For over a year, Mexico has been battling the COVID-19 health emergency, which has led to over two million confirmed contagions and over 200,000 deaths, positioning it as the country with the third highest death toll worldwide. Whilst these statistics govern national headlines, another worrying, silent pandemic is currently unfolding. Violence against women, including femicides, has increased exponentially.

Statistics disclosed by the Mexican government reveal that 367 femicides were recorded between March and April 2020 alone, representing a 22.3 per cent increase relative to the same period in 2019. On average, 10 women die daily in Mexico. Just in April of last year, 11,610 emergency calls related to gender violence were recorded – 16 every hour. Yet despite these alarming statistics and the sensationalised press coverage of femicides, the federal government has made clear that femicides are not a priority on its national agenda.

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), has repeatedly emphasised that the systemic violence and killing of women is simply a symptom of the wretched neoliberal system he inherited from his conservative predecessors. He has also claimed that 90 per cent of the emergency calls to 911 – used by victims of gender violence in urgent need of help – are false, and that despite the pandemic, there is no observed increase in gendered violence.

The facts do not tally with the President’s declarations. His denial can be interpreted as a futile attempt to divert attention away from an issue which is deeply woven into Mexico’s misogynistic social fabric. By minimising the ‘hidden pandemic’, the President not only normalises violence against women, but also implicitly justifies policy decisions that undermine efforts to reduce it.

In July of 2020, the government approved a cut of 75 per cent from the budget of the National Institute of Women (INMUJERES), a protagonist in the defense of women’s rights. At the onset of the health emergency, 32 state-level attorney general offices were closed, impeding the due process of reported cases of gender violence and femicides. Perhaps the most worrying devlopment is that the 2021 budget plan does not protect programmes against gender violence from budget cuts that are part of COVID-19 austerity measures.

The intersectionality of this increasing violence

It is extremely concerning that AMLO denies the severity of gender violence and femicide at a time of severe budget cuts, especially considering the extreme forms of violence used in many femicides in Mexico. Notable cases are those of Fatima Aldrighetti – a seven-year-old girl who in February was picked up from school by a stranger and was found dead days later, exhibiting signs of sexual violence; and Ingrid Escamilla – a 24 year-old who was brutally assassinated and mutilated by her partner in Mexico City.

Although femicide is not a recent phenomenon – contrary to AMLO’s staunch belief in a causal link between neoliberalism and gender violence – the increasing level of arbitrary violence is symptomatic of the fact that abusers are often granted impunity by Mexico’s judicial system. The likelihood of perpetrators being brought to justice is undeniably low – regardless of the victim’s age, the pain inflicted, or the evidence found.

Nor does the law apply equally to all cases of gender violence. Women are granted different degrees of access to security as a public commodity depending on their identity. Certain factors which make up someone’s identity, like race, socio-economic status, accent and sexual orientation, play a key role in determining the kind of support a woman will receive.

According to a study conducted by the Autonomous University of Mexico and the National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Communities, the rate of growth of femicides is higher amongst indigenous communities.

Violence against indigenous women is particularly poignant in the mountainous area of the state of Guerrero where, according to the Center of Human Rights of the Mountain of Tlachinollan, there have been 20 femicides since the start of the pandemic. Importantly, the organisation asserts that municipal authorities have covered up and facilitated violence against women, refusing to conduct adequate investigations.

Socio-economic status also plays an important part. For example, a white, wealthy woman who reports a case of sexual violence is more likely to obtain justice as opposed to a poor morena. This dichotomy is indicative of the disturbing social construct that poor women are disposable, particularly because their families cannot afford lawyers and sustained resources to pressure the authorities to act.

A significant example is the killing of maquila workers in Northern Mexico – women from a low socio-economic strata who migrate from the south of the country in the pursuit of a quasi-American Dream, working in factories scattered alongside the US border in order to send money home to their families. In Ciudad Juárez, the epicentre of femicides in northern Mexico, over 900 women have been killed since 2010. Yet, 98 per cent of these crimes go unpunished.

Institutional impunity

With impunity deeply embedded in Mexico’s judicial and legislative system, gender violence does not get the attention it requires as a national issue. The more gender-based violence is ignored by the courts, the rarer it becomes for institutions working to protect women and assist victims to receive national budget allocation. This presents a huge loss for the financing of social and institutional infrastructure dedicated to assisting victims of gender violence.

Impunity is not only a result of chronic corruption, but also of the ambiguous and limited typification of ‘femicide’ in the Penal Code. Even though the General Law of Women’s Access to A Life Free of Violence establishes a common framework between federal and state governments to prevent and punish violence against women, the Law does not explicitly define what constitutes a femicide. This creates room for interpretation in the judicial system, which historically defends the integrity of the patriarchy.

Moreover, the Law stipulates that in order to categorise a murder as a femicide, there need to be relations of trust between the victim and the perpetrator. The fact cases like Fatima’s exhibited no links between the victim and the perpetrator and that plenty of maquila workers are exposed to sexual violence instigated by men they don’t know, means this typification creates a grey area conducive to a vicious cycle of impunity. Between January and June of 2017, 800 women were assassinated in 13 states in Mexico, and only 49 per cent of these cases were investigated as a femicide.

Due to a lack of government funding and planning, complaint centers have failed to adapt to the demands of the pandemic, creating a vacuum wherein victims are once again abandoned. In an Amnesty International study concerning the impact of the pandemic on law enforcement services in the State of Mexico, it was found that work overload, insufficient digitisation, unequal access to technology and the internet, and a lack of internal institutional coordination have all hampered efforts to mitigate the rise of domestic violence during the health crisis. According to an officer of the public ministry of the State of Mexico, “the index of domestic violence tripled” in the first few months of the lockdown, yet no efforts were made to recruit more personnel to respond to the emergency.

The Role of Civil Society

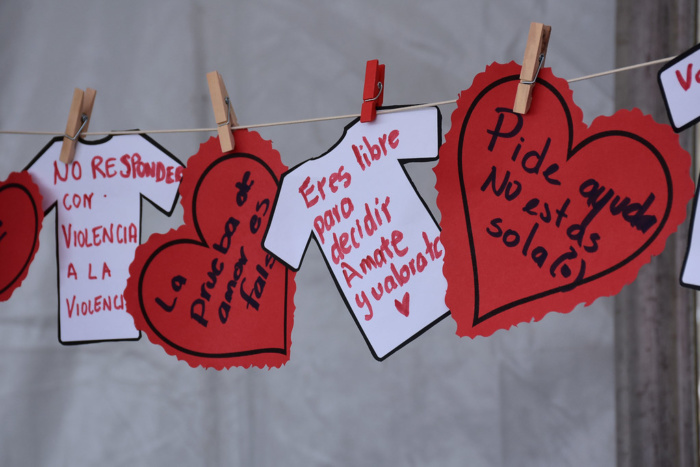

Despite the seemingly unstoppable spiral of gender violence in Mexico and the negligence of public authorities, there is cause for optimism – feminist civil society is unapologetically vociferous. Groups like the OCNF, Catholics for the Right to Choose, and the Witches of the Sea (Brujas del Mar) have openly condemned the prevalence of misogynistic violence, noting that governmental actions have been insufficient.

They condemn AMLO’s passive approach to gender violence, calling out his hypocrisy for continuously using his government’s gender parity as a red herring to divert attention away from his evident inability to recognise Mexico’s gender violence crisis.

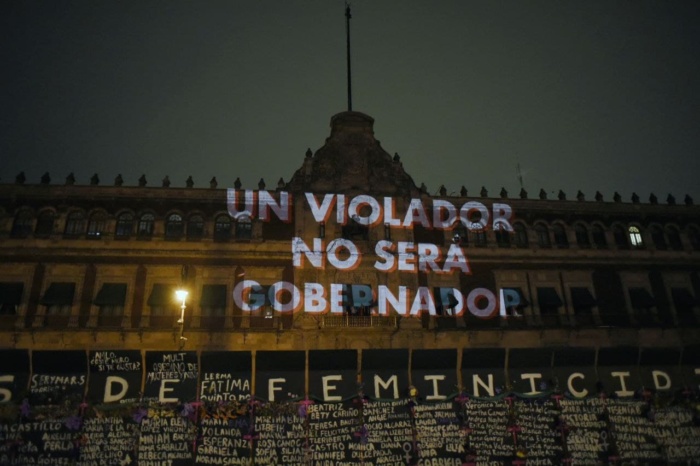

In an evocative protest staged on 26 March, images of 36 candidates who are running for state and municipal elections this July were displayed on the walls of the National Palace in Mexico City in order to expose them as perpetrators of sexual harassment and rape.

The continuous militancy of feminist groups plays more than a systematic role, however. It serves to awaken a society that has long grown accustomed to evident gender violence – and to indifference, complacency and impunity. By propagating a shared sense of indignation, the government is forced to pay attention, particularly in the midst of elections that have the potential to reconfigure the power of MORENA, the ruling party.

Amidst so much violence and a negligent administration, it is exceedingly difficult to remain optimistic. The State has a constitutionally enshrined duty to protect its citizens. So what, then, is the answer for half of the population who feels abandoned and imperiled by a precarious justice system that fails to even properly categorise gender violence, let alone to halt torturous abuse?

The reality is that at present, the State cannot provide an answer. But civil society can – through a network of tireless women who are surmounting expectations and orchestrating a concerted effort to finally prioritise gender violence in the national agenda.

Main image: Screenshot from Norma Andrade: justicia para los feminicidios en Ciudad Juárez (YouTube).