This year on Peruvian Independence Day many took to the streets in the ‘Tercera Toma de Lima’, rather than celebrating. Natasha Tinsley reports from the capital on what Peru is fighting for.

Military salutes shake the centre of Lima as President Dina Boluarte makes her way to the ceremony at the cathedral. Cloudy sky and mild air, it’s a typical Andean winter morning. Being 28 July, it’s the Day of Independence (Fiestas Patrias), yet the stale atmosphere in the Peruvian capital this year is far from the norm.

A few blocks away, a local gentleman admires typical Peruvian delicacies at an open-air market. There are king kongs (Lambayeque cake), galletas ‘paciencia’ (lemon biscuits), suspiros limeños (meringues), and alfajores de maicena (cornstarch shortbread). ‘Can’t we even walk around the centre?’, he chuckles to the stall owner about the road closures. ‘It’s all shut until the president finishes her speech’, the owner responds, rolling her eyes, ‘Whatever will she come up with this time?’.

Nearby market-goers join in on the joke and, as usual, mistrust in the government is taken lightly. But when the sniggers begin to trail off, the limeños’ eyes set with panic. Today should be different. Festivity and patriotism, not tension and division, should be taking the front seat.

What are Fiestas Patrias and the Tercera Toma de Lima?

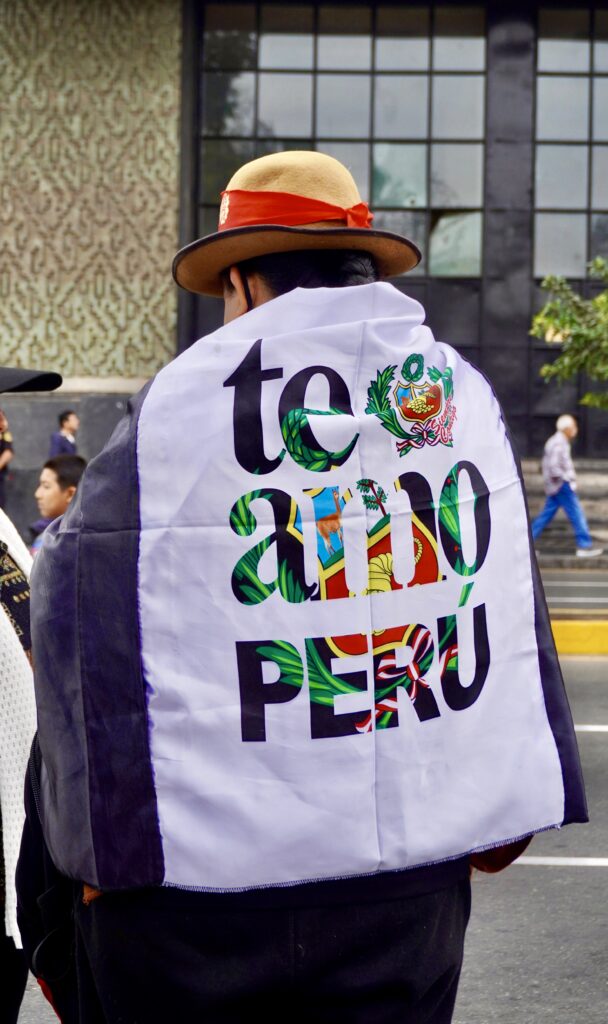

The 28 July commemorates the liberation of Peru from Spain. The following day, 29 July, celebrates the establishment of the Republic of Peru. Every building is decked out with red and white flags. For Peruvians, who kit themselves out in traditional dress or their national football shirt, it’s a day to be proud of their country.

This year, however, over 30,000 police officers are guarding the capital from the third Toma de Lima (‘Takeover of Lima’), a series of protests that reject power in the hands of the current Boluarte government.

‘For me, the worst is the Congress. At least Dina is doing what she can’, says Carlos Medina, a waiter in Plaza San Martín, in the heart of Lima, and one of the few forgiving members of the electorate. ‘They’re all in prison. Fujimori, Humala, Castillo’, he continues, naming recent Peruvian presidents. ‘Alan García committed suicide to avoid the slammer. That’s what Dina’s got to go by, corruption’, he says shrugging.

Meanwhile, fierce shouts of ‘Dina asesina, el pueblo te repudia’ (‘Dina, murderer, the people reject you’) boom through the square. Today, more than ever, Medina’s indifference is not reflected on the streets of Lima, capital of a country where 81.6 per cent disapprove Boluarte’s regime and 90.4 per cent reject the conservative-majority Congress.

Later in the morning, many protestors emanate peace, playing Andean music on the siku. Yet others come prepared with gas masks and helmets, chanting ‘Las calles son del pueblo y no de los corruptos’ (‘The streets belong to the people, not to the corrupt’) and ‘28 de julio, la patria está de duelo’ (‘28 July, our homeland is in mourning’).

Celebrations on the back burner: Lima in mourning

Along the Avenida Nicolás de Piérola, protesters can be seen carrying lit candles. Julia Rivera Huanmalías, who lives in Chorrillos, an hour away from the capital, says she and her sister have come to seek justice for victims who have died in protests. Since December 2022, at least 70 people have been killed, many of them due to police brutality.

‘Nobody’s even batted an eyelid at us. National press says we’re just a handful of rebels or criminals, but look’, she says pointing. As LAB follows her finger, what started off as a solemn morning begins to pick up the pace as hundreds file in with banners.

‘¡Dina asesina! ¡Dina asesina!’, the sharp chorus hits like a punch in the stomach. ‘She’s the one who’s responsible for it all’, sighs Rivera Huanmalías, gazing at the protestors’ ominous posters that depict the president covered in blood.

The Aymaran fight

‘Coast, Mountain, and Rainforest’, Javiana Marca Ticona, an Aymara lady from El Collao province in Puno, begins to speak firmly, naming Peru’s three principal regions. ‘We’re united today because we’re marginalized by the authorities’, she continues, explaining that the Aymaran fight has three objectives: a new constitution; closure of Congress; and Boluarte’s resignation.

According to Javiana, ‘We chose a rural teacher as leader [Pedro Castillo, president from July 2021 to December 2022]. He’s the one who represents us. He’s humble like us and does things for the people. Boluarte wants to sell our land to international companies. We’re the guardians of our own wealth and that’s not what we want’.

Aymara women and other Peruvian citizens call out corruption in Congress and violence in the streets. Many call for the President to be removed from office. Some ask for Castillo’s freedom. Independence Day demonstrations in Lima, Peru. Photos: Natasha Tinsley

The battle for dignified pensions

After a religious ceremony, President Boluarte arrives at the Government Palace to deliver the usual message to the nation at 11:00am. ‘Us workers go against Boluarte because she discriminates’, cries 73-year-old limeño Manuel Condori.

‘She’s given Congress employees a bonus of 10,000 soles (£2,170) a month yet kills the rest of us on ONP pensions, sparing just 300 soles (£65). It’s not like they’ve got no money. So where is it?’, he demands.

‘The fact she’s celebrating today makes me feel cheated. Who can live on 300 soles?’, Condori cries. ‘I’d like to ask Dina if she can’.

Poverty, hunger, and health

The most heartbreaking problem according to Lidia Carrero Diaz, a teacher from Cajamarca, is how many cases of anaemia there are at her school due to children’s poor nutrition. ‘For lunch they get horrible food because alternatives are just too expensive. The cheapest rice, the cheapest soup, the cheapest tuna. People are dying of hunger and prices only rise. Our institutions are rotting with corruption’.

Dr. Carlos Matos, one of 300 medical workers who took to the streets on 28 July, says employees known as ‘CAS-COVID’ are demanding to be legally recognised as ‘CAS’, a different type of contract ensuring more rights, such as food benefits and a higher salary.

‘In total there are about 1,500 of us’, says Dr. Matos, explaining how the law doesn’t recognise them for having started work during the pandemic. ‘They only recognise the former CAS staff, but forget we too were at the forefront of our country’s recovery’.

Strength and resilience: a glimpse at the future

As the morning comes to a close, LAB asks how this 28 July has compared to previous years. ‘Before we used to dance el huayno or la marinera in the streets. We’d eat and eat and eat’, says Rivera Huanmalías’ sister Yolanda, ‘This year there’s no excitement. Before we’d dress up and go to all sorts of cultural events or serenades in the Plaza de Armas – back when the square wasn’t closed to keep protesters out’.

‘This is what you’re seeing in Lima, but people are this riled up in every province of Peru’, affirms Julia Rivera Huanmalías, ‘Both the Executive and the Legislative Branch have to go. There has to be change. Without change there will be no justice. And without justice, the Peruvian people will not back down’.

‘Getting rid of Dina is only the starting point. We are seeking deep change.’ All photos: Natasha Tinsley