This massacre of hundreds of innocent Salvadorans was lost to history for 20 years. But even after another 20 years no-one has faced justice for it and parents still remain separated from their children.

In 2001 a priest encouraged some campesinos in Usulután, El Salvador, to remember the massacre at El Mozote. They replied, ‘What about our massacre?’ – another massacre from the same period which the priest knew nothing about. Thus began the telling of the story of Quesera. Local people shared their memories, an Argentinian forensic team came to investigate the massacres at Quesera and Mozote, memorial services were held, monuments were built, and US art volunteers helped the process.

For 20 years Quesera had not been part of the first draft of history. Some of the violence of the decade long civil war, like the murder of Archbishop Romero, the El Mozote massacre, and the murder of six Jesuit priests were widely reported at the time. The El Salvador Truth Commission of the 1990s was a significant attempt to write history but Quesera was one event that was not included.

So during the early 2000s the story of the Quesera Massacre started to be told, and in April 2007, I came with a group of visitors to a memorial service at the Loma del Pájaro, a hill in the centre of the area of the massacre.

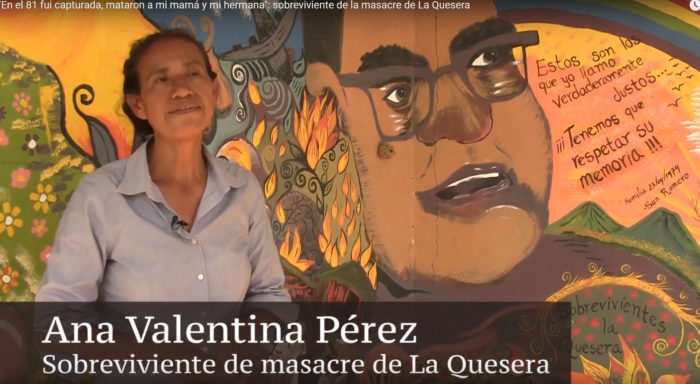

One of the survivors was willing to be interviewed, and I made a short film. It was screened at the El Sueno Existe Festival a few months later, and was one of my first uploads to a recently established platform called Youtube.

Even today, 40 years later, establishing what happened at Quesera in 1981 is not easy. Estimates of the numbers killed range from 300 to up to 1,000, with most settling at around 500. It was a series of killings over several days, 20 to 24 November, according to the memorial I filmed, longer in other sources. Quesera is just one of a number of villages attacked.

Army action around Quesera may have been a reprisal for the destruction by the FMLN of the strategic Puente de Oro on 15 October, itself a sign of the extent of guerrilla activity, and which cut the key Pacific coast highway linking San Salvador to the east of the country. However, the killings were part of a wider scorched earth approach adopted by the Salvadoran military at that time.

Any campesino in the wrong place could be treated as guerrilla supporter, and be shot, tortured or disappeared. The main, but not the only, army unit involved was the US trained Altacatl Batallion, formed in March 1981 and a key player in many other massacres including El Mozote a few weeks later.

A 2016 study documenting the scale of what it called the lost case of genocide in El Salvador, helps to set the context for Quesera. It identified 184 massacres that killed nearly 8,000 people. Although they continued throughout the war, the early years saw the most killing. Seven massacres involved the killing of more than 300 each, all between 1980-2, and in Quesera and three others between 500 and 800 people died.

This study’s source for Quesera, led me to a US court document dated 2012, an expert witness report in a court case concerning the Salvadoran Minister of Defence during 1979-83 General García-Merino. Many pages detailed his time as minister and the role of the military at that time. An appendix listed 59 massacres, with Quesera at No 32, one of five with at least 500 deaths. The description of events at Quesera stressed the particular cruelty to children during this massacre. And it included a reference to the film I had posted on YouTube years before. Following this case the general was deported from the US back to El Salvador.

The report also cited a request from Tutela Legal, the legal and human rights defence organisation of the Archbishop of San Salvador, for a legal investigation into the massacre, dated January 2007, just a few months before my visit. It identified the places where the killings took place, named nine senior officers involved, and noted that 41 bodies had been exhumed and 14 identified. It also described this massacre as involving sadism ‘without limits’, and spelt out why the amnesty law of 1993 did not apply. Progress was slow, not helped when the Archbishop closed down Tutela Legal in 2013, saying it was time to put conflicts of the past behind.

The Unfinished Sentences Project based at the University of Washington, helped the legal process in Salvador when it was able to reveal the role of the USA through the release of diplomatic cables. Documents released since 2015 show an Embassy then trying to rein in a murderous regime. One reports a US helicopter passenger witnessing indiscriminate firing on civilians, this on 17 October 1981 the week before the Quesera massacre.

Others show concern about comments by Archbishop Rivera about the massacre, and the Ambassador’s attempts to moderate them. Just after the massacre, in a cable headed ‘Some tough talking with Garcia’, the Ambassador notes that it is ‘ …disturbing to have detailed secret reports of the Salvadoran military massacring women and children along the Rio Lempa ..’ And over breakfast on 10 November he learnt that two of the Foreign Minister’s bodyguards had lost brothers in the sweep and were unable to find their bodies, and that a fellow police officer was said to be repelled by the violence. The Ambassador hoped that the Minister might help to avoid a repetition.

In a 2015 report, a task force at the University of Washington documented civil war massacres. It noted that at Quesera some 2,200 troops were involved in the killing of 350-500 people, most of them women and children, the disappearance of 36 women and 24 children, and the displacement of another 1,000 people. The report suggests that this massacre was more systematic that previous previous military actions, with artillery and air attacks and the attempt to kill everyone in this locality considered to be ‘the enemy’.

The 1982 Truth Commission received information about over 5,000 missing people, but its report said little about children who survived. Pro-Búsqueda is an NGO founded in 1994 to re-unite children and families separated during the Civil War. It has documented nearly 1,000 cases, with many still unresolved. Some children were passed to the Red Cross, and there have been suggestions of the military running an adoption racket, but it is hardly surprising that where a scorched earth policy was being implemented, protection of children was ignored.

In 2011 Pro-Búsqueda asked the fiscal office of Usulután to help find the missing children of 11 Quesera families. From these and subsequent requests Pro-Búsqueda has reunited five Quesera families. Three were found in France, the others in Belgium and the United States. A film produced by Unfinished Sentences in 2015 suggested that 24 children disappeared during the Quesera massacre and were then unaccounted for.

In a key decision in July 2016, Salvador’s Supreme Court declared that the amnesty law of 1993 was unconstitutional, adding that the statute of limitations did not apply to crimes against humanity. This was followed with local Judge Jorge Guzman reopening the Mozote case and seeking evidence from the military. Progress in this better known case gives an indication how far past crimes like Quesera may be tackled. In 2019, Guzmán ordered the military to open its archives but inspections scheduled at eight locations during September-November 2020 were blocked. By this time a retired Air Force General, one of nine named in the Quesera case, admitted that the Mozote massacre was carried out by the military, though he denied any personal involvement.

The Government has set up commissions to search for disappeared adults (CONABÚSQUEDA) and children (CNB). Recent posts on CNB’s facebook page

have celebrated 10 years of operational work, and invited anyone with information to make contact.

While legal action and searches for the disappeared have continued the political scene in El Salvador has changed dramaticaly. Nayib Bukele, born a few months before the Quesera massacre, campaigned as ‘the first post-war President’, saying he would open archives as ‘the only way to heal the wounds of the past is for the truth to be known.’ After actions since his election belied these promises, with access to military records refused in 2020. Then in August 2021 Bukele’s party passed a law requiring all Judges over the age of 60 to retire. Judge Guzmán is 61. However later in August, on International Day of Forced Disappearances, Bukele’s Vice President, Felix Ulloa, reiterated his commitment to victims of the civil war. It is now 40 years since the Quesera massacre. Though some of the story has now been told it still casts a long shadow. Justice for this crime against humanity is still awaited, and children are yet to be united with the families they were taken from many years ago. El Salvador’s military records remain closed.