’s uncontested control, at least the rules were clear. There were local commanders to whom communities could appeal when a group’s fighters became too abusive or its norms became too onerous. Now, though, there are often a few small, overlapping groups—the ELN, ex-FARC dissidents, “Gulf Clan” paramilitaries, single-region armed groups, mafias—with constantly shifting territorial control, alliances, and divisions. Caught in the middle, civilian communities don’t know whom they should even be talking to.

4. Community leaders can’t publicly ask for the government to be present in their territories. That would be suicidal: retaliation from armed groups would be swift. The most they can call for is a “humanitarian accord” in which all armed actors agree to some degree of restraint in their actions against civilians. Though it’s hard to envision how to compel armed actors to honor them, humanitarian accords offer the best hope for protection in a situation of statelessness and abandonment, and communities’ proposals deserve support.

5. Armed groups’ aggression against civilians seems more common than their combat with the security forces. Though of course there are ambushes and attacks, today’s small, fragmented armed groups prefer not to initiate combat with the military and police. In fact, we heard that local-level cooperation from security forces is ever more common, especially along trafficking routes. This is due to corruption, but also to incentives: who wants to give their life fighting a small local band that poses no existential threat to the state, and that most Colombians haven’t even heard of?

6. People are afraid of their own security forces. Between the April-June paro nacional protests and violent forced coca eradication operations in rural areas, the military and police have been very hard on civilians this year, killing dozens and wounding or torturing many more. Body counts aren’t a measure of anything, but the number of armed and criminal group members that the Defense Ministry reports as killed or “neutralized” this year is greater—but not wildly greater—than reported killings or wounding of civilians. “Today, the war is the government against the peasant,” a coca farmer told the New York Times a couple of weeks ago, and I heard similar last week. I’d add, though, that the armed groups have also declared war on the civilian population, and the security forces are usually nowhere to be seen. Meanwhile, in places like Cali, people who participated in protests are terrified. We spoke to people who were wounded, or who suffered torture in police custody, but are afraid to come forward and publicly denounce what happened to them.

7. Human rights defenders are in bad shape. Longtime colleagues—lawyers, national ethnic organization leaders, campesino activists—are exhausted. They looked and sounded terrible, like asylum lawyers I interviewed at the U.S.-Mexico border at the worst moments of the Trump administration. Some broke down in tears. It was painful for them to recall the hope they felt in 2016-17 when the peace accord held a promise of tranquility and progress. For them, Colombia has taken a giant step backward from that hope—way farther back than I’d been led to believe before visiting.

8. We’re doing old-fashioned human rights work again. For several years—from the latter moments of the FARC peace negotiations until quite recently—we had the luxury of advocating “state presence,” “crop substitution,” “rural reform,” “land restitution,” “restorative justice” and similar proposals typical of a country leaving a bitter history behind. Not anymore. There are too many new victims: victims of violence at the hands of state actors, displaced and confined communities. Too many people left unprotected. Sure, even during the more hopeful late-2010s period we were documenting unpunished murders of social leaders and ex-combatants. Now, though, the crisis feels more generalized, happening in both rural and urban areas.

Many thanks to Rep. McGovern and his staff for taking this initiative to visit Colombia, to accompany its human rights defenders and victims, and to encourage the U.S. and Colombian governments to change course. I’m really glad they came, because this is a desperate time.

Colombia already had a plan for avoiding the outcome I’m describing here. It’s laid out in the 2016 peace accord. Despite the present desperation, and even though the U.S.-backed government rarely invokes it, the accord’s development, protection, reintegration, victims, and justice provisions continue to point to the best way forward. The hour is getting late, but it’s still possible to implement that accord.